With his impressive research ‘The Syncretic Traditions of Islamic Religious Architecture of Kashmir’ published by Rutledge early this year, Dr Hakim Sameer Hamdani, currently Design Director at the INTACH Kashmir, is flying for his post-doc to the USA. He spoke to Kashmir Life on various facets of Kashmir’s architecture between the rise of the Muslim period and the fall of Sikh rule

KASHMIR LIFE (KL): Before the Muslim culture started influencing it, how was the architecture in pre-Islamic Kashmir?

HAKIM SAMEER HAMDANI (HSH): It is indeed vital to know ‘what was’ before we study ‘what is’. Unfortunately, our understanding of Muslim material culture in Kashmir, especially its architecture is based on narratives that were governed by the ‘colonial project’. Written in the early twentieth century, mostly by British art historians they reflect the prejudices of orientalists, who see an imagined divide – break in political, cultural and art history of the region between a Buddhist, a Hindu and a Muslim past, separate and contained within themselves. As a part of this ‘colonial project’, the Islamic architecture of Kashmir is seen as being built upon destroyed remains of Hindu sites.

But if we see Kashmiri religious architecture be it Buddhist, Hindu or Muslim in nature we see a continuity of form. And more importantly totally distinct from what we see in the rest of South Asia.

An important reason for the evolution of this distinct style is the geography of the land. Kashmir is a mountainous region linked to important cultural routes on its north and west. Yet, at critical times the land could also isolate itself from what was happening outside and this isolation had shaped Kashmir in a major way. We need to remember that Kashmir was conquered by many powerful empires from the West as well as the South, which resulted in the introduction of new ideas and designs. But, then it is within the fold of its geography that Kashmir accepts, rejects and then translates these external ideas and influences into a new artistic grammar, which is unique to this land. Thus we have Hellenic, Gupta as well as Tibetan influences on the pre-Muslim architecture of the region, to name just a few major influences. And in turn in the seventh and ninth century, a Kashmiri architectural style evolves, which would leave its traces and influences on much of the surrounding Himalayan hill states.

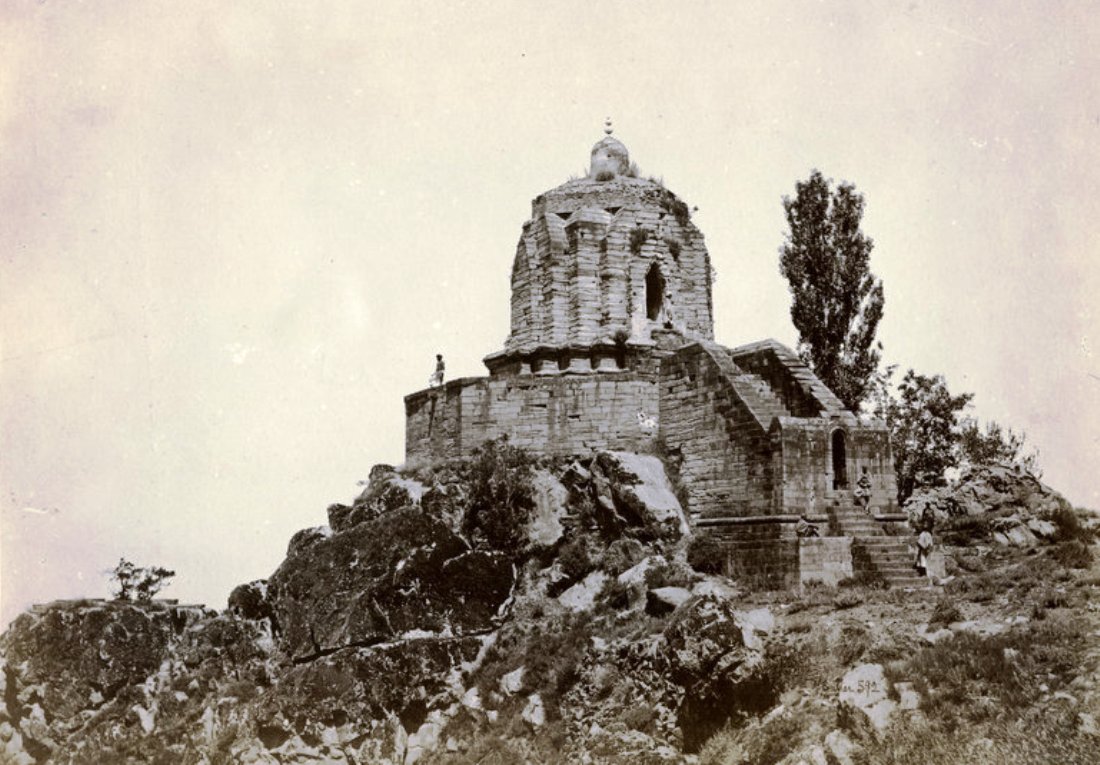

Today if we look at the medieval stone temples of Kashmir you find their volume, articulation and overall architectural composition so very different from what we normally see in the rest of mainland India – whether it be what we term as the North Indian temples or the South Indian temples. Even the way sculptures are carved on the temple walls, their overall contribution to the visuals, it just so different between what is happening in Kashmir and what is happening south of Pir Panajal.

