The immediate fallout of dismantling the protective provisions in August 2019 is that outside entrepreneurs have become an intermediary between the government and the local businessman. This is showing up in a sharp spike in the prices of construction materials, be it sand, bricks or bajri. Added to this has been an increase in the cost of labour making it all the more difficult for the average middle class local to own a dwelling, reports Khalid Bashir Gura

Zahid Ahmad, 40, a resident of old city Srinagar, planned to construct his house. He thought of moving out of the congested old house where he lived with his elder siblings. A year later, his dream of having his own house is nowhere near realization as the escalation in construction material costs has made it prohibitively expensive to do so.

Ahmad, a Kashmir handicrafts dealer, was living in South India for the past two decades. “Constructing a house was not that costly earlier as official impediments and procedures were less,” Ahmad said as he started realizing the cost of constructing a house. At the very start, he had to cough up two lakh rupees as stamp duty for the land he acquired. “I had no problem with legal procedures but when the municipality and police questioned the legal construction that took me by surprise.”

Finally, he said, he did what Romans do – greased palms of different officials at different levels. As he moved towards construction, Ahmad was shocked by the sudden soaring of construction material costs.

“The extra labour costs and sudden soaring of prices are back-breaking,” Ahmad said. “I had never estimated this worst-case scenario,” he said.

Ahmad said he spent many days enquiring rates from different kilns from South to Central Kashmir but was disillusioned. “I don’t know if there is any fixed rate. Initially, when I chalked out the budget I had estimated the cost of a truckload of bricks for Rs 21000 and sand Rs 6000,” said Ahmad. He now pays Rs 27000 for a truckload of bricks and Rs 10500 -13000 for a truckload of sand. The labour cost to ferry the bricks to the site of construction adds Rs 2500 per truckload.

“They say costs depend on the grades and varieties,” said Ahmad who is still uncertain if he is getting the best quality for the amount he pays. His savings have exhausted and he is forced to sell some assets like gold. “I cannot afford to incur the debt of bank which is also reluctant to grant a housing loan.”

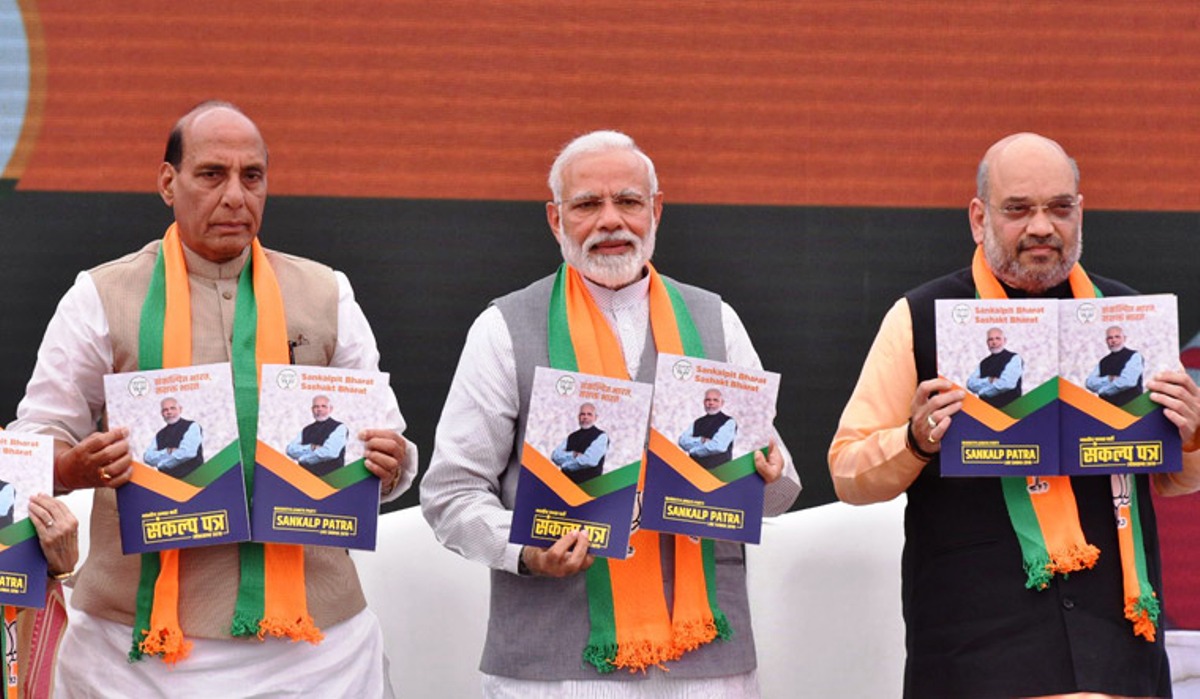

2019 Mess

The successive hurdles he faced in constructing his house were reading down of Article 370 and 35A in August 2009, followed by crippling clampdown and Covid-19 lockdown since March.

