by Javaid Iqbal

In ancient Greek mythology, Sisyphus as punishment was condemned to push a rock up the hills until eternity. The moment he reached the summit, he had to start the gruelling process again. The same is true for education in Kashmir. Every student is a Sisyphus that has been condemned to push a rock without any purpose.

Ten years ago, as a high school student, I used to attend three preparatory centres, besides formal schooling. Today I see students repeating the same mistake. This process results in burnout and a waste of time.

While the world has moved to 3-D printing and machine learning, teaching in Kashmir is guided by information from decades ago. In fact, in my business school education, some of the case studies taught about organizations from the eighties; these organizations have ceased to exist but the cases continue to be taught.

One reason for the stagnation of education is that teachers have no incentive to update their knowledge. This is particularly true of permanent faculty at the universities. They do not even have a scale by which they could measure if they are successful in providing the level of education they claim to offer. What we have is a high stake testing regime that rewards recall of textbook content rather than independent reasoning. Every year students enrol in a programme and then graduate after a few years, and during this time they are not taught any hard skills that could help them get a job and are rarely advised by a career counsellor.

The focus has always been on rote learning and memorization, which has no place in the fourth industrial revolution. Students in Kashmir need to take matters into their own hands because waiting for a top-down approach will result in the loss of the most productive years of their lives. The current educational system of India, and consequently of Kashmir, is a part of our colonial legacy. The reason for creating such a system was to produce factory workers. Such a system was installed to enable people of Western colonies to work in places that required following orders from supervisors. It was not designed to produce leaders for conducting high-level work.

Unfortunately, this legacy has endured. We are stuck in the same education system, imposed by the British Empire, from decades ago. Our education systems are still run on the nineteenth century “factory model” of education. In most of the subcontinent, students are forced to learn at the same speed, in the same way, at the same place, and at the same time, regardless of their individualistic aspirations or talents.

As a result, too many students are struggling to learn because they do not feel motivated by their cumbersome and boring syllabus. There is a significant gap in talent that is in demand and talent that is being produced by this broken education system.

