Official historic narrative suggests the conversion of the Muslim Conference into the National Conference was smooth. But revisiting the key characters of the change creates a different opinion of the momentous decision of the pre-partition era. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, even lacked support of his wife for this, writes Khalid Bashir Ahmad

The conversion of the Muslim Conference into the National Conference in 1938 turned out to be the single most crucial development leading to political uncertainty that plagues Kashmir ever since. The decision proved to be as momentous as it was controversial. For, it turned the flow of events in 1947 in a direction that subsequently left even Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, who brought about this conversion, a bitter man.

Fifteen years later, in hindsight, the Sheikh saw a point in the warning of Mohammad Ali Jinnah when he was dismissed as prime minister of Jammu & Kashmir and sent to prison in 1953. Repentance then, to put in his words, was “like crying over the spilt milk.” Jinnah had warned him that those whom he was considering his friends [read Jawaharlal Nehru and Indian National Congress] and at whose beck and call he was acting, were not his true friends but his enemies.

Did the Sheikh’s decision to convert the Muslim Conference carry the support of the entire Muslim population of Jammu & Kashmir? The answer in ‘yes’ would be grossly incorrect. The Muslims of Jammu province, constituting a majority of roughly 61% of the total population of the region [Census of 1941], were against the conversion barring a few like Raja Mohammad Akbar Khan of Poonch. It would equally be an exaggeration to suggest that the majority in Kashmir supported the Sheikh’s line on the conversion. The bulk of the population of Kashmir, uneducated and oppressed under a ruthless autocratic rule as they were, had no idea of the import of the decision and, accordingly, could not fathom its implications. They blindly trusted the leader who had stood up for their rights and believed that wherever he led them it would be in their interest.

There was opposition to the move, nevertheless. The educated youth, for one, were against the conversion. A sizeable chunk of the Muslim Conference leadership stood in opposition. Not to speak of the leaders from Jammu like Chowdhary Ghulam Abbas, Allah Rakha Sagar, Abdul Majid Qarshi et al, the Sheikh has admitted, in his autobiography Aatash-i-Chinar, that even his close aides from Kashmir like Mirza Mohammad Afzal Beg and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad too initially expressed themselves against the conversion.

The Sheikh’s warming up to the Indian National Congress had begun in the early 1930s. In 1934, he toured Punjab and met Congress leaders. In 1936, some Congress leaders including Puroshotam Das Tandon, whom Nehru had specifically sent to meet the Sheikh, came to Kashmir.

Next year, Abdul Gaffar Khan and R K M Ashraf arrived in Srinagar in an effort to bring the Kashmir movement closer to the Indian National Congress. The seeds of dismantling the Muslim Conference and building on its debris a ‘nationalist and secular’ party had been sown and in 1937 came the turning point when the Sheikh had his first meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru. The meeting was a result of the former accompanying the latter on his visit to the Frontier Province and culminated in the Sheikh’s formal baptism in nationalism and giving up the apparel of a leader of Muslims of Jammu & Kashmir. His one-time colleague and later adversary, Chowdhary Ghulam Abbas, recalled that the Sheikh “returned from this meeting heavily intoxicated with the wine of nationalism whose hangover did not leave him thereafter.” He was determined to answer the wishes of Nehru to open his party for non-Muslims although they had refused to cooperate with him despite much of his efforts.

As the latter events unfolded, Kashmiri Pandits were not attracted to the National Conference, barring a few youth leaders who, in the words of the Sheikh, joined the party only to mould its policies according to their wishes. They would make a big fuss over starting a public meeting with the recitation of verses from holy Quran or raising of slogans like Allah o Akbar (God is Great). The Pandit indifference had disillusioned the Sheikh and at one time, out of sheer frustration with their behaviour, he had requested them to at least sit on the fence if they did not want to side with the oppressed in their battle against the oppressor.

