After emerging as a rebel in Indian politics, George Fernandes was involved in Kashmir, directly and indirectly, for a long time. In tumultuous 1990s, he became VP Singh’s Kashmir Affairs Minister but Delhi’s policy circuit was a devastating triangle that prevented Home Minister Mufti Sayeed, Governor Jagmohan and George to have a common minimum basic. Many think the troika pushed Kashmir to the abyss of a crisis that it is yet to come out from, reports Masood Hussain

On the Friday morning of March 9, 1990, when I reached the office, I saw Manzoor Kahnpuri restlessly waiting for me. A friend of my editor Mohammad Shaban Vakil, an erstwhile contractor, he would spend his day at the al-Safa News, collect Kashmir reportage from English media and attempt drawing cartoons. “We have to go to Chanpora, there has been a serious incident,” he said hurriedly. I worked at al-Safa till I was sacked in April 1990.

There was no traffic around. As we trekked the “long” distance, Khanpuri detailed the CRPF raid on a small locality during which the womenfolk made serious allegations. Readers of this “modern era” would be shocked to know that the raids had taken place on March 7, evening. It took more than one day for the news to reach the newsrooms, barely 4 km away. That was the 1990s.

We reached a particular cluster and landed in the home of a senior citizen who arranged our meeting with the women. After recording the statements, we visited their modest homes and saw the broken furniture. Almost all the women we met were crying over the molestations, and two of them actually alleged rapes by the CRPF personnel, which apparently was “retaliating” a militant attack nearby. The detailed news was out on March 10. During raids, the CRPF had taken a father and son with them and the locality was desperate to know about their whereabouts.

“On March 7, following a firing by militants on the CRPF at Chanpora, the latter raided houses in the locality,” the Committee for Initiative on Kashmir reported in its widely read India’s Kashmir War. “We visited the area on March 14, and interviewed the victims, mainly women who were molested and raped by the paramilitary forces.”

The report named two sisters-in-law who were raped and mentioned two teenagers who survived molested. It mentioned a daughter-in-law who jumped from the first-floor window and survived the assault. “The residents took us around the locality and invited us to their houses, where we saw household goods destroyed by the CRPF-broken TVsets, radios, glass utensils and mirrors strewn all over the place,” the report said. “At least 15 families had left their homes.”

On March 16, evening, Vakil came hurriedly from a meeting and told me that an important person wanted to meet the victims and it was important. Somehow, I managed the telephone number of Goras’, who live in the locality, and informed them about the late evening visit of “an important person”. By around 11:45 pm, Vakil accompanied me downstairs where an official ambassador car was waiting. As the doors opened, it was George Fernandes inside. We got into the vehicle and left for Chanpora.

That night, like all other nights of the early 1990s, the fierce sloganeering had reached a new pitch. Oblivious of the tensions around, we reached Chanpora where the men and women of the locality briefed George about what CRPF had done to them. They relived their tormenting experiences as George was recording their statements on a tape-recorder he carried with him. Though most of the womenfolk had migrated out of fear, some of them had stayed put. He met almost a dozen women and men, a few of them injured.

“Your daughter is my daughter and your mother is my mother,” I remember George telling an angry young man. “You will get justice, I assure you that.”

Initially, he was very attentive. Later, when the people started narrating their experience in Kashmiri, I remember he fell asleep, intermittently. Occasionally, however, he would open his eyes and check that his tape-recorder was working. “You sent Jagmohan and he said he would work like a nursing orderly,” one young man told him while showing the broken household items in his modest home. “This is how your nursing orderlies work!” He saw the medical reports of some women and visibly was shocked by their statements.

Later, he asked some government officials about the working conditions, salaries and other things. “You sent Kashmiri Pandits to Jammu and gave them the salaries,” one official told him. “We are delivering services at the cost of our lives but we are unpaid for two months.” It was 12:50 am when we started our return from Chanpora. The minister was without security. It was literally terrifying to move around with him during the dead of the night when sloganeering had made Srinagar very noisy. The car was silent enough to hear what was being aired from the mike-fitted mosques. Thank God, nobody stopped the lone vehicle anywhere.