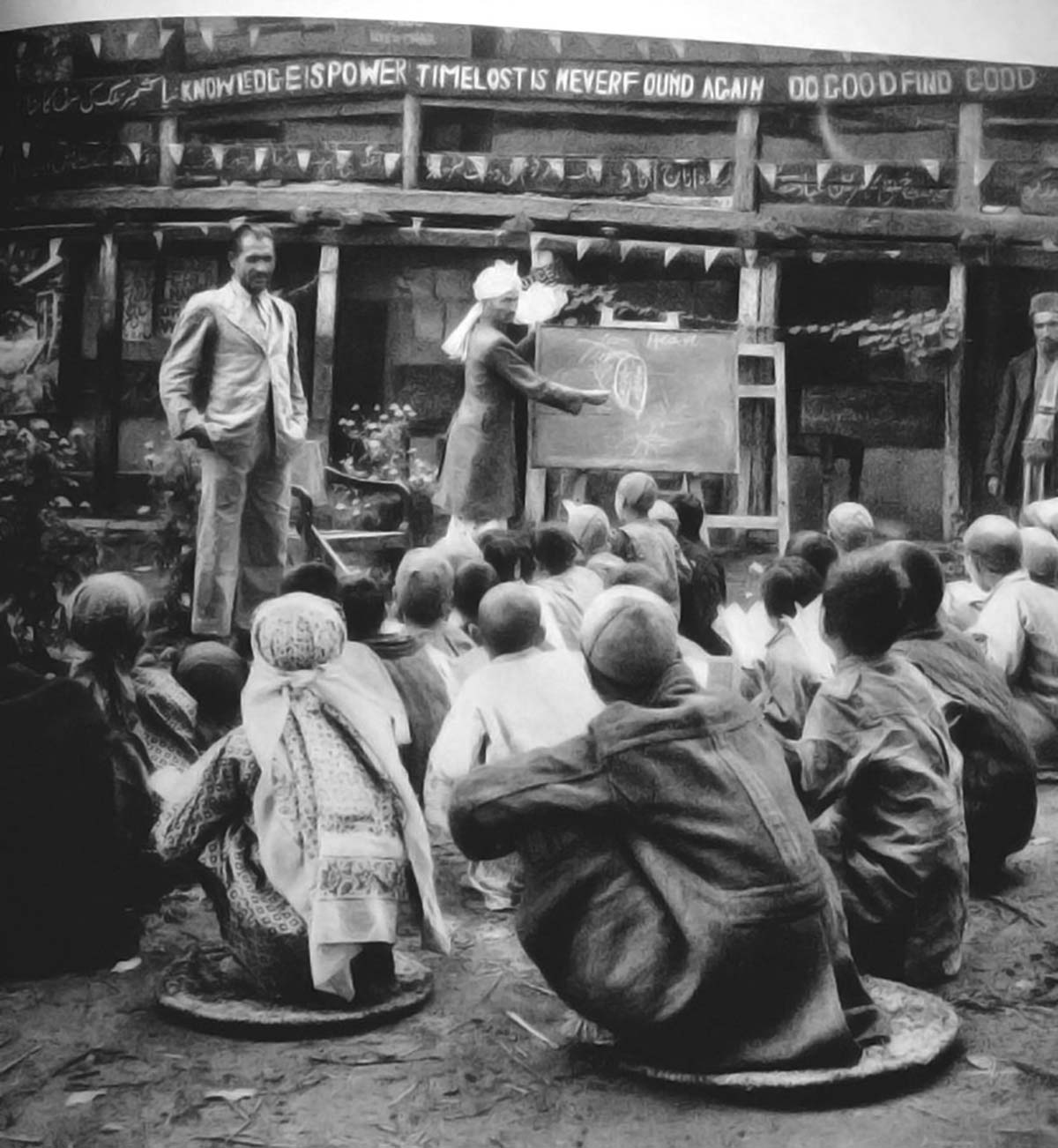

In 1620, Francis Bacon published a scientific manifesto tied The New Instrument. In it, he argued that “knowledge is power”. The actual test of knowledge is not the amount of information we can imbibe, but rather how much it empowers us. Just like we may find the cure to the current virus of Covid-19, but the economic consequences will linger for years, similarly, the impact of a broken education system lingers for generations.

What we need is to prepare our youth for the upcoming job market. Coronavirus will act as an accelerant that will change the nature of jobs, everywhere. Covid-19 will also speed up the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, for online applications that ease remote work. Whereas the industrial revolution took place across several generations, the artificial intelligence revolution will have a major impact within one generation. Automated factories will undercut the one economic advantage developing countries historically had: cheap labour. Robot operated factories will move to be closer to their customers in enormous markets.

According to the World Economic Forum, in just five years, 35 per cent of the skills deemed essential today will change. There is only one way to remain relevant in a post-Coronavirus reality: commit to a lifetime of learning.

Many countries are heading for a very sudden and unprecedented economic recession. Few industries can avoid being reformed, restructured, or removed. McKinsey consultants have projected that up to 30% of jobs in the US will be automated by 2030, and that “automation and AI will lift productivity and economic growth, but millions of people worldwide may need to switch occupations or upgrade skills”. The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) reported the cost of robots continues to decrease, enabling wide adoption. South Korea has seven robots per 100 workers and every third robot installed is in China.

A 2019 report by Oxford economists predicted that 12.5 million manufacturing jobs will be automated in China by 2030. In the pandemic’s aftermath, it could be many more. Because of Covid-19, even Tata Steel which used to employ thousands of contract workers for machine maintenance work will now use sensors that can predict breakdown well in advance. Almost half of the company leaders in 45 countries are speeding up plans to automate their businesses, as the Coronavirus outbreak has forced workers to stay at home during the pandemic.

The World Economic Forum has also estimated that the emerging professions resulting from automation could lead to a generation of 6.1 million jobs globally between 2020 and 2022. This means that there is a crucial opportunity, as developing skills for future jobs have never been easier. Today, it doesn’t require years of study or expensive loans to build up the skills in coding to be prepared for a post-Coronavirus world. There are endless free online courses, on websites such as Coursera or edX that are available.

The question is how soon educational institutions wake up to this reality.

This is first of the 2-part series on education.

(The author is a global fellow at the Heller School of Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University and also at the Institute for Economics and Peace. Idea expresses are personal.)