When Kashmir’s despots pushed women into prostitution to improve their tax kitty, a barber sacrificed almost everything in his crusade against the flesh trade. After paying huge personal costs, he finally managed a ban. In the first-ever detailed narrative on the life and times of Mohammad Sultan Hajam, historian Khalid Bashir Ahmad offers stunning details of Kashmir’s one-man army against the exploitation of women, a malady that even clergy and popular leadership avoided addressing

One of the many awful aspects of the Dogra autocracy (1846–1947) was its earning revenue from the flesh trade. Prostitution was officially permitted, and encouraged and was not a punishable offence in the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir. (see, Dar, Shiraz Ahmad, Shah Younus Rashid: Prostitution, Traffic in Women and the Politics of Dogra Raj: The Case of Kashmir Valley (1846–1947), Journal of Society in Kashmir) The official patronage enjoyed by women traffickers and brothel-keepers could be gauged from the fact that in 1880, up to 25 per cent of the Government revenue came from taxes levied on the flesh trade. The sale of a young girl to a brothel-keeper for a sum of Rs 100 to Rs 200 was “recognized and recorded on stamped paper” (Henvey’s Revised Note on the Famine in Kashmir, 1883, Foreign Department, Secret -E, March/1883, File №86, p 1, National Archives of India) even as the regime forced women to enter the market-space of prostitution. (ibid)

Arthur Brinckman, a missionary in Kashmir during the rule of Ranbir Singh (1830–1885), gives an idea of the special treatment sex workers enjoyed at the official level. According to him, while the poor peasants were forbidden to bring their supplies to the English visitors for sale the women of improper character were allowed to come freely, because they were all tax-payers to the Maharaja. (Brinckman, Arthur, The Wrongs of Kashmir, p 18) Not only did the Government earn from the flesh trade but at the death of a prostitute, the wealth gathered by her during her infamous life also reverted to the ruler. The Government did not spend on the well-being of the exploited women even a fraction of the money it earned from them.

The State as a whole presented a painful story with Jammu, the native land of the ruling dynasty, being no exception. In 1922, the residents of Reasi petitioned Raja Hari Singh who became the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir two years later, that “abduction, kidnapping and enticing away their womenfolk was the greatest misfortune from which they were being ruined both socially and economically.” (File No 459, Subject: Traffic in Women, Accession Regs. No. Misc/4293, Head: Municipality, Year 1986–87 Samvat., State Archives Repository, Kashmir). The then Chief Secretary, GEC Wakefield, who later became Hari Singh’s Prime Minister, wrote to the Law Member of the Council that “the reprehensive practice was most common and women of the State were sold like animals.” (ibid). The Tribune, Lahore wrote about the huge proportions of the kidnapping of women and trafficking in them had assumed in Jammu and Kashmir. (The Tribune, Lahore dated 13 March 1929). The weekly Ranbir, Jammu offered its columns for writers seeking eradication of the evil and newspapers of Punjab also highlighted the evil practice. (File No 459, Subject: Traffic in Women, Accession Regs. No. Misc/4293, Head: Municipality, Year 1986–87 Samvat, State Archives Repository, Kashmir).

The Dogra Sabha Jammu too chipped in by offering suggestions and proposals to rid the society of the menace. In Samvat 1983 (1926/27 AD), the Sabha was warned by its President, Pandit Chhota Lal: “It is necessary that I should let you [know] what I am aware of regarding traffic in women. I live outside the State. Many women of our places are enticed away by sinful and scheming persons to neighbouring provinces where they are sold.” (Lal, Jiwan, Traffic in Women for Immoral Purposes, File No 459, Subject: Traffic in Women, Accession Regs. No. Misc/4293, Head: Municipality, Year 1986–87 Samvat, State Archives Repository, Jammu). The magnitude of the problem could be understood by an official report of 1929 according to which there were 68 houses of ill-repute, nearly all run by women, under the jurisdiction of Police Station Jammu City. (File No. AR 4174 of 1958, Abduction of Women from the Kashmir State into British Territory for the Purpose of Prostitution, Police Minister’s Office, State Repository Srinagar).

The Glancy Commission appointed by Maharaja Hari Singh to look into the grievances of his Muslim subjects following the 13 July 1931 carnage at the Srinagar Central Jail, also dealt with the rising instances of women trafficking in Jammu Province. The Commission’s report presented a dismal picture of flesh trade in Jammu. An excerpt:

“This nefarious enterprise, known as Bardafaroshi [flesh trade], has been for many years the subject of grave concern in various parts of the Jammu Province where an organized business in abducting women and girls and removing them beyond the limits of the State has been conducted.” (Report of the Commission appointed under the Orders of His Highness Maharaja Bahadur dated the 12th November 1931 to enquire into Grievances and Complaints, Chapter 6, p 47.)