The visit, as I understood later, was necessitated after a newsman asked visiting members of a small all-party team to visit Chanpora and understand how paramilitary forces were behaving. It was at that point that a Delhi journalist (a female) disputed the report saying it was the propaganda by the vernacular media. Keen to hold the media responsible, all the members showed interest to visit Chanpora but the governor’s administration refused them permission. That day, George landed in Srinagar and spent a long time with his friend Dr FarooqAbdullah and finally decided to visit Chanpora personally. Vakil apparently had volunteered to arrange the meet because his newspaper had broken the story.

It was George’s first Kashmir visit after getting the Kashmir Affairs portfolio on March 11, 1990, in addition to the railway ministry, he already had. The Kashmir ministry was having an all-party advisory committee comprising seven members who were discussing the political inputs from Kashmir and various political parties and helping the minister to intervene on issues of importance. “His appointment was the outcome of the then Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s loss of moral authority in wake of the abduction of his daughter, Rubiya Sayeed, and the negotiations that followed which resulted in bartering her freedom with the release of militants,” one person who was close to Mufti throughout said, insisting he had personally told him. “George was already involved in Kashmir so the ministry went to him.”

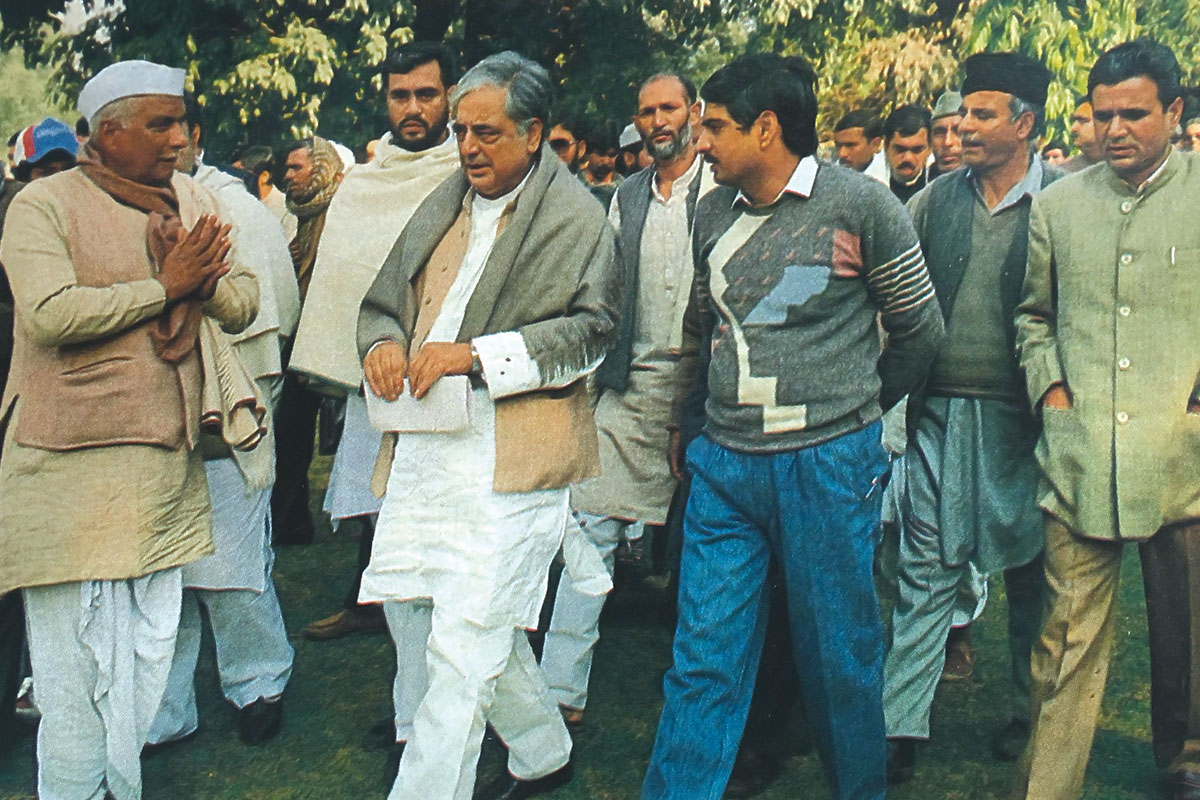

Like the old comrades, he would fly to Srinagar, sit in the Railway Home at Tulsi Bagh and move around, talk to people. Some of the officers in the state government, especially Ashok Jaitely were very close to him and that was the source of his cutting edge information on Kashmir. “He was the person who lent his ear to the people in Kashmir in the most difficult times of history,” former minister, Naeem Akhter, who was into employee activism in the 1990s, said. “His major contribution was to ensure an uninterrupted supply of medicines at a time when the hospitals here were literally buried under casualties on daily basis.”