KL: Most of the Kashmiri architecture after the Islamic period was wood-based, but the medieval temples of Kashmir dating back to the Hindu period used stone, why?

HSH: It depends on the local raw materials present in the area. Kashmir is rich in stones, especially limestone which we call Devri Kani (said to be derived from ‘dev kani’, Stone of the Gods) and the resources to make these temples were in abundance.

Again we need to understand that building in stone, symbolizes not only power, and durability but also the munificence of the patron responsible for these constructions. In building in stone, the kings of medieval Kashmir were not only creating public places of worship but also propagating and preserving their image: as powerful and pious patrons. Also, historically we find textual references to temples and viharas constructed in the vernacular wooden style, but due to the perishability of wood as a material, nothing survives from the pre-Sultanate period, in Kashmir. Still examples of the Kashmiri style of wooden architecture are to be found in Alchi (Ladakh) and Udhumpur (Himachal).

But, yes you are right in saying that wood as a building material did not find much favour in the medieval temple architecture of Kashmir, especially in monumental architecture.

KL: Some historians believe that before the spread of Islam in Kashmir in a period when Muslims were making inroads into the subcontinent, Kashmir was a target of fortune hunters. Is there any way to check the veracity of these claims in archaeological studies?

HSH: By, fortune hunters, I believe they are referring to soldiers of fortunes, but then we can also add traders to this category. Historically, Kashmir has at crucial periods in its history remained closed to outsiders, but then located on a branch of Silk road (the erstwhile Salt route), it has also maintained a cultural and political connection to lands to its north, west as well as south, So we have al-Beruni at the time of Ghaznavid invasion of South Asia writing about Kashmir as ‘a locked country’ were virtually no outsider was allowed to enter the country. But, then he does add that they allow foreigners know to them personally to enter. But the ban was not for too long – we find the presence of non-native Tursukas in Kahlhans narrative.

Also, we have these interesting early references to the Muslim presence in Kashmir during the Hindu period in Arab sources. Kitab-al Ajaib speaks about how an Arab from the Abbasid court was deputed to Kashmir, to teach the king about Quran, and as the Kitab would have it, this native Kashmiri Hindu king converted to Islam though he hid it from his courtiers. Also, in Usul Kafi we find reference to the arrival of a Kashmiri deputation in Balkh who converted to Islam and then proceeded to Baghdad. Aside from that, we have interesting references from Indian texts, such as Chachnama.

But to see the material evidence of this Muslim presence before the fourteenth century we need to go back to Leh again, where in the murals at Sumstek temple, which is roughly dated tenth or eleventh century, where we find, clear indications of Muslim influence – whether it be in the costumes depicted, the headgear, or the tariz embroidery on the robe. It is worthwhile to remember that though located in Ladakh, the temple was constructed by Kashmiri artisans who in their artwork are basically depicting, something with which they were familiar. So the possibility is that either the artists were Muslim, or they were depicting Muslimness in terms of costumes etc which they had witnessed themselves.

KL: Which structure would you consider as the best representative of Islamic architecture in Kashmir?

HSH: Well, actually there has been a lot of debate going on in the academia suggesting that the term ‘Islamic architecture’ itself is a colonial construct- hence the increasing preference to use ‘Islamicate’ rather than ‘Islamic’.

However, in terms of Muslim religious architecture, there are many examples of old mosques, Khanqahs, shrines constructed during the Sultanate period. In my book, I have described them in great detail – both in terms of their architecture as well as their political and cultural context. Muslim religious architecture of Kashmir is an interesting and unique addition to not only South Asian architecture but, if I may use the term wider world of Islamic Architecture. Unfortunately but for a passing reference to a few monuments in this architectural genre, this style has remained unexplored. Personally, my favourite remains the Mir Masjid at Pampore.

KL: Out of all the Islamic Architecture present in Kashmir, be it mosques or shrines, which one would you say is the oldest?