As regards Kashmir, the situation was appalling, to say the least. Lieutenant Robert Thorp, a British Indian Army officer, who visited the Valley during the reign of Ranbir Singh and wrote articles on Kashmir, posthumously published as a book titled, Cashmere Misgovernment, notes that the sale of young girls to established houses of ill-fame “is both protected and encouraged by the Government and helps to swell that part of his revenue which the Maharajah derives from the wages of prostitution.” (Thorp, Robert, Cashmere Misgovernment, p 48–49) F Henvey, British Officer on Special Duty in Kashmir, observed that “there can be no doubt that prostitution and the traffic in children for immoral purposes have, like everything else in Kashmir, been made to contribute towards the Maharaja’s income.” (Henvey’s Revised Note on the Famine in Kashmir, 1883, Foreign Department, Secret -E, March/1883, File No 86, p 2, National Archives of India). Following some adverse newspaper comments on this sorry state of affairs, Ranbir Singh ordered that the tax recovered from prostitutes be “discontinued for the present.” (ibid). The Government charged one hundred Chilki rupees to issue a licence for the purchase of a girl for prostitution and additional payment was made when the unfortunate victim entered upon the miserable career. The ill-fated women were legally forbidden from marrying and returning to normal life. If some woman tried to run away with a man of her choice she was seized and forced back into the life of sin. (Thorp, Robert, Cashmere Misgovernment, p 50) In 1880, there were over eighteen thousand registered prostitutes in Kashmir province, who paid taxes from their income to the Government (Henvey’s Revised Note on the Famine in Kashmir, 1883, Foreign Department, Secret -E, March/1883, File No 86, p 17, National Archives of India), including 250–300 in Srinagar. (Wani, Mudasir Ahmad, Dogra Rule and the Marginalisation of Women in Kashmir, International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT), Vol. 9, Issue 1, January 2021) The two most infamous brothels located at Tashwan and Maisuma in Srinagar were run by a non-Muslim local usurer named Sone Buhur. He trafficked women from different parts of the Valley. (Akhtar, Bashir, Suble Naevid (Subhan Hajam), Hamara Adab, Shakhsiyat Number-1, (1984–85), J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, p 64; Dar, Shiraz Ahmad, Shah Younus Rashid, Prostitution, Traffic in Women and the Politics of Dogra Raj: The Case of Kashmir Valley (1846–1947), Journal of Society in Kashmir) His main target were poor girls from the lowest sections of the society who were easy prey. Such women were also smuggled to other parts of British India like Calcutta, Bombay, Peshawar, Quetta, etc. The British authorities often asked Jammu and Kashmir Government to arrange the return of these hapless women. (Lal, Jiwan, Traffic in Women for Immoral Purposes, File No 459, Subject: Traffic in Women, Accession Regs. No. Misc/4293, Head: Municipality, Year 1986–87 Samvat, State Archives Repository, Jammu)

In 1931, some conscientious Kashmiri Muslims who visited Punjab or had adopted their residence there, wrote a memorial to Maharaja Hari Singh seeking “immediate and stringent measures” to stop the smuggling of “simple-minded girls and women” from the State to Punjab. They were aghast on the condition of these poor souls who had been tricked into the profession of shame by women traffickers. The signatories to the memorial included Mohammad Sharief, Municipal Commissioner, Amritsar, Katra Mian Singh, Ghulam Hassan Mattu, Katra Bagh Singh, Ghulam Mohiuddin, Advocate High Court, Saifuddin, Retired Subedar Major, Amritsar, Ghulam Mohammad, Mohammad Sadiq and Hissamuddin. After usual salutations and tributes to the Maharaja, the signatories expressed disgust and shame on the plight of the smuggled State girls and women and sought the ruler’s intervention in stopping this horrible practice. An excerpt:

“[T]hose from amongst us who visit Punjab for trade or who have adopted their residence here find to our utter disgustment [sic] and shame that scoundrels from the Punjab and other places visit Your Highness’s State and entice away the ignorant girls and children from there for prostitution and other immoral purposes in this Province.

We must confess that we are profoundly ashamed at the sight of these simple-minded girls and women who are the dupes of professional traders in women and girls and we cannot tolerate this afear insult to our self-respect and Your Highness’s prestige and administration.

Therefore, we respectfully and hopefully submit to your Royal Highness to kindly [take] immediate and stringent measures to put a stop to this nuisance and save us and the State from shame and bad name.” (File No 157/ Pl- D-74, Year 1917, Chief Secretariat Office, Subject: Promulgation of a notification regarding the prevention of activities of prostitutes and their agents in Kashmir, State Archives Repository, Jammu)

The Inspector General of Police, Gandharab Singh, almost washed his hands of the responsibility by blaming Kanjars (women traffickers and their agents) for the “shameful business.” (File No. AR 4174 of 1958, Abduction of Women from the Kashmir State into British Territory for the Purpose of Prostitution, Police Minister’s Office, State Repository Srinagar) Singh claimed that they procured young girls from poorer families on the promise of marriage and then sold them to brothels in Punjab. In an official communication dated 11 September 1931, the IGP admitted that the police were not able to arrest any offender even as the nefarious business was going on under its nose. Singh also revealed that the District Magistrate who also held the office of the Governor of Kashmir, vetoed a proposal to not allow transportation of women outside the State territory without a permit issued by a competent authority.

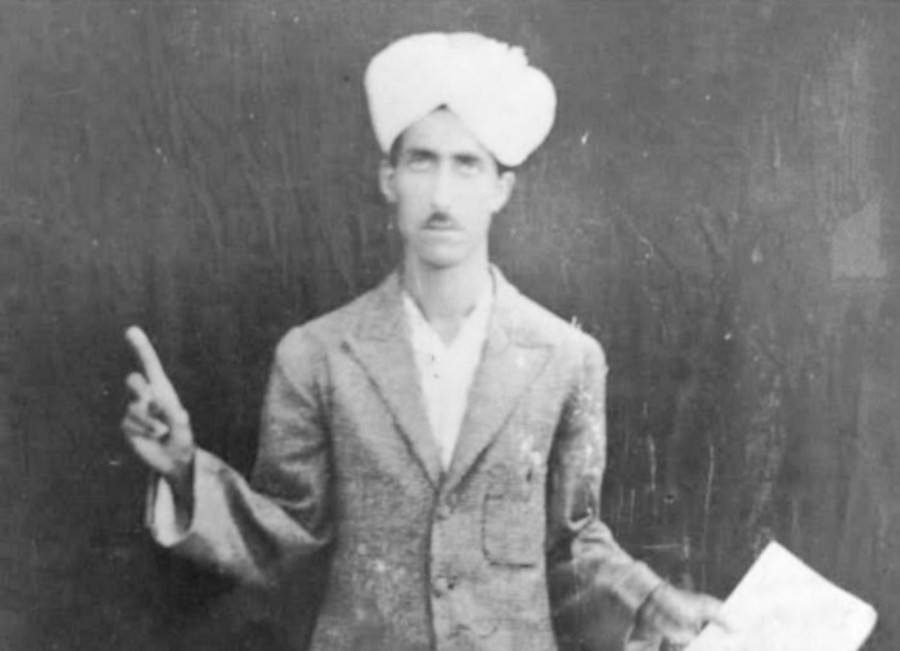

Mohammad Subhan Hajam (1910–1962)

Under a suffocating system such as that prevailed in Kashmir, there was no public resistance against the exploitation of women happening with official blessings. There were no political leaders around as no political activity was allowed. However, the silence of religious groups was intriguing as was that of the men of influence who mostly came from the minority community. Both sections of the society were privileged classes enjoying exemption from taxes and exactions that otherwise broke the spine of a common man. In such a sickening atmosphere, Mohammad Subhan Hajam, a teenager, from Maisuma in uptown Srinagar, rose as a One-Man Army against the scourge of flesh trade and, notwithstanding hurdles, intimidation, ridicule, harassment and prosecution, fought a long and relentless battle for its eradication. Subhan, an illiterate, was the son of Abdur Rahim Hajam of Goripora (Hyderpora) in Srinagar who was a barber by profession and had shifted his residence to Maisuma. Born in 1910, Subhan had three siblings including a brother and two sisters.

