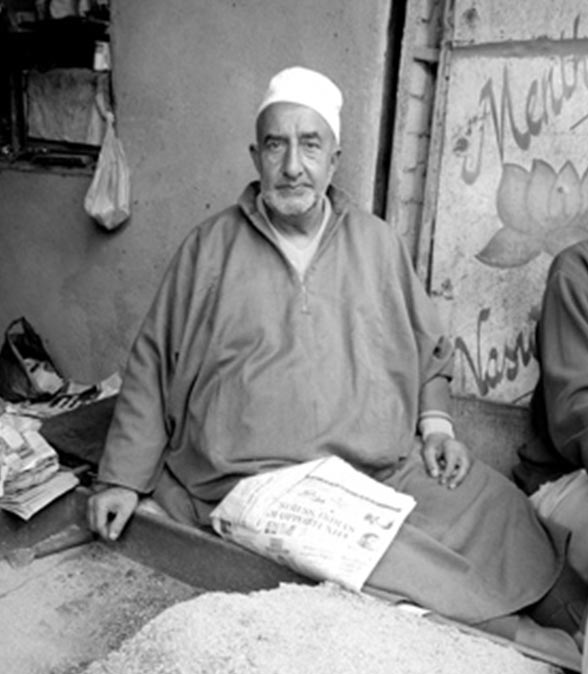

When Ghulam Nabi Chitgar’s hands are busy mixing and preparing tobacco for his customers, his mind is busy elsewhere – composing poetry. Shazia Yousuf profiles the illiterate shopkeeper, who has hundreds of poems to his credit.

Darr dil chum amaar choanui (My heart craves your love) – The radio plays this song of Raaj Begum as shopkeeper Ghulam Nabi Chitgar passes on a tobacco pouch to a customer. “These are my lyrics,” Chitgar whispers to him while dumping a ten rupee bill under the musty rug in his shop at Malarata, Srinagar. Ignoring the cynicism of the customer with a smile, Chitgar returns his greasy hands to the mound of unmixed tobacco in front of him.

From the past 50 years, 70-year-old tobacco seller has been composing poetry. He is illiterate, but his family and friends have documented his more than 2000 poems so far. But the number, he says is just one fourth of his poetry as most of it was “lost due to the absence of a writer”.

“Couplets come to my mind anytime, anywhere, when I am at a shop dealing with customers or in solitude at my home. If some literate person is around, it gets documented otherwise I forget it. I am old… illiterate. I lost many poems even when somebody wrote them for me, as I forget them in my pocket or simply discarded them,” says Chitgar.

He was in his early twenties when he discovered a penchant for verse. “I would do tilla (silver thread) work on shawls in a workshop. There were dozens of other craftsmen. Poetry was a great amusement. I would sing verses to them and they would repeat in chorus. Neither I had any idea of what I was singing nor did they realize that the couplets were mine,” he recalls.

However, there was no let-up. “Poems would come in hundreds” and Chitgar who earlier sang poems to his co-workers would not get time to talk to them.

Verses came at the cost of his work. “My work suffered. All my attention went to poetry. The whole atmosphere inside the workshop changed. And within me, there was fire. I was lost and didn’t care about my surroundings,” he says.

In order to get his “poetry-ridden” brother back on track, Chitgar’s elder brother got him at 30. “I was not earning enough and marriage increased my responsibilities.”

To fight his financial crisis and his obsession for poetry, Chitgar left the workshop and set up a tobacco shop in his locality. Business took off and poetry survived too. In fact poetry would not affect his new job, and his job didn’t distance him from poetry either.

“I couldn’t detach myself from it (poetry).”

Chitgar now tried to record his poems.

“I tried all means to chronicle my poems.” He would rush to a nearby literate shopkeeper friend and ask him to write down a poem. “Many times he would not be there and I would forget the verses. Then my sons kept a tape recorder in my shop that too didn’t work well. There were frequent electricity disruptions and I couldn’t afford batteries,” Chitgar recalls.

One day Abdul Ahad Farhaad, a news reader at Radio Kashmir Srinagar heard him singing his poems in his shop. He took Chitgar to Radio Kashmir Srinagar and introduced him there. “I qualified the interview and they paid me for 21 poems – one and a half rupee for each poem. I am registered under ‘Illiterate Poets’ category for the last 31 years.”

Chitgar’s poems have been sung by famous Kashmiri singers like Habibullah Bamboo, Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, Raaj Begum, and Shaaksaaz.

Seven years back Chitgar took Rs 12,000 from the money he had “saved for daughter’s marriage” and published Asrar-e-Wehdat, a collection of 129 poems. “From that small amount I could publish only a thousand copies. My priceless possession is decaying due to the high price of paper and printing – a tobacco seller like me cannot afford. Maybe someone after my death will do it for me,” he says while seizing a copy of his collection from his mischievous grandchildren.

He “doesn’t seek fame” but would like the authorities to secure his collection for future generations.

“Only learned and high profile people know how to approach authorities. Someone told me that cultural academy pays 75 per cent of the amount that goes in publishing a book but I don’t know how to go about it,” says the poet.

During his 50-year long journey of poetry and life, Ghulam Nabi married off his five daughters and two sons and performed Hajj twice. His elder son works as an electrician while as the younger one helps his father at the shop, “When my children were small I would remain engrossed in my work to feed my family. That time my poetry suffered but now my children are married and earning; I run the shop till lunch after that my younger son takes over. I get lot of time to concentrate on my poetry now,” he says.

Though Ghulam Nabi gets lot of time to compose poetry, his age and failing health is a hindrance. “When I feel like crafting a poem, I get chest pains. At times it becomes intolerable and I have to give up,” he says as his hands work on the tobacco mounds.