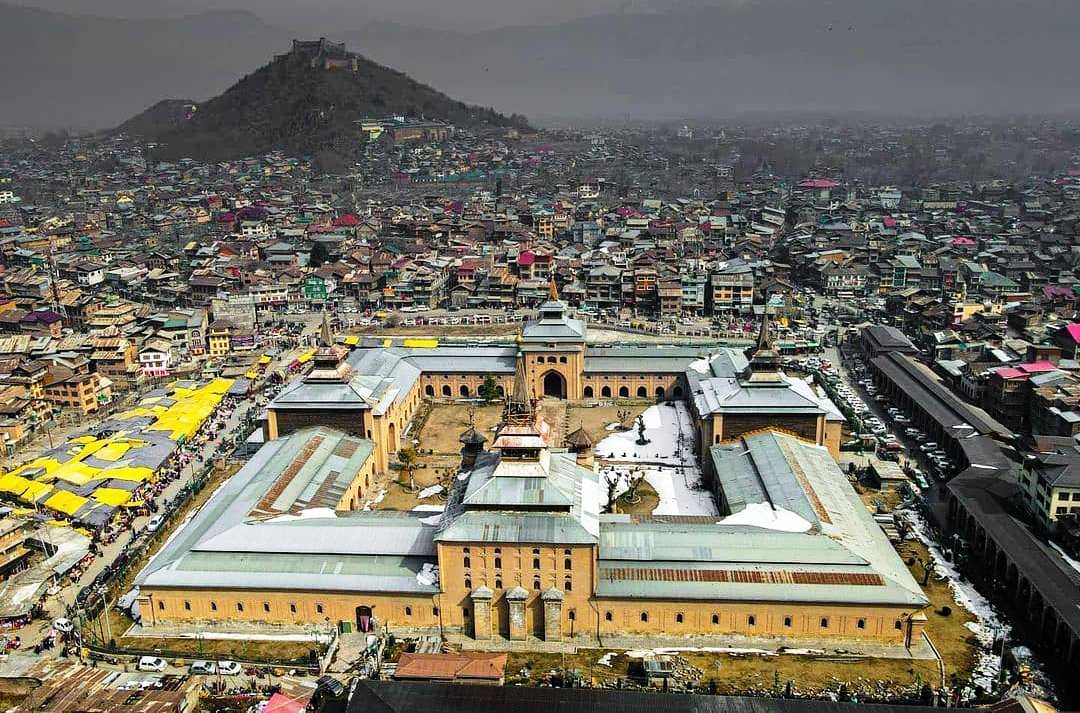

HSH: The oldest archaeological trace that we have is of Rinchinas mosque at Aali Kadal, the oldest building surviving almost in totality is Mir Masjid at Pampore. But in terms of their immediate cultural relevance, I would say that the most important is the typology of Khanqahs. Historically, Kashmiri mosques have paled in terms of both their size and their importance in society as compared to Khanqahs. The sole exception to this phenomenon is in the genre of Friday mosques – the Jamia’s. The prominence of Jamia Masjid’s has been there since the beginning – from the days of the early Islamic empires, as that one big congregational space made to accommodate a city, always filled up during various festivals or important prayers such as the Friday prayers.

Also, as I mentioned earlier, the resources spent on Khanqahs by the people and the court were more than what was spent on a mosque. Most of the Khanqahs were well endowed with revenue of villages etc. They were liberally patronised by sultans, Amirs, merchants as well the common people. That is an important factor that one can see even in this era as well, though in the absence of sultans it is community patronage that has stepped in.

KL: Were our Khanqah’s our Darasgah (school) initially?

HSH: Khanqahs were always Darasgas. If we look at Arab lands – say Syria, Maghrib, they call it Rabbat; these are small rooms for prayers, zikr etc. As you move towards Iran or as we say the Persianate world, the term Khanqah comes into prominence, which consists of all the Islamic activities and teachings. Its serves as a place for prayers, zikr, eating, solitary penances (chilla) as well in many cases also adding as a shrine.

In newly established Muslim lands, such as Kashmir in the fourteenth and fifteenth century, Khanqah was the seat from which non-Muslims would be introduced and converted to Islam by Sufis.

In Kashmir, we find Khanqah and the silslas linked to it was very Shariya oriented, though later on their way of functioning acquired local colour and also temperament. These khanqahs also left their mark not only on the built but cultural landscape. For example, the term Chillai Kalaan, which we use for the 40-day severe winter owes its origin to the Sufi practice of greater retreat for 40 days that would take place in winter, when sufis would go in chilla (seclusion). Then we have also the linkages between Sufi Shaykhs and crafts etc.