When Mohammad Subhan Hajam was born, soliciting by prostitutes and their agents in Srinagar was “brazenly practiced in public”. (File No 157/ Pl- D-74, Year 1917, Chief Secretariat Office, Subject: Promulgation of a notification regarding the prevention of activities of prostitutes and their agents in Kashmir, State Archives Repository, Jammu) In 1917, EJ Sandy, Secretary, Church Mission Society Calcutta wrote a letter to the British Resident in Kashmir conveying disgust felt by European and other visitors over this public nuisance. The perilous situation was reflected in internal communication of the Governor of Kashmir where he wrote that “[t]he nefarious and illicit traffic in women in Kashmir has of late developed into a serious menace for the society threatening to sap its very foundations.” (File No. AR 4174 of 1958, Abduction of Women from the Kashmir State into British Territory for the Purpose of Prostitution, Police Minister’s Office, State Repository Srinagar)

The worst part was that there were no rules or instructions, let alone law, in force to prevent such activities. On the other hand, the only rule that was in force was issued by the Governor ordering prostitutes to “approach visitors only through the Lambardars and that also in no time except between sunset and sunrise.” (File No 157/ Pl- D-74, Year 1917, Chief Secretariat Office, Subject: Promulgation of a notification regarding the prevention of activities of prostitutes and their agents in Kashmir, State Archives Repository, Jammu) The Resident was constrained to advise the Government in Kashmir to take some steps to reduce the evils as much as possible. In April 1917, the Government issued a notification stating that whoever, in any street or public place, within the Kashmir valley “loiters for the purpose of prostitution or importunes any person to the commission of sexual immorality shall be punishable with fine which may extend to fifty rupees.” (Ibid)

As a teenager, Mohammad Subhan Hajam observed young girls being exploited and forced into prostitution and the houses of ill-fame causing nuisance to society. He lived in the vicinity of some houses of ill-fame at Maisuma and was greatly distressed by the goings-on there. The vulgar songs accompanied by musical instruments and squabbling by men continually disturbed him at night but what really upset him were “the cries of anguish from the unfortunates recently forced into this cruel life.” (Biscoe, Tyndale, Tyndale Biscoe of Kashmir: An Autobiography, p 259.) Many of these girls were quite young who were sold by their relations under the pretence that marriages had been arranged for them. (ibid) Feeling distraught by the cries of unfortunate victims, Subhan decided to act and, at the age of 14, he published a pamphlet against the flesh trade and the nexus between the ruler’s officials and brothel-keepers. One day, he picketed a notorious brothel at Maisuma, reciting condemnatory verses and restraining people from going inside. Several children of the locality assembled there and joined him. Accompanied by these children, he then marched to Khanqah-i-Moalla reciting his verses against prostitution and brothel-keepers. His slogan was Niklo kanjro shehrun paar (Kanjars, get out of the city). From Khanqah-i-Moalla, the small procession marched towards the locality of Makhdoom Sahib. That day, Mohammad Subhan Hajam, Kashmir’s crusader against the flesh trade, had loudly announced his arrival.

A barber by profession like his father, Subhan was a clean-shaven, lean man of whiteish complexion and medium height, and spotted short moustaches. He wore kameez pajama, coat and a white turban. Educationist and Christian missionary, Tyndale Biscoe, described him as “[a]n insignificant looking little Muhammadan” and a “gallant little barber”. (Ibid., p 259–60) Wazira Begum, Subhan’s daughter-in-law, remembers him as a hans-mukh or a smiling face. He owned and run Prince Hair Cutting Saloon located in a shop line, mostly comprising shabby roadside eateries, situated behind the (now in ruins) Palladium Cinema. Ghulam Nabi Tanveer, 75, who had seen Subhan Hajam at Lal Chowk umpteen times while going to and coming from his school, recalls that his shop was located at the mouth of the Palladium Lane near the Budshah Bridge where now stands Bombay Gujarat Hotel. (Tanveer in an interview with this author on 30 July 2022 ) The shops and the nearby tonga station were demolished during the premiership of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad to pave way for the construction of the Budshah Bridge. No compensation was paid by the Government for the demolished saloon. According to Wazira Begum the saloon was a two-floor structure and, at one point in time, her father-in-law lived in the upper floor while the saloon was located in the ground floor. (As narrated by Wazira Begum in an interview with this author on 18 July 2022.) The saloon offered hair-dressing and hot-bath facilities. The hair-dressers employed by Subhan wore uniforms. Later, as compensation for the demolished shop, Bakshi reportedly offered Subhan Hajam land at the present site of Budshah Flats or near Haji Masjid Thana if he became a prosecution witness against Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah in the conspiracy case against the sacked Prime Minister. He refused to take the bait.

