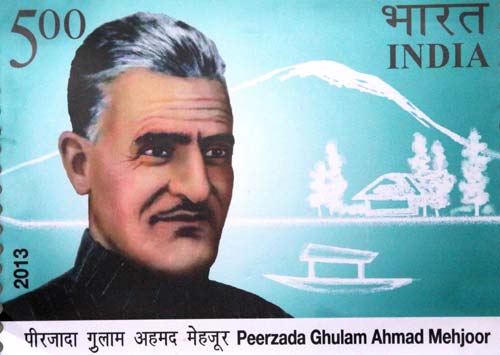

Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh flew to Srinagar to launch a postal stamp in memory of Mehjoor, Kashmir’s national poet, 60 years after his death. The last postal stamp in the Kashmir context was launched in memory of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah in the late eighties. As the Srinagar postal authorities, who were behind the initiative, are busy selling 310 thousand stamps printed in the first go, Kashmir’s well know literary historian and poet Shafi Shauq writes about the wordsmith he has studied for thirty years.

Ghulam Ahmad Mehjoor is now a symbol of Kashmiriyat, with all its nuances. In spite of his complete surrender to the psychological provenance of the romantic language and thorough disappearance of self, demands, for a variety of reasons, ceaseless comment. The author of numerous lyrical poems has hardly left any debatable issues for critical scrutiny, yet professional literary commentators have to say more and more about what has been abundantly said by the author himself. His poetry has an irresistible pull: nostalgia, the intensity of desire to withstand all-annihilating forces, libidinal intensity representing desire, melopoeia and mythopoeia; all these elements combine to atrophy rational questioning.

The originality of Mehjoor’s poem lies in his effort to free language from its use in the takiyas, traditional institutions of Sufi thought and training, and impart it the verve of contingent reality, mainly collective and political. In order to evade the hazards of superficiality, Mehjoor uses mainly two poetic figures: ‘kenning’, a formulaic phrase that describes one thing in terms of another, and ‘litotes’, which is a dramatic understatement employed for producing an ironic effect. Kennings and litotes, ramz wa kinaya in Iranian aesthetics, save him from a direct comment which he feared would invite vendetta, both in the autocratic times and then in the post-independence era; he was critical of both. He chose a poetic idiom, entirely at variance with that of the time-honoured Sufi poetry, and created a kaleidoscopic beauty out of the finite sets like gul ti bulbul (flower and bulbul), bagh ti baagvaan (the garden and the gardener), vaav ti tuufaan (wind and tempest), shabnam (dew) aaftaab (the sun), mas (wine), zeely vaanki (kinky curls), bombur ti yimbirzal (the drone and narcissus), so on and so forth.

In the verses which are representative of an aesthete’s urge to express his sensitivity to things of beauty by portraying common things charged with the inherent beauty of form, seen as if for the first time, or creating new arrays of observable things and release the hidden preternatural energy in them, Mehjoor surpasses all around him. The intensity of such verses is because of their power of suggestion which makes us intensely conscious of the permanence of beauty, stir ardent passion to have it, but at the same time reminds us of the transience of individual life; all the three effects work through his sense of music and myth.

Morning breeze waits in wee hours,

fervently looking for someone it loves,

the flowers jeer it at every step.

When she straights her kinky curls,

light takes to hiding in shining pearls;

redolent gusts suffuse the garden.

Yes, she prefers to live in elfin lands.

I look around while standing at a height,

seeing the garden I get despaired;

the caravan of flowers I behold leaving.

Appreciating Mehjoor depends upon the reader’s understanding of the period of transition from an unquestioned authority of ideas, institutions and power to inexorable transformation under the impact of modern knowledge and culture. It was a time of great revolutions, advances in science and great thinkers. The euphoria of change cannot be appreciated by those who usurped all the material benefits of the change, secured a safe niche in society and then became the vanguards of exclusionism and opponents of the future. Mehjoor was the first poet to represent a futurist concept of man and the notion that man is what he makes of himself. His shift from man as a product of contemplation to man as the product of action is what made him both the most popular poet of his time and the frequent butt of ridicule.

Here is a short lyric that heralds the brave new age:

O Saqi, throw open the doors of the tavern,

be informed and keep you pace with the times;

remove the rust from the glasses and the goblets.

The wine is vended at all the shops,

all cheer their glasses full;

what is now the value of Saqi’s tavern?

The world rejoices its freedom won.

Why should we be servile to the bonds of loyalty?

The freeman obeys no restricted faith.

The morning oriole bears the blame:

it woke up and awakened myriad flowers,

he has been detained in the cage and the cell.

The days are few, use your accoutrements,

you have to brave the tempest in the offing;

people shall otherwise occupy your house.

Mehjoor narrates his tale of love,

engrossed he is in his lucid songs;

no stranger can admire his gestures and signs.

His emphasis was on the common man who mattered in the period of revolutionary events. The emphasis on common man surfaced in all other forms of the common: common people engaged in their common life activities like griesy kuur (Peasant girl), the common language of common rustic people used in their routine life, common usage of words tinged by imagination in order to make them suggestive, and common things and incidents presented in such a way as liberates their intrinsic but hidden wonder.

Professor Shafi Shauq is an authority on Kashmiri language and literature, literary history and Mehjoor. He headed the department of Kashmiri, the University of Kashmir for a long time.