“I am told he was meeting a lot of people,” Yousuf Jameel, the most known Kashmiri journalist in 1990s said. He would even visit jails to talk to people. “One day, he rang me up and invited me for a meeting but I told him, it was not possible because of the situation. He did not insist further.” Jameel said George was very pushy in helping a few thousand HMT employees to get their salaries released. HMT watch factory at Zainakote had closed because of the technology deficit and the employees were literally on roads to get their salaries.

“George was convinced that the central government departments were not recruiting the majority community candidates fairly,” Akhter said. “He initiated a process and more than 1000 young men from Kashmir were recruited on basis of merit and not on Sufarsih.”

George’s Kashmir activism was disliked by many, especially the right-wing BJP. Some even believe that his frequent interventions were creating a parallel power centre to the Raj Bhawan, then manned by Jagmohan.

“When George Fernandes was appointed as special minister, specifically to revive the political process in the state, and he quickly put together a parallel administration, the exercise was seen as a calculated insult to the Mufti and a reflection on his and his nominee’s (Jagmohan’s) competence to handle the emergency in Jammu and Kashmir,” Vinod Mehta commented in Sunday (May 6-20, 1990) magazine. “There were reports that the home minister was contemplating resigning and by all reliable accounts, he was very close to quit. We are told he was advised not to press his resignation in the “the national interests”. What a pity. The Mufti would have served the national interest better if he had pressed.”

George interventions triggered a serious crisis within the governance systems. Jagmohan, the then governor, has very negatively commented on him. In his My Frozen Turbulences in Kashmir, Jagmohan has recorded that he had explained George his plan (see page 462) about eliminating Pro Pakistan and hard-core fundamentalists” so that other elements could be won over. But after the formation of the committee “undermined my position”, George changed and started working “independently, scrumptiously and even at cross-purpose” and “presented me as a hardliner and an uncompromising Hindu chauvinist”.

Jagmohan believed George’s approach (see page 465) was “impractical, unrealistic and even self-contradictory”. He insisted that a friend of Dr Farooq Abdullah (see page 466) cannot cultivate elements “whose suspicion was aroused by the very mention of the name of Dr Farooq”.

Conceptually, Jagmohan’s adviser Ved Marwah wrote in his Uncivil Wars: Pathology of Terrorism In India, the policy of a multi-prong approach to finding a solution to the Kashmir problem, was quite sound. “The governor could have concentrated on dealing with the administration and security matters, and the political side could be left to George Fernandes and the advisory committee,” he wrote (see page 94). “The experiment, however, could not work. It could have worked only if George Fernandes and Jagmohan have been able to work together as a team and that was impossible since the minister of Kashmir affairs and the governor were not over-fond of each other. Each held the other in contempt and responsible for the “mess” in Kashmir. One fallout of this dual policy was a division in the bureaucracy. One group was strongly pro-Fernandes while the other was pro-Jagmohan.”

On May 9, 1990, George visited the Aligarh Muslim University and made a long speech that also included Kashmir. This upset Jagmohan after the excerpts of the speech was highlighted by the Kashmir media. Eventually, he wrote a letter of protest to the Home Ministry on May 16. That actually marked the beginning of his undoing.

“When it became evident that the Governor was messing up things in the Valley, several heavyweights in the union ministry, notably George Fernandes, who was given additional charge of Kashmir affairs, lobbied for Jagmohan’s removal,” Shiraz Sidhva, then one of the well-informed reporters, wrote in Sunday magazine (June 3-9, 1990). “And Fernandes had every reason to see Governor’s ouster. Jagmohan, it may be recalled, did not even allow George Fernandes to visit Kashmir and made things difficult for the minister.”

Within days after his appointment, George was unhappy with the assignment. By the end of March, he had sent his report to the VP Singh government making a set of suggestions to improve the situation. “The BJP opposed the Left idea that there has to be some political intervention,” al-Safa News reported on March 28, 1990. “As there was no action on his report, he felt disinterested and stopped even visiting Kashmir and indicated he would resign.”