Although in the fight against prostitution Subhan Hajam was a lone ranger, there were few people who helped him behind the scene or joined him in picketing the brothels. They included Tyndale Biscoe, his wife, and two brave ladies of Maisuma, namely, Haja Bagwani and Rehti Bagwani and Master Mohammad Sidiq. Wazira Begum claims that local molvis or religious men were not happy with Subhan’s association with Biscoe. They accused him of conversion to Christianity and issued a fatwa against him. Wazira Begum says that Biscoe had lent him Rs 600 which he returned in instalments to the last penny. The fatwa did not deter him from pursuing his mission. He went from door to door to persuade prominent citizens and neighbours to rise against the flesh trade, held demonstrations at the doors of brothels and dissuaded visitors from entering these houses of ill-fame. His saloon was a meeting point for a few concerned citizens feeling bad over social evils, crimes and shenanigans afflicting society. They included Sona Khushu, Naba Lasha, Jabbar Khan, Qadir Gilkar, Master Sidiq and others. (Akhtar, Bashir, Suble Naevid (Subhan Hajam), Hamara Adab, Shakhsiyat Number-1, (1984–85), J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, p 59.) Subhan would hold meetings with these men and ponder over measures to rid the society of these evils.

Subhan Hajam wrote and published several pamphlets and leaflets drawing the attention of the people and the Government to the social waywardness and functioning of brothels under official patronage. Titled Hidayat Nama (Guideline), he distributed these pamphlets and handbills in hundreds in the city. During the day, he would appear in a street, make a speech and generate public opinion against the flesh trade, and, during the night, stand outside a house of ill-fame to dissuade people from going inside. His forte was the verses of ridicule that he composed in Kashmiri and Urdu and used them as a sword, always out of the sheath against all kinds of shamelessness. The verses were pungent, hard-hitting and exposed women traffickers, causing strong public aversion against them.

The brothel keepers did not take kindly Subhan’s battle against them. They ganged up, became active and, with the help of police, dragged him to the courts. He was chased, harassed and roughed up several times. Raids were frequently conducted at his home to arrest him but every time he gave police a slip. He wore burqa to hide his identity and move from one place to another to escape arrest. He used a boat at Buchhwor as a hideout whenever police hunted for him. At times, he would spend the night in a nearby corn field. One day during a police raid, he was at home and could have been arrested but for his sister who dressed him in a burqa and evacuated him through a neighbour’s compound. The trumped-up charges against him were continual and “by degrees, he was ruined and had to sell up in order to pay the law costs.” (Biscoe, Tyndale, Tyndale Biscoe of Kashmir: An Autobiography, p 260) The charges were outlandish and included disturbing the law and order situation, maligning respectable citizens, inciting people against the Maharaja and the Government, intentionally causing loss to the revenue of the Government, demanding bribes from the people and resorting to hooliganism. (Qadri, Shafi Ahmad, Biscoe in Kashmir, p 91. ) His enemies, out to destroy him, took away his sole source of income in the state band of the Maharaja where his job was to cut the hair of about seventy employees. False charges against him were brought up to the officer in charge of the band and he was dismissed. Broken but not vanquished, he continued his fight. Two years after he had started the battle against immorality, he wrote in a poster that while his aims and objectives were for the “good of the country, nation and the ruler”, his opponents in league with the police had tried to kill his “harmless movement”. He alleged that several cases were framed against him and he was threatened with life. His movement was labelled as political and the ears of the Government and the District Magistrate were poisoned against him. “But all this went in vain and no power of the world could defeat our resolve”, he wrote.

In the hour of need, Tyndale Biscoe came to Subhan’s rescue and he was engaged in Eric Biscoe’s Prep. School for ‘cutting hair of 100 British Masters and boys.’ Later, in one of his Urdu posters titled Jalay Dil Ki Dardmandana Pukar (A painful call of an embittered heart), a grateful Subhan Hajam acknowledged Biscoe’s encouragement and assistance that enabled him to restart his business. (Mohammad Subhan Hajam’s grandson, Javied Ahmad, shared with this author some published material of his grandfather including a soft copy of this poster which the latter thankfully acknowledges.) “Bless Late Mr Biscoe who encouraged me and provided assistance in this national service to enable me to restart my business”, he wrote. Through another poster titled, Dardmandana Appeal (A Painful Appeal) made to the people of Kashmir, besides acknowledging recognition by Biscoe, “a foreign Christian”, of his services to the country and helping him with a handsome amount of money from his own pocket to cope his dilapidated economic condition and construct an excellent shop adjacent to the Palladium Talkies where “I restarted the business that had been snatched from me during the movement (for the elimination of prostitution), Subhan also hoped that his Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Christian countrymen would patronize him by visiting his saloon. He alluded to the situation of penury he was forced into due to the cases fabricated against him and occupation by the vested interests of a piece of land that he had purchased at Maisuma for the construction of his house. This, he told his readers, was done by his opponents to deter him from doing a national duty. “Gone is the goose that did lay golden eggs. These persons can neither usurp people’s rights nor will I stop from performing my national duty”, he reminded them with a resolve to continue his fight as a ‘Khadim-i-Quom (Servant of the Nation) which sometimes he interchanged with Khadim-i-Wattan (Servant of the Country), the title that he gave himself in his published writings. He had a word of gratitude for the lawyers also who represented him in the courts. “Since my movement was based on sincerity and was for the public good most of the lawyers did not charge any money for representing me in different cases”, he wrote.

Subhan’s commitment to his mission was total and no monetary temptation could shake his resolve. This is perhaps best illustrated by an incident quoted by Biscoe in his autobiography. According to him, one night when the valiant barber and some of his friends were picketing a certain house of ill-fame, a police officer who was the son of a high official arrived in the cover of darkness. Subhan begged him not to go inside but without avail. He then telephoned the official to inform him where his son was. The official rushed to the spot and, to his surprise, Subhan did not demand any hush money for keeping the incident a secret. He made a strange demand: “I do not ask for money, but if you wish me to keep the matter quiet regarding your son, you must have all this traffic stopped.” (Biscoe, Tyndale, Tyndale Biscoe of Kashmir: An Autobiography, p 260.) The high official agreed and soon all such places were ordered to be removed from the municipal areas of Srinagar. Later, Subhan admitted “enough help from the hukam-e-waqt (rulers of the time)” leading to the “elimination of the dishonoured occupation”, and “wiping this black spot from the face of Srinagar and its outskirts.” (An excerpt from the poster Jalay Dil Ki Dardmandana Pukar published by Mohammad Subhan Hajam.)