Following the revocation of Article 370, all the non-local labourers left Kashmir which brought government and private construction to a halt. It froze the development story, literally and proverbially.

As a result, the production of bricks in kilns was reduced drastically. Later, the Covid-19 lockdown delayed the return of the non-local skilled kiln labour force. Now more than a year after Article 370 move, Ahmad finds no respite as the prices of construction material continue to rise.

Own House

Kashmir’s love for modern and new houses is making them pay from their nose. “Earlier most houses were built by using mud and wood but now the trend has changed,” Ahmad said. Kashmiris spend painstakingly hoarded lifetime earnings on building houses, most of them three-storey tall, with painted tin roofs and large windows. Though the vertical housing is a concept that has been adopted the world over, it is yet to get some sort of acceptability in Kashmir. Every family needs a separate house, a lawn and once a boy or a girl gets married, “my house” is the top priority.

That is how Ahmad is struggling with a basic structure in his limited budget. The sudden soaring of the construction material is something that is playing a major crisis for the real-estate sector.

Expensive Bricks

Abid Malik, a brick kiln owner, agrees that the rates have skyrocketed since last year: “Article 370 move triggered a labour crisis and production was reduced which resulted in high prices,” Malik said. “These started stabilising once the labour returned.” In order to interrupt in reducing the brick costs, the government, at the peak of the Covid-19 lockdown somehow managed to get more than 11000 skilled labour forces from different states so that the brick sector returns to some sort of normality. Even the brick kiln owners resorted to what was said the “smuggling” of labour – managing re-entry of the labour bypassing the Covid-19 protocol. Deputy Commissioner Srinagar, in one raid, traced 200 “smuggled” workers and fined the “smugglers” heavily.

Initially, real estate activities had nose-dived. The ongoing construction work stopped in August and did not pick up till winter. It resumed some activity early April but the Covid-19played the spoilsport.

Stressed Lot

Not so far away from Ahmad’s house in the old city, Bashir Ahmad Guzar, 45, lives in his rented accommodation at Khanyar. Guzar, a papier-mache artist since 1992 is also constructing his house at Nowpora after the Covid-19 lockdown was eased in mid-August.

At his rented room, the books of his three children are scattered across the congested room as each of them is preoccupied with phones and books. The room has other belongings stacked up against walls. According to Guzar he has been spending the sale money from his previous old houses in the construction of a new house, education of three children and in feeding his family.

“As the business slumped year after year, in 2016, I was forced to give a thought of selling my old house in Khanyar to save some money to change the profession,” admits Guzar, who afterwards bought an old house in congested Rainawari in the same old city, Srinagar but sold it again.

As he could not revive his old profession, the papier-mâché artist struggled to start a new venture due to crippling lockdowns. This added to his financial woes.

Even though Guzar lives in a nuclear family, with his wife and three children, constructing the house has been difficult with the rising prices of construction material in the last few months. “I live in a rented house. So I am forced to construct a new house, no matter what,” he said. But the prohibitive escalation in costs is draining his budget.

“I have to pay Rs 32000 for the same truckload that I could have bought for Rs 21000, a year ago,” Guzar said. “The extra labour charges to ferry bricks to the construction site are Rs 2500. The sand that I had expected to buy at Rs 6000- 7000 now costs Rs 10000-13000.”

As he is worried by the impact of the soaring prices on his budget and lack of work and income, Guzar revealed that contrary to his expectation of prices slumping after the Covid-19 lockdown, the rates have only further increased. “My budget is the same but the inflation is showing upward spike,” Guzar said.

The family needs to leave the rented accommodation soon as the rent is further reducing his savings. “I have to pay Rs 5000 per month for two rooms and we have been living in it for more than a year now,” said Guzar. Even though the construction material continues to be sold at inflated prices, for now, Ahmad wants to see himself in his new house before winter.

Kiln Story

While Ahmad and Guzar blame the brick kiln owners and government for rising prices Zahoor Ahmad Malik, the president of Brick Kilns Owners Association (BKOA), differs.

Malik said that the “labourers who came during the pandemic and demanded extra alary to restart work.” The less production led to increases in rates, he added.