“One reason why the Prime Minister did not remove Jagmohan was due to the fact that though the Governor was hated by Kashmiris, he enjoyed the support of most people outside Kashmir. And the Hindus of the Valley looked upon Jagmohan as their saviour, ”Sidhva reported. “But the greatest hurdle was the BJP. Individuals from the government were meeting the BJP seeking their views about Jagmohan. They were assured they would not remove him. Prime Minister was waiting for the opportune time to “drop the axe”. He did not want the militants to get an impression that “centre was giving in to their demands”.

The opportunity came to Delhi but at a huge cost to Kashmir. Within days after Mirwaiz Molvi Farooq was assassinated and in quick succession, his funeral procession was also fired upon by BSF – his dead body also received a number of bullets – on May 21, Jagmohan was sacked. A S Dulat, the Intelligence Burea sleuth who eventually became the RAW chief in his book Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years has said that militants killed the cleric because he was in touch with Fernandes. “He was assassinated by Hizbul Mujahideen gunman Mohammad Abdullah Bungroo because he was in touch with National Front railway minister George Fernandes; the militants bumped off several people they suspected to be parleying with Delhi in those days,” he wrote.

“Even the Governor’s staunch supporters in the union cabinet – Arun Nehru, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed and Arif Mohammad Khan – could do little to save Jagmohan after paramilitary forces gunned down 60 mourners during Mirwiaz Farooq’s funeral,” Sidhva reported. Garesh Chander Saxena replaced him. Despite being in-charge minister for Kashmir, George was not even consulted as he was in Cairo. He was taken aback by the developments.

But with Jagmohan, George also went. “After returning to Delhi, George Fernandes was all set to visit the valley when the minister received a call from the Prime Minister asking him to speak to home minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed immediately,” according to Sidhva. “Fernandes rushed to the Mufti’s residence only to learn that the Home Minister was closeted with V P Singh. Later the Prime Minister rang up Fernandes again and told him that it would be a good idea to wind up the special cell on Kashmir since the BJP’s Kedar Nath Sahni had already withdrawn from the body in protest against Jagmohan’s dismissal.”

Even though Jagmohan’s sacking indicated that Delhi was not supportive of the harsh systems in Kashmir, George’s ouster indicated it did not want a political way-out either. Eventually, it was the state’s military power that ran the roost with politics nowhere around. “Whatever little the government gained by removing Jagmohan was frittered away after George Fernandes was relieved of the special charge of Kashmir,” Sidhva reported. “Whatever the detractors might say, George Fernandes was one leader who was acceptable to the Kashmiris and his ouster at this crucial stage will cut off the people in the valley from New Delhi. More important, the efforts to revive political activity in the state will in all probability be dropped. Simply because there is no one after George Fernandes to attempt the bold experiment”.

It took five more years and a lot of bloodletting that somehow a civil government was put in place after a highly questionable electoral process in which the security grid would coerce people out of homes to the polling booths. By March 1998, George was India’s Defence Minister and that linked him to Kashmir directly. Kashmir was being ruled by his friend Dr Farooq Abdullah with an absolute majority.

Exactly a month after his takeover as Defence Minister, the Rashtriya Rifles (RR) engaged in a fierce 97-hours long encounter in Aahgam that ended on April 19, 1998. The village that literally means – a village of sighs – is located on the border between Shopian and Pulwama districts and was reduced to a ruin. As many as 20 homes went up in flames and 36 were hugely but partially damaged. Besides, 31 cowsheds, 12 grain-houses and three kitchens were also part of the “collateral” damage. People started living under open sky till the officials managed some tents and some cash for them to restart the life afresh.

The death toll was also huge: though a number of militants managed to give a slip to the RR, still seven militants were killed: Abdul Haq (Rishnagri Shopian), Owais Karni (Bahawal nagar), Badshah Khan (Sarhad, Pakistan), Aadil (Lahore), Naoman Sheikh (Faisalabad), Souban Hizbi and Major Ali (Gujarat, Pakistan). Three army men – Baldev Singh, Hawaldar Amarjit Singh and Lance Naik Prahlad Singh, besides two cops, lost their lives in the operation. Seven soldiers and eight civilians survived injured. Almost a complete herd was roasted alive.