Four years after Subhan Hajam had started his crusade and was active on the streets and in front of the houses of ill-fame, the Government appointed a committee in 1927 that recommended the formation of a special branch of the CID to deal with offences related with women trafficking and undertaking effective and active propaganda to educate the public opinion and rouse social conscience against the evil. Religious persons and informers were engaged to educate people and watch on and report women traffickers, respectively. But the melting of the hearts of hardened professionals, who made a living out of women trafficking, through preaching was unlikely. The Lambardars, Zaildars and Chowkidars were made responsible for the prevention, detection and conviction of offences of women trafficking, and were held liable to dismissal if these offences frequently occurred in their villages. However, when a proposal was made for legislation on suppression of immoral traffic on the pattern of Punjab, the Revenue Minister of Jammu and Kashmir objected, arguing that not many complaints were received about girls being kidnapped to force them to live a life of shame and to make commercial profit out of their lives of vice. This, when press and public both in Kashmir and Jammu were crying hoarse that traffic in women was on the rise.

Meanwhile, Subhan Hajam resolutely continued his campaign, facing hurdles and police action. On 15 Sawan 1991 Samvat, corresponding to 30 July 1934, a First Information Report under section 36 of the Police Act was filed against him in the Police Station Shergarhi. The charges brought up against him were that he had collected people on the public thoroughfare in the Maisuma Bazar and was sermonizing them against visiting brothels. The thoroughfare was blocked and the movement of people was disrupted. The case titled ‘State through Police Station Shergarhi versus Subhan Hajam son of Rahim Hajam’ was heard by the City Judge, Pandit Bishambar Nath. Subhan denied the charges. He claimed that he was counselling the people on the sideway and they had not gathered on the road. Head Constables Sham Lal and Shambhu Nath appeared as prosecution witnesses while Juma Ghasi, Maqbool Khan and Khaliq Parra were the defendant’s witnesses. The judge observed that the defendant’s witnesses had stated that the accused sermonized people near Mandi Shora Khan and it was not within the realms of possibility that he would have addressed them in the midst of the road. Such a thing could not be expected from a sensible person, they argued. The second question meriting consideration, the judge wrote in his decision, was whether this action of the accused invited section 36 of the Police Act. The accused was not committing any act violative of law but was sermonizing the people to correct their morals. If the gathering of people who had come to listen to his sermon caused obstruction to the movement of the public then it was not the responsibility of the accused. The prosecution had not stated that the accused was lecturing in the midst of the road, and if, as often happens, he was counselling people on one side of the road and they began to assemble there then the accused could not be held responsible for the gathering. On 16 Katak 1992 Samvat, corresponding to 1 November 1935, the court set Mohammad Subhan Hajam free in view of the failure of the prosecution to produce evidence in support of its case. Subhan published the decision in the form of a poster in Urdu titled Naql Faisla (copy of the decision) for mass circulation.

The valiant reformer was not deterred by adversities. However, he had an unpleasant feeling that in his fight against the vice he did not receive the support he deserved especially from the Government. He complained about it in one of his posters titled, Hakumat aur Awam ki Khidmat mai Hajam ki Faryard (A Barber’s Cry Before the Government and the People) where he regretted that the police were not helping him and that some courts also were not discharging their responsibilities adequately. He felt that if his efforts were supplemented by Government help prostitution in Kashmir would be uprooted. (Akhtar, Bashir, Suble Naevid (Subhan Hajam), Hamara Adab, Shakhsiyat Number-1, (1984–85), J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, p 71) The Government not lending a helping hand was understandable because of the revenue the flesh trade generated but, strangely, no religious leader also came forward to his help. They maintained a safe distance from him. When he started his crusade as a teenager, there were no political parties but when the Jammu & Kashmir Muslim Conference was formed in 1932, the menace of immorality continued to seriously threaten society. At such a time, it was expected of the political leadership to openly come forward against it but that did not happen. The ‘strongest’ reaction the Muslim Conference offered was a mild disagreement on the Glancy Commission’s observation on the flesh trade in Jammu. The party’s president, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah wrote to the District Magistrate, Kashmir, that the evil was not confined to Jammu Province and that Kashmir was also in its grip. He asked the Government to “redouble” its efforts in the eradication of prostitution. “Unless the nefarious traffic is nipped at this stage it is bound to extend its tentacles in all directions and then it will be too late to eradicate it” (File No. AR 4174 of 1958, Abduction of Women from the Kashmir State into British Territory for the Purpose of Prostitution, Police Minister’s Office, State Repository Srinagar), Abdullah stated. Throughout the decades of 30s, 40s and 50s of the 20th century when Abdullah was very active in Kashmir politics and Subhan Hajam was fighting the people’s battle on a different front, one does not see the mass leader extending even lip support to him. Subhan Hajam, one may recall, was a strong Abdullah- supporter in so far as his political views were concerned, although he took good care in spelling out that his movement was apolitical and that he neither supported Mirwaiz Yusuf Shah nor opposed Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, leaders of two warring factions of Kashmiri Muslims. At this stage, even the Government was of the opinion that Abdullah’s attention might be drawn for undertaking an effective propaganda campaign against the flesh trade. (File No. AR 4174 of 1958, Abduction of Women from the Kashmir State into British Territory for the Purpose of Prostitution, Police Minister’s Office, State Repository Srinagar.) Subhan was also ignored by the chroniclers of his time. While we observe a contemporary Tyndale Biscoe paying rich tributes to him in his autobiography, a prominent local scribe of the period, Molvi Mohammad Shah Sadat, who maintained a diary of daily events later published in a book form, has not made even a passing mention of this phenomenon.