According to Malik, the brick kilns produce bricks between June to November in Kashmir.

“After that, the labourers move to other parts of India where they work till May-June,” he said. “This year the production was less due to delay. The production began late because of the shortage of workers”.

Malik said there should have been a fixed rate for bricks at Rs 8000 per 1000 bricks aggregating to Rs 24000 for a truckload of bricks.

Sand Crisis

The people at the receiving end of exorbitant construction material prices blame the government. Officially 150 square feet of sand should cost Rs 3000 but it costs us more than Rs 10000. Similarly, there is a huge variation in the price of bricks.

Earlier, in 2015, the administration fixed rates of A-grade bricks at Rs 18000 per 3000 bricks, including loading and unloading costs. Later, after the repeal of Article 370, the UT government revised the fixed-rate after five years in August 2020.

“The cost now has been fixed at Rs 7000 rupees per 1000 bricks,” he said which means a truckload of bricks on the ground should cost Rs 21000.

While reasons for soaring prices may have been a shortage of labourers, less production and successive lockdowns but for common man constructing a house is becoming a nightmare.

Online Auctioning

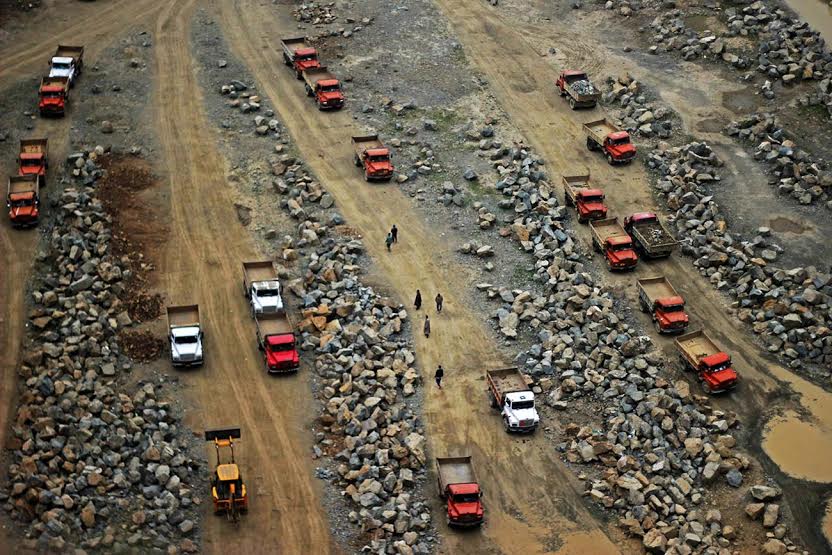

Similarly like bricks, the price of a truckload of sand has also spiked in the past few months. One of the sand dealers, Waheed Ahmed in Srinagar blames the allocation of mining contracts to non-locals for soaring prices. Until the 2016 riverbed mining in the former state was done by local miners over small spaces through short-term royalty contracts but the new rules after Article 370 mandated authorities hold auctions for minor mineral blocks, measuring not less than five hectares in area, with leases granted for a minimum of five years. Interestingly, this entire process of inviting miners was done online at a time when Kashmir was under communication gag. All the miners from north Indian plains applied and took the contracts.

The new rules also made it compulsory for miners to obtain environmental clearances before starting mining operations. “Initially the sand would cost Rs 5000-6000 now it costs more than Rs 10000. The sand extractors are giving us sand at the cost of Rs 8000 per truckload and we sell it at Rs 9500, which includes the transportation charge, bank and other charges,” said Ahmed.

According to Malik, no one in Kashmir has environmental clearance certificate demanded by Geology and Mining department. “It is all happening illegally and the authorities are not so keen to look towards this aberration.”

“We are requesting the officials to amend the stringent rules in new laws till we adapt,” he said. “The construction material is a source of livelihood for a lot of people; local to non-local. The non-local labourers working in brick kilns, transporters, labourers, masons, carpenters, sand extractors, and others are interlinked in the construction business”.

Trucker Issues

Aijaz Ahmad, a Srinagar resident, who owns a tipper, is constructing the first floor of the house. According to him, he ferries sand of superior quality from the South Kashmir at the cost of Rs 10000 and bricks at the cost of Rs 24000 from the kiln itself.

“If I had to sell the same sand to a customer I would charge him around Rs 15000,” he said, adding that the rates vary according to quality also.

The gravel, he continued, costs at Rs 6500 at the crusher and after adding transport charges the customer will get it at Rs 8000-8500.