The story of the police duo was tragically interesting. Selection Grade Constable Ghulam Mohammad and an SPO Tariq Ahmad had actually walked into the death knell. They were part of the security detail of a Communist leader in Poshpora, located at a safer distance from Aahgam. On April 14, when the counter-insurgency grid was chasing dozen-member militant group, the duo started hunting for some medicine for their ailing colleague. Neither they could get it from Poshpora nor in Hawl so they proceeded towards Nazimpora. Since the militants knew they are being chased, the two cops seeking medicine for their colleague fell into rebel trap. They were kidnapped and were being held as a hostage when the operation was launched. Two days after the conclusion of the operation, their bullet-ridden bodies were recovered from Sheikh pora, near a brook.

This was one of the worst encounters in Kashmir. After the operation was over, the “conflict visitors” started arriving, some with help and so many to see what actually had happened. An Aarihal family went to see the village and when they returned home, their six-year-old boy was carrying a “toy”. It eventually proved to be the device that troops using as illuminator during nights. It exploded leaving the entire family of five injured.

The extensive coverage of the devastating operation created a serious public relation crisis for the army. The intelligence specific operation was termed the most unintelligent one. Almost everybody flew to visit the village: the Chief Minister, Home Minister and Congress President Sonia Gandhi (see Times of India, May 25, 1998). With Major General R K Kaushal at the helm in Victor Force, the army quickly decided to convert the crisis into a sort of an opportunity.

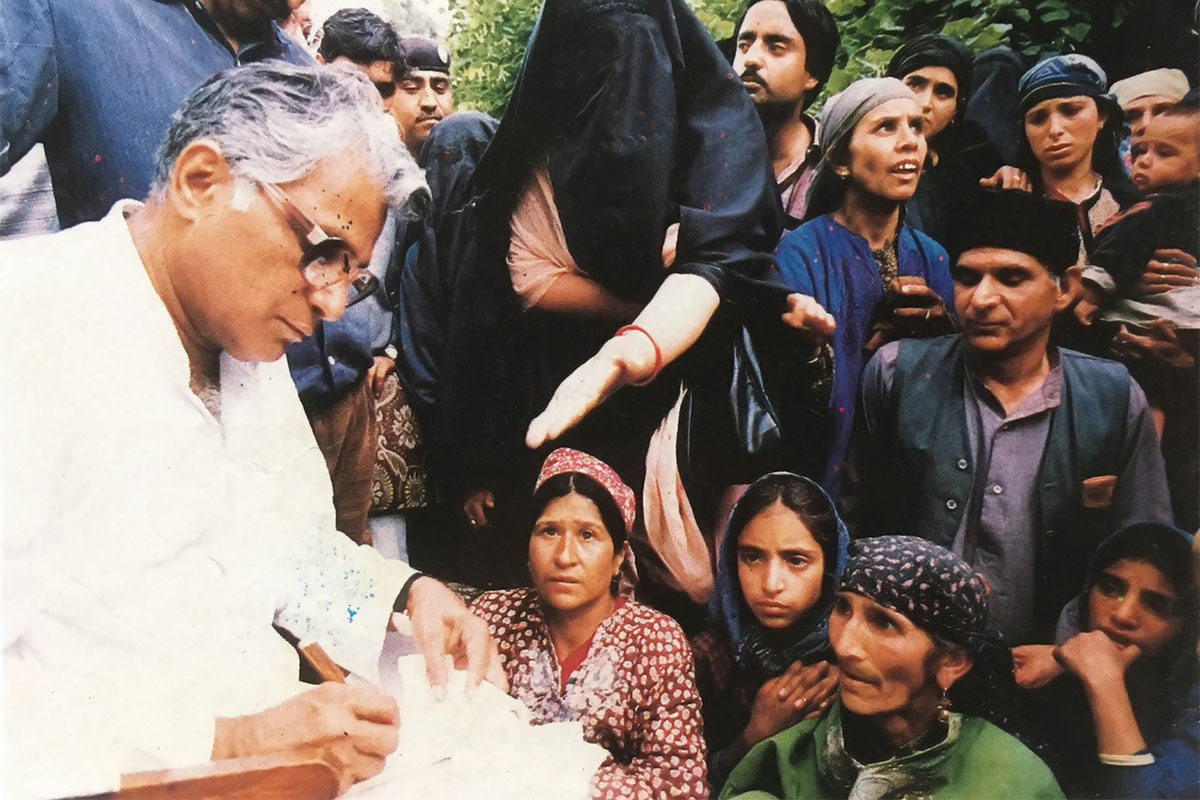

On April 30, when Defence Minister George Fernandes landed in the neighbouring fields and visited the village, he saw three companies of the engineering regiment working, clearing the debris and busy raising tin-sheds for the affected families. Interacting with the residents, he assured them all help in reconstruction and rehabilitation. “I am not coming to Kashmir for the first time, I have recruited more than 600 youth in Railways,” George told the residents. “I seek your cooperation to get peace back.”