Almost simultaneously with Subhan Hajam fighting a lone battle against immorality in Kashmir, Lala Jiwan Lal, a Court Inspector, fought a similar battle in Jammu through his pen. It appears that Subhan kept himself posted about the fight against flesh trade in Jammu. In one of his posters, he informs his readers that the people of Jammu had informed about the presence of a brothel at Mohalla Baba Jeevan Shah where a journalist was caught in an immoral act. Lala Jiwan Lal wrote two books and a pamphlet in vernacular on Insidaad-e-Burdah Faroshi (Occlusion of Flesh Trade) to create public awareness about the scourge and seek government indulgence in curbing it. He also came up with a proposal for rescue and training homes at Jammu and Srinagar for the unfortunate victims of the flesh trade. The proposal was circulated among the highest echelons of power and received the Maharaja’s nod. When the Government appointed a committee to suggest measures for the elimination of women traffic in the State, Lal was made its secretary. Other office bearers of the committee included Mirza Ghulam Mustafa as President and Mohammad Assadullah Pleader, Jia Lal Kilam, Tara Chand Trisal, Mohammad Jawad Ali and Sardar Matha Singh as members. Ironically, Kashmir’s iconic crusader against the flesh trade, Mohammad Subhan Hajam, did not find a place in the committee.

Subhan’s fight ultimately bore fruit on 2 November 1934 when the Praja Sabha (State Assembly as it was known) passed ‘The Suppression of Immoral Traffic Regulation’. Earlier, Mohammad Abdullah Vakil, Member of the Assembly, had sought legislation banning prostitution. The Regulation received the assent of the Maharaja on 23 November 1934 and came into operation on 6 December 1934. It provided for the suppression of all brothels within Municipal limits and town areas and imposed heavy penalties on persons who lived on immoral earnings of women and procured or imported a woman or a girl for prostitution. Rigorous imprisonment was also provided for soliciting in streets or public places. Soon after the enactment of the Regulation, police in Srinagar took action against brothel-keepers. About 20 houses of ill-fame were reported to the courts and summons were issued to brothel keepers including some women. (The Tribune dated 7 March 1935.) The public opinion generated by Subhan Hajam had its desired effect in as much as people began to stand up against the evil and evil-doers who functioned as an organized mafia. In one such case, residents of a quarter in old Srinagar city, adjacent to a famous shrine, namely Assadullah, Azim Baba, Khawaja Hassan Shah et al. published letters in several newspapers including Martand, Rehbar, Islam, Zulfikar and Kesri about the presence of a brothel in the area and sought its removal and action against the brothel keeper, Ahad Halwai. The public pressure forced the police to take action. The culprit was sentenced to 6 months of rigorous imprisonment by the City Munsif Srinagar. He went in appeal in the Sessions Court but the appeal was rejected and the sentence upheld.

The Government’s decision to ban prostitution through legislation was celebrated by Subhan Hajam with the publication of Hidayat Nama 6 taking potshots at kanjars and their loss of evil livelihood. A sample:

Khosh khabar boozem dil chum nawnie

Gaane byol galenai galnai aaw.

Naiev chhikh ne yiwan, prain chhikh tchalnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Kaarbaar band gokh kenh chhukh ne chalnie

Doh yuhund dulnie dulnie aaw

Sokh rov ganan te dokh pyokh tulnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Moolan drot log bad khaslatan nie

Shikse kis zaalas walnai aai

Doh khote doh chhekh shahmat walnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Sharhuk makh chhukh lang lanji thalnie

Dalnie chhe gemetch eere wen naav

Shaal yusne poshi su chhu ade tchalnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aav

….

Teel yei watji diwan chhei kalnie

Sais dale daji seet chhukh karaan waav

Pump shoes lagaan chhie goe’r nalnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Nasihat karnuk farz os malnie

Lukan bronh timan maze amuik tchaav

Islamuk gaerat zanh ti gokh ne dalnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Subhan Naevdas gametch bamnie

Pooshide roozith noan yeli draav.

Malkul moat chhui yiman gaane dalnie

Gaane byol galnai galnai aaw.

Translation:

[Heard this heart-blossoming tiding:

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

No new visitors, the old are deserting them

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

With business shut, nothing works for them

Their day is setting.

Flesh traders’ peace is gone, saddened are they

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

The vicious are utterly destroyed

They are caught in the net of bad luck.

Every day, adversity embraces them

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

The axe of Shariah is cutting their twigs

The boat of pimps is capsizing.

A timid jackal runs away from a fight

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

….

When women of low morals oil their hair

Pimps fan them with scarves.

Pump shoes they wear on their ugly feet

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

Exhortation was the job of mullahs

But they relished it before other people.

Islam’s honour did not touch evil pimps

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.

Subhan barber turned in to a catastrophe

When from hiding he came in the open.

He is the Angel of Death for these pimps

Progeny of flesh traders is on the wane.]

The optimism enthused by Subhan Hajam was short-lived, for he soon observed that the rich kanjars in the city were safe and openly carrying out their evil business. In a representation to the District Magistrate made by the residents of Buchhwore and published by him, the officer was informed that in spite of the implementation of the Suppression of Immoral Traffic Regulation, the flesh trade in the city had not stopped and its practitioners were actively engaged in the evil profession. The petitioners alleged that they were receiving threats both from the Government and the kanjars. Earlier, Subhan Hajam had advised the police to prepare and make public names of hidden and open prostitutes and brothel-keepers along with their photographs. This, he believed, would dissuade them from their evil acts. He also proposed that the Government appoint some staff to be posted at the nakas near the brothels to record the names of the visitors to the houses of ill-fame and publish these in the Government Gazette. The Government did not pay any heed to his suggestions. On his own, however, he recorded the names of ‘the respectables’ who visited these houses of evil and, surprisingly, the list included some “zabardast mujahid, bihi khawhan-i-qaum aur shurfa-e-waqt (great warriors, well-wishers of the nation and the respectables of the time)”. (Akhtar, Bashir, Suble Naevid (Subhan Hajam), Hamara Adab, Shakhsiyat Number-1, (1984–85), J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, p 70.) At several occasions, he also published names of the women of ill-repute and their agents or threatened such people of making their names public if they did not stop their nefarious activities. A warning of this kind had the desired effect on two hotels at Lal Chowk used for prostitution. Jalaluddin Shah, 77, former cricketer and oral historian, credits Subhan Hajam with uprooting two notorious flesh traders namely Khizir Gaan and Qadir Magham from the red-light area of Tashwan. (Shah in an interview with this author on 17 August 2022.)