Aside from that, these Khanqahs provided food and shelter for the people during turmoil or calamity, so they functioned as historical spaces for the dissimulation of religious knowledge: a shelter, a mosque, a school, public kitchen and a shrine as well.

KL: In your book, you’ve covered the history of Islam in Kashmir from the Sultanates to the Sikh rule, what was the status of architecture when Islam started spreading in Kashmir?

HSH: The narrative which is circulating around these days is of a past as we would want it to be rather than the past as it was. If Muslim rule in Kashmir marks an antagonistic relationship between the components of Kashmiri society, Hindus and the Muslims then history will tell us so and architecture will witness it. As I have explained in the book, the Islamic religious architecture of Kashmir has critically and creatively engaged with the historical traditions and the forms of Buddhist and Hindu architecture while simultaneously articulating a unique Islamic identity and material culture.

For example, in my book, I have also written that when the Delhi Sultanate was formed, one of the first acts of the sultans was to construct Quat-ul-Islam Masjid and then Qutub Minar to celebrate the introduction of Islam in Delhi, and its victory.

But this trend never came to Kashmir. The Muslims in Kashmir sought to assimilate with the existing Kashmiri society, instead of claiming to be superior. From an architectural point of view, if we want to demonstrate differences, you will seek a competing architectural vocabulary. Also, scale matters. If a temple was made 10 stories high, a mosque would subsequently be made 20 stories high to demonstrate the hierarchy of dominance through scale. But as I said, this is not how the Muslim religious architecture of Kashmir evolved.

KL: Which are the oldest Islamic heritage sites in Kashmir of the Sultanate era?

HSH: There are two mosques, one is in Pampore, however mostly dismantled, but some remains are there. There is Rinchin Shah Masjid in Rinchinpora which is also mainly in ruins. There are also many sites you can actually see throughout the city and also outside in towns and rural landscape, big and small which retain their original historical character to varying degrees.

But then unfortunately we have lost a major part of our built heritage from the Sultanate period to floods, fires and man-made disasters. Even the iconic Jamia Masjid of Srinagar has been rebuilt so many times, the present construction being a Mughal reconstruction.

KL: What are your thoughts on the Mughal architecture in Kashmir?

HSH: Mughals spent an enormous amount of money to develop their architecture in Kashmir. If you look at it, they mainly came to Kashmir to escape from the heat of the Indian plains and enjoy their terrestrial paradise; their bagh, their Firdous. They have celebrated the land but remained silent about the Kashmiri people to the point where you find the natives missing from their idea of Firdous. Kashmiri people are marginalised to the background in the idyllic miniature of paradise that the Mughals created for themselves here.

Since they viewed Kashmir as a paradise, they created sites, which represented their image of heaven on earth through their architecture and celebrated it in their poetry. Apart from the gardens, they also built mosques like the Mulla Shah Masjid and another mosque in Ganderbal, all representing the metaphor of heaven.

Overall, Mughal Architecture in Kashmir represents and celebrates the Mughal sense of aesthetes, ignoring in totality how Kashmiri Muslims had been building their mosques, Khanqahs and shrines before the transfer of Kashmir to the Delhi durbar.

KL: Although having the same mentality, was the Afghan rule different from the Mughals?

HSH: Basically Afghan rule emerged from the collapse of Imperial Mughal authority in North India. Obviously, the Afghans were not as resourceful as the Mughals. Also, they imbibed a certain provincial outlook.

As opposed to Mughal constructions, the architecture under Afghans shows both a constrained artistic vision as well as depleted resources. A fine example of this is a comparison between Mughal and Afghan construction at Naagar Nagar. The lower part of Naagar Nagar fortification was undertaken by the Mughals and the upper portion was done by the Afghans. The sturdiness of Mughal construction is missing in the Afghan fortification. By looking at these two constructions anybody can tell that the Mughals wanted to live through their architecture, to leave their mark on history, enshrine their memory through their architecture as compared to the Afghans whose concern was limited to fulfilment of an immediate functional need.

KL: Your book concludes with the Sikh era. What happens to Islamic religious architecture in that era?

HSH: If in comparison to the Mughals, Afghan architecture pales into insignificance, architecture under Sikhs shows a further decay, especially in terms of the motifs and design refinement. Also, rather than the court, it is the community, which is offering patronage for the repair or limited construction of Muslim religious sites. Traders, especially shawl traders figure prominently as agents of patronage.

(Sarmad Dev processed this detailed interview)