Much later, it was clearly known that the much talked about Operation Sadhbhavna was actually launched from this village. In November 1998, the army told Kashmir Times (see November 24, 1998) that they had paved three streets of 2100 meters of length and dedicated it to the memory of the slain soldier trio. They had set up a school, repaired local PanchayatGhar, and renovated a park at an investment of Rs 5.30 lakh.

In fact, helping the village to rehabilitate became a moment, cutting across party lines. While the state government extended some help per family, the Hurriyat Conference also contributed a small amount. Sonia flew from Delhi with a million rupees bank cheque as well.

Since then, the village has doubled its population. Nobody knows how long the “operation” was sustained. But the operation that George Fernandes launched still survives across the state. Details in public domain suggest the army has spent almost Rs 450 crore on the Operation Sadhbhavnaso far.

George retained his ministry in 2001, that helped him to emerge perhaps India’s first Defence Minister who created a record of sorts by visiting Siachin Glacier 18 times. His tenure remained plagued for one or the other racket, before and after the Kargil war. The contradictions were visible.

“During Operation Parakram, Army chief Gen S Padmanabhan would plead with him about letting the Army cross the border to avenge the attack on Parliament and end a decade of cross LoC violence and indignities in Kashmir,” General Ashok K Mehta wrote in the Print. “But George was not swayed.”

“Fernandes had ordered the Army to conduct a top-secret raid across the Line of Control that till today remains the only one that completely achieved its political-military objectives,” journalist Menvendra Singh wrote in the Wire. “It was never reported in the Indian media. There were reports in the Pakistani media, but those have now been taken down.”

Despite knowing the ground realities in Kashmir and the massive spread of the armed forces operating under sweeping laws, George barely intervened. Akhter said he supported the state in getting clearance from his ministry for the introduction of mobile telephony.

However, his intervention in the arrest of journalist Iftikhar Gilani case was crucial. A Kashmir Times journalist, Gilani was arrested from his Delhi residence in June 2002, and a case under Official Secrets Act was slapped against him. As the home ministry was giving turns and twists to the case amid a media trial, it eventually required authenticity to a document forged enough to make it highly confidential. The authentication was supposed to come from defence ministry and that is where George advised a top Military Intelligence officer to depose before the trial court. That marked undoing to the fabrication creating a situation that the MHA worked on a holiday to draft its plea to withdraw the case.

“George Fernandes had not only helped immensely in restoring my freedom but also sought to give a healing touch after my release,” Gilani wrote in his hugely read and massively translated My Diary In Prison (see page 121). “He invited my family and me to spend some time with him on republic day. He cancelled his attendance at the president’s reception just to spend time talking to me before I left for Jammu to personally thank everybody at the Kashmir Times.”

Instead of getting into his army’s battle order in Kashmir, George tried intervening on the other front. He attempted linkage of local industry in Jammu and Kashmir with the armed forces, an initiative that was not sustained later.

In 2000, George presided over “novel” buyer-seller meetings – in April at Jammu and in October in Srinagar, in which the local industry displayed the items they manufacturer for the requirement of the armed forces. The first meeting witnessed the participation of 180 manufacturers, which jumped to 185 in the second meet. In a follow-up to the first meeting, a 10-member task force was constituted to explore the possibilities of future of the exercise, to identify potential items and make recommendations. The report that George released personally in Srinagar had identified 25 items manufactured by various industries in Jammu and Kashmir. Items that were literally approved for supply to the northern command included wooden ammunition boxes, blankets, one lakh poultry birds a month, a winter heater that Kashmir has standardised, walnuts and some uniform stitching jobs.

“This is not just business alone,” Omer Abdullah, then India’s Jr Commerce and Industries minister said. “The aim is the economic integration”. Nearly two decades later, everybody in Srinagar knows, no order came to any Kashmir unit ever. A lot of ammunition was fired but no box was procured ever.