After losing his shop as well as his job with the Police Band, and selling his property to meet expenses on court cases, Mohammad Subhan Hajam took his fight to a new ground. He donned the mantle of a performer, a juggler, so to say, to attract people’s attention and disseminate his message. This time, his main target were quacks and illusionists duping gullible masses and playing with their lives. Those days, hundreds of people gathered round a juggler or a quack was a common sight at Amira Kadal and Badshah Chowk. One would come across Amme Bazigar or Yaqoob Dard Poonchi or a real or fake Afghan, spell-binding people with his tricks or inimitable narration of suspense-filled oriental fables that never reached culmination and, in the process, selling bogus medicines.

Fiction writer and researcher Bashir Akhtar draws an interesting picture of the city centre of those days. According to him, the busiest market of Srinagar, the Badshah Chowk and its surroundings remained packed with street hawkers, quacks, snake charmers, tonga-drivers and streams of people coming from the villages. The present Budshah Chowk was then a tonga station and where the Budshah Bridge stands today was known as Ghat Ishaq Khan. In the midst of the Chowk, there was a five feet high concrete tank, fitted with pipes, for providing water to the horses. All the tongas remained parked around the tank from where they would start their run to different parts of the Valley. In the rush of people, one would find groups of tooth-extractors, snake charmers and illusionists among whom voices of professional crowd-pullers like Raja Yaqoob Khan Dard, Gafoor Khan and Amme Bazigar kept simple villagers hooked. These men astounded the onlookers by their tricks which they did with the help of a snake and a mongoose or a deck of cards, and sold to them self-manufactured fake medicines. “At these gatherings, one would listen to different stories and such obscene words that if repeated at home would have you slaughtered. It was sheer curiosity that hooked us young boys and forced to clap.” (Akhtar, Bashir, Suble Naevid (Subhan Hajam), Hamara Adab, Shakhsiyat Number-1, (1984–85), J&K Academy of Art, Culture & Languages, p 58–59.)

Subhan Hajam had understood the power of crowd-pulling these illusionists possessed. So, he tried to become one of them. Yet, he was altogether different, for he had no axe of his own to grind; no monetary benefit to draw. He had no spicy stories, fake medicines or amulets to sell, nor did he collect money from onlookers. His only aim was to reach with his message as many people as was possible. In doing so, however, he chose the style of professional illusionists, making use of a dugdugi (a small kettle-drum) and a narrative interspersed with some meaningless words [translation]:

“Gentlemen! I am aiwain [nothing] pass, Wular cross, death-bell for the kanjars. I am Subhan Hajam, your servant. This is my newly manufactured tablet. If a brother has pain in the stomach, let him take it with water. If you have back pain, take it with water. If you have headache, take it with water. It is a remedy for all the ailments. After taking one, only one, tablet if you survive you are a hastu [giant] otherwise, if you die you are no-hastu.

So, Gentlemen! I, aiwain pass, will show you all those letters that have come to me from big persons, leaders, rich men, ministers, nawabs, poor men from all over India. Here is a letter received from Bengal and the sender is Rabindra Nath Tagore. He has been benefitted by my medicine and has written a letter of thanks. This letter is from Wazir Janki Nath, this one from Tipu Sultan and this one from Lawrence Sahib.” (Ibid., p 56–57.)

As the onlookers felt over-awed by the heap of post-cards, envelopes and bundles of papers of different colours lying in front of the dugdugi player, he continued:

“O’ my naïve brothers! It looks like Ghulab Singh Dogra has bought your wisdom also. [a reference to the Treaty of Amritsar under which Gulab Singh purchased Kashmir for 75 lakh Chilki rupees from the East India Company following the defeat of the Sikhs, the then rulers of Kashmir, in the Anglo-Sikh War of 1845–46) How simple are you! I swear by the God who created you and me, these letters I have collected from the pile of litter on the road. Where is the comparison between Tagore and a poor me? It is ages since Tipu has died. Now these letters? These I have brought to make an impression on you, exactly the way these quacks rob simple villagers by selling trash medicines to them.

So, Gentlemen! I am thankful to all of you for the support the Gracious you have extended to me in cleaning the flower-capped valley of Pirs, Rishis and Munies of the abominable flesh trade. Now, I want you to extend me your support in eradicating these wheat promising barley sellers.” (Ibid., p 57.)

Subhan Hajam warned against ‘unqualified non-local quakes’ seen in the streets, lanes and markets of Kashmir duping people by selling fake medicines to them that were injurious to their health. Jalaluddin Shah had seen him staging road shows opposite old secretariat and, once, at Namchibal, Fateh Kadal in 1959–60 when Shah was a student of FSC. Ghulam Nabi Tanveer recalls that during a roadshow by a quack or a juggler — among whom he mentions Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Makar Mohalla, Abdul Gafar Khan of Zakura, Mohammad Yaqoon Khan Dard Poonchi and Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Solina — a lean person, wearing a turban, white pajama and a coat and playing a dugdugi, would enter in the crowd and dissuade onlookers from buying fake medicines from the quacks. He would impress upon them that the medicines they were buying were bogus and harmful for them. His narration was a mix of Kashmiri and Urdu and carried even absurd words or phrases to make a comic presentation. A sample:

“Sarde kondal, marde kondal sraad ka

Ye dawai laayi sadak par, ye dawai fraud ka

I am a pass out from the universities of Chadoora and Bab Demb. I am a Wular-crosser. I have received post-cards from people who have bought my medicines that I sell here.

O’ people!

This is all fraud.

Don’t spoil your lives at the hands of these quacks.