In Kashmir where he enjoyed widespread popularity, the Sheikh found an appropriate ground to propagate and implement his newly acquired nationalism. However, the Muslims of Jammu were a different case altogether. There, he did not command such respect and love and had to beat a hasty retreat in the face of a stiff resistance when he tried to test the waters for the dissolution of the Muslim Conference. Raja Mohammad Akbar Khan of Mirpur was supportive of the conversion and piloted a resolution to this effect at a session held at Jammu Eidgah in 1937. The resolution was vehemently opposed including by some close aides of Khan and it fell flat. However, a year later, the Sheikh had his way at a convention in Srinagar to bury the very organization that he had, a few years ago, raised as a “credible party to serve as leading contingent of national interests.”

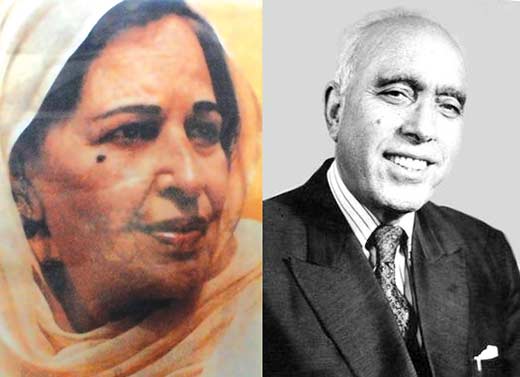

Besides the opposition from his own colleagues within the party the Sheikh also encountered resistance from his wife against the dissolution of the Muslim Conference. Begum Akbar Jahan was not in favour of the move and tried to persuade her husband against taking such a step but the Sheikh was adamant. The issue resulted in bitter arguments between the couple and at one stage even the marital life of the Sheikh was in jeopardy when Akbar Jahan, convinced that he was determined to go ahead with his idea, left her husband and moved in to her parental house. Was Akbar Jahan then under the influence of her mother who, as a family friend described her, was a devout Muslim and anti-India?

A close friend of Harry Nedou, the Sheikh’s father-in-law, Mohammad Sidiq Parray who died on March 21, 2013 at the age of 106, in a long interview with this writer, recalled the differences of the couple on the conversion of the Muslim Conference and said that the Sheikh was tilted towards the Indian National Congress and Jawaharlal Nehru. There appeared ideological differences between the Sheikh and his wife who was “a strong supporter of the Muslim Conference.” Bitter arguments would take place between the two over this issue and ultimately one day Akbar Jahan left her husband’s residence and went to her parental house.

“I was with the Nedous and came to know that Akbar Jahan was upstairs and had quarrelled with her husband over the issue of dissolution of the Muslim Conference. She stayed put there for 15 days. It took lot of persuasion for her brother, Akram, to convince her that as a faithful wife she had to follow her husband after which she rejoined him,” recalled Parray. Akram had told her sister that if she did not go back, her husband might take another wife. Subsequently, she relented and Akram and Parray accompanied her to her husband’s house. After this incident, she fell in line and supported the Sheikh’s political course till his demise.

The failure of the National Conference leadership to win Kashmiri Pandits over to the party had left it sour. There were voices of regret on the dissolution of the Muslim Conference which was ‘martyred’ at the altar of the Kashmir’s minority community. At one point, an attempt was made to reverse the conversion.

In 1944, the Kashmiri leadership had almost reached a consensus on the issue. The General Secretary of the National Conference, Mohammad Syed Masoodi, had gone to his native village in Muzaffarabad and Ghulam Mohiuddin Qarra, the acting General Secretary, sent registered letters to other Muslim members of the working committee informing them that the members from Kashmir had reached an agreement to reconvert the National Conference into the Muslim Conference and asked for their views. Krishan Dev Sethi recalls having read a letter with this content addressed to Raja Mohammad Akbar Khan.

The reconversion of the National Conference did not take place. However, it was left for leaders like Chowdhary Gauhar Rehman, Chowdhary Hamidullah Khan, Syed Hassan Shah Jalali, Khawaja Mohammad Yusuf Qureshi and eight others to revive the Muslim Conference on October 10, 1940. This was around the time Chowdhary Ghulam Abbas severed his ties with the National Conference soon after Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit to Kashmir in May 1940. After remaining politically inactive for two years, Abbas finally lent public support to the revival of the Muslim Conference in 1942.

(Author of Jhelum – The River Through My Backyard, Khalid Bashir Ahmad is a poet and historian. Former Director Information, he recently retired as head of J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages.)