Ahmad and Guzar, yearn to shift to their new houses soon. “I fear if my children will be able to construct their own houses in future given the slumping of the economy and the rising inflation” the duo said with a deep sense of foreboding.

Illegal Extractions

As the system paved way for the entry non-locals into the mining activities, there were critical issues that were bypassed, insiders in the sector suggest. With the huge market appetite for the material, authorities at various places permitted them to start mining without mandatory clearances.

Muhammad Maqbool Parray, President Himalayan Quarry and Tipper Association said that the system of the mafia in mineral extractions has been institutionalized to benefit people non-natives. “A truckload of the quarry before the ban would cost Rs 2000-2500 in Nowgam, in Srinagar periphery. Now it costs Rs 4500-5000.”

As the new rules have made it mandatory for miners to obtain environmental clearances before starting mining operations, local contractors say they are discriminated as outside contractors are allowed to work smoothly despite lack of producing prerequisite documents.

Earlier, following the ban on quarrying operations, quarry holders of Athwajan and Pantha Chowk Srinagar had protested blaming the government for snatching their livelihood. “If the Geology and Mining department would lease contracts and take a royalty, the prices would automatically come down. But they are intentionally allowing the mafia system to prevail,” Parray alleged.

Two years ago, the government had started a process to shift the quarry holders to Shaleguph and Zewan but were not allowed to work even there by the people already working there.

“We used to pay royalty towards Geology and Mining department and used to get permission for extractions of stones for sale,” Parray said. “Now the department is not issuing clearances as it has been given to outside contractors.” He indicated as if they are Kashmir economy’s new outlaws who cannot be seen working in the day. He alleged that if they manage some material, the trucks are being seized and hugely fined.

The rates of quarry vary and have now doubled. “Earlier the Srinagar city would get a truckload of stone quarry for rupees Rs 2100 to 2200 and now the same costs above Rs 5000,” Farooq Ahmad, another quarry holder said.

Bajri Tensions

Muhammad Shaban one of the owners of stone crusher and manufacturer of bajrisaid that he has to pay the contractor of Punjab almost Rs 600 for half a truckload of boulders. With loading and labour charges, it reaches his crusher at Rs 1200. The one cubic feet of bajri now costs Rs 25 and it is sold to a customer at Rs 5000, a truckload against Rs 2800 earlier.

Earlier Shaban had to pay a royalty of Rs 30000 per month towards the mining department but now the one day cost may shoot up to Rs 1 lakh.

Political parties are aware of the crisis but feel helpless. “Most of the auction tenders were allocated when Kashmir was under communication blackout. It is a myth that tenders have been allocated,” PDPs Waheed Parra said. “No one has received environmental clearance and despite that mining and extraction is being allowed at higher prices to fill in the pockets of outsiders. The crux of such policies by the government is to dis-empower us.” He said the same “loot” is taking place in Jammu. “The stones cheaply available have been turned into diamonds for locals.”

Stressed Futures

Given the changes that are taking place in the overall systems and the processes, the real estate in Srinagar is going to get unaffordable in immediate future. Right now, the pressures on the land resources are increasing. The opening of the land resources for purchase by the non-natives – officials say it is less than 10 per cent, and the process of retrieving the land taken by the people under Roshni scheme is expected to reduce the availability of land for sale and purchase for housing. Even in villages and the peripheral towns, a process of retrieving the state land has started.

Now the Registration of land is a full-fledged department and it will ensure that every inch of land traded in Jammu and Kashmir must pay every penny of stamp duty. This will add up to the overall costs in the coming days. In Kashmir, official sources said the stamp duty fall is witnessed because the purchasing capacity has gone down at a time when cost are slowly but steadily appreciating. Against Rs 130 crore stamp duty collections in 2019-20, sources said the collections so far have been around Rs 60 crore only.

If the prices remained as they are, Srinagar will be looking towards a situation where the housing will emerge a serious challenge, especially for the main Srinagar city where most of the urban poor live.

“After Article 370 was abrogated there has been a serious labour supply crisis which points to how even before August 5, 2019, there was an influx of and a dependence on outside labour. The labour market, the money markets, the commodity markets – all were completely integrated,” economist and former minister Dr Haseeb Drabu said. “Only the land market was regulated. Now that too has been opened up. It will have long term consequences on land as an investment class, land for housing and land for the enterprise.”

That situation is expected to hurt the interests of the urban population especially from the lower middle and the lower segments of society where the housing requirements are desperate and affordability is a serious concern.