Go to doctors for treatment of your ailments.” (As narrated by GN Tanveer in an interview with this author on 30 July 2022. )

Besides flesh traders and fake drug peddlers, Subhan Hajam campaigned against gamblers and sought closure of gambling dens in the city. He also raised his voice against the mujavirs or caretakers of Muslim shrines who, he alleged, were looting the pilgrims. He vehemently opposed free mixing of men and women especially at festivals and appealed people to stop sending their daughters and daughters-in-law to these gatherings. He warned that women at the festivals get inappropriately pushed and their bodies touched by stranger men. “Is it not vulgarity?”, he asked and lashed out at men who let their wives go to such gatherings. His argument was that such mixing of sexes “gave birth to a thousand vices and allowed bad characters an opportunity to play mischief.” (Urdu handbill titled Auratun aur mardun ka qabl-i-nafrat ijtim’a: Mailun mai jaaney say apni baitiyun ko roko issued by Mohammad Subhan Hajam.) He asked the caretakers of shrines to earmark separate days for men and women pilgrims visiting there on urs days. He also drew attention of “self-respecting Muslims and Hindus” to the public bathing cells on the river bank “where men and women bathed naked in the morning.” He called it a “black spot on the white forehead of Kashmir” needed to be removed. In another poster, he restated his concern over free mixing of sexes and warned people against ‘khofnak tabahi’ (terrible destruction) and ‘gumrahi’ (misguidance) this ‘waba’ (plague) would bring in near future. “For the time being, I am addressing the Muslim women and, in the name of God, call upon them not to mix with stranger men if they visit shrines”, he beseeched them.

Another section of the society he was not at ease with and wrote against were the deviant mullahs whom he accused of being prisoners of their desires and playing no role in correcting morals of the people, their prime duty. He, in fact, accused them of blessing the flesh traders and working as their middlemen rather than working against their nefarious activities:

Malle chhi ganan menzimyari

Laraan khore nanwaeri ye

Nafse daadi chhikh karaan khedmatgaeri

Ya Rab asi kar yaeri ye

Kya kari wein saen parhezgari

Mordar malle geyi saeri ye

Ha Khodayi tchhentakh baed bemari

Ya Rab asi kar yaeri ye

[The mullahs are the middlemen of flesh traders

They run towards them bare feet.

For monetary reward, they serve them

O’ Rab! Bless us.

Our piety is useless

For, mullahs are all polluted.

O’ God! Strike them with a major disease

O’ Rab! Bless us.]

In 1936, Subhan Hajam came up with a Kashmiri pamphlet titled, Malan Huind Galat Mazhab (Wrong Faith of Mullahs) under his Hidayat Nama series, exclusively targeting the mullahs. He accused them of being irreligious and misleading people. He especially felt offended by their writing amulets for prostitutes and holding prayer sessions for their prosperity in lieu of some money and sumptuous food. A mullah and a flesh trader are each other’s best friends, he alleged.

Paraan lookan hadisa paane gumrah

Beyis wath haavi kyah yus aasi berah.

Yimav dalav dutui sag gaane wanan

Yihind taveez chhi na’el bad zananan.

Malan tai gan nie chhui poore athwaas

Chhi qaumas kiet doshwai zehar-i-almas

[They preach people but themselves are astray

How can a lost man be the leader of others?

These agents have profited brothels

Women of ill-character hang their amulets round their necks

The mullahs and the brothel-keepers are best pals

Both are toxic for the nation.]

Besides running a saloon, Mohammad Subhan Hajam sold self-manufactured aromatic hair and body oil, tooth powder and ointment. Wazira Begum said that the wooden box he used to stock oil bottles still smelled fragrant. He chose Gulistan-i-Kashmir (Garden of Kashmir) as the brand name for his products. Some of these were Sandalwood Hair Oil “for anointing the body and softening the skin and for beautifying and promoting the growth of the hair”; Jasmine Hair Oil, “a delicately perfumed, an excellent tonic for the growth of hair & is enchanting gift for brain worker”; Brahmi Amla Hair Oil, Tooth Powder, “sure remedy for pyorrhea”; and High-Class Best Ointment Shoo Bulgar, anti-frostbite ointment. In olden times, a barber in Kashmir functioning as a surgeon was not uncommon. Besides performing circumcision of children, barbers were also called to treat boils and operate if a vein of a patient was to be opened.

Mohammad Subhan Hajam had also assumed the leadership role for his community in the capacity of the President of Barbers’ Association Srinagar. During his presidentship, one of the issues confronting the association was about weekly-holiday barbers should observe. Some members of the association wanted Friday as a holiday while others suggested a different rest day. As President, Subhan Hajam announced that there would be no holiday for barbers. They would work all seven days. He argued that barbers were a poor community that could ill afford the luxury of observing a weekly holiday. Their closure of business for a day would also greatly inconvenience the public which was undesirable. He reminded those who wanted Friday as an off-day that Islam did not enjoin upon them to observe Friday as a holiday but only asked them to take a short break for offering prayers and then resume their business. Lastly, he argued that no Government order had bound them to observe a weekly off-day. “All the barbers of Srinagar are informed that in order to improve their financial position they should stop thinking of observing a weekly holiday and continue working nicely and with dedication”, he instructed hairdressers of Srinagar through a pamphlet.

Mohammad Subhan Hajam married twice. After the death of his first wife with whom he had two daughters and a son, he married Mughli Begum from Alamgari Bazar. From his second marriage, he had a son and a daughter. His elder son, Ghulam Nabi, too was a barber and had his shop at Maisuma. The younger son, Ghulam Mohammad was a Foreman at the daily Khidmat Press. He had purchased land at Maisuma to build a house. The triple-storied structure was raised and roofed but before it was ready for moving in, he passed away. The house, later completed by his sons, continues to be part of the skyline of Maisuma. A patient of Asthma, Subhan Hajam breathed his last on 25 November 1962 and was laid to rest at the Malteng Graveyard in the foothills of the Takht-e-Sulaiman (Shankaracharya Hill). At the time of his death, he asked for a cup of qehwa, his cherished sweet brew, which he drank. When he passed away, his younger son was only two and a half years old who was later taken care by his elder brother. His second wife died on 9 October 1999. Among his five children, two daughters are alive. His close friends included Jabbar Dar and Rasool Pulsewoal (Policeman).

Tailpiece:

The autocratic rule during which Subhan Hajam started and run full-speed his campaign was not expected to acknowledge, let alone honour, him but, sadly, the successive ‘popular governments’ too did not consider perpetuating his memory by naming after him a school, a bridge, a street or even a pavement. Be that as it may, the brave reformer shines on the horizon of Kashmir history as a bright star. His contribution to his society is more phenomenal than that of most of our ‘celebrated’ individuals. Salutes to the Great Man!