It took a long time to undo the government’s monopoly over the printing press. Scholar Nayeem Showkat details the evolution of the printing facility and allied newspaper sector in Jammu and Kashmir since 1858

Four centuries past the invention of Gutenberg’s press, dotted by fervent production of information, the Dogra rulers of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir acquired their first printing press Vidya Vilas Press in 1858. Its purpose was the printing official documents in Jammu. The press was equipped with facilities to also print Persian and Devnagri script and it has published several books as well.

Pandit Bankat Ram Shastri from Banaras is said to be instrumental in helping the Maharaja in the establishment of the press. Meanwhile, Saligram Press was also established in the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir. It is noteworthy that both the presses were endowed with the technology to print Urdu script as well, and as mentioned in Akhtar Shehanshahi, these facilities were cardinal for the birth of Urdu journalism in Jammu and Srinagar.

Translation Department

Roping in various eminent scholars under the supervision of Pandit Govind Koul, Maharaja Ranbir Singh, concurrently, established a translation department to translate books from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian and English into Dogri, Urdu and Hindi. The books encompassing extensive areas of astronomy, geology, mathematics, physics, zoology, and chemistry, were printed for free distribution to scholars of government schools, pathshalas and madrasas.

With aforethought of higher studies in oriental languages, schools were instituted in every wazarat and tehsil, with two such principal pathshalas in Raghunath Temple, Jammu, and Utterbhani respectively, imparting instructions in Vedas, grammar, Kavya Shastra and Nyay. For the accomplishment of the desired goals, books were supplied free of cost, and scholarships were granted to the scholars and teachers.

Besides, Maharaja Ranbir Singh also constituted a body of scholars in view of the translation of shahparas (writings) of various languages into Urdu and Hindi, which triggered debates on their critical and historical context. The rationale behind his intention of floating an organisation called Vidya Vilas Sabha, was to bring together various intellectuals and literati as its members, to discuss and debate different literary issues for the promotion of various languages including Sanskrit, Persian, Hindi, Dogri and Urdu.

It was in that era that numerous manuscripts of Sanskrit and Persian were printed and translated into Dogri, Hindi, and Urdu. It is worth mentioning that a substantial number of texts written in the Sarada script of Kashmiri were transcribed into Devanagari. The library then consisted of around 5000 manuscript volumes, some of which were printed in Vidya Vilas Press.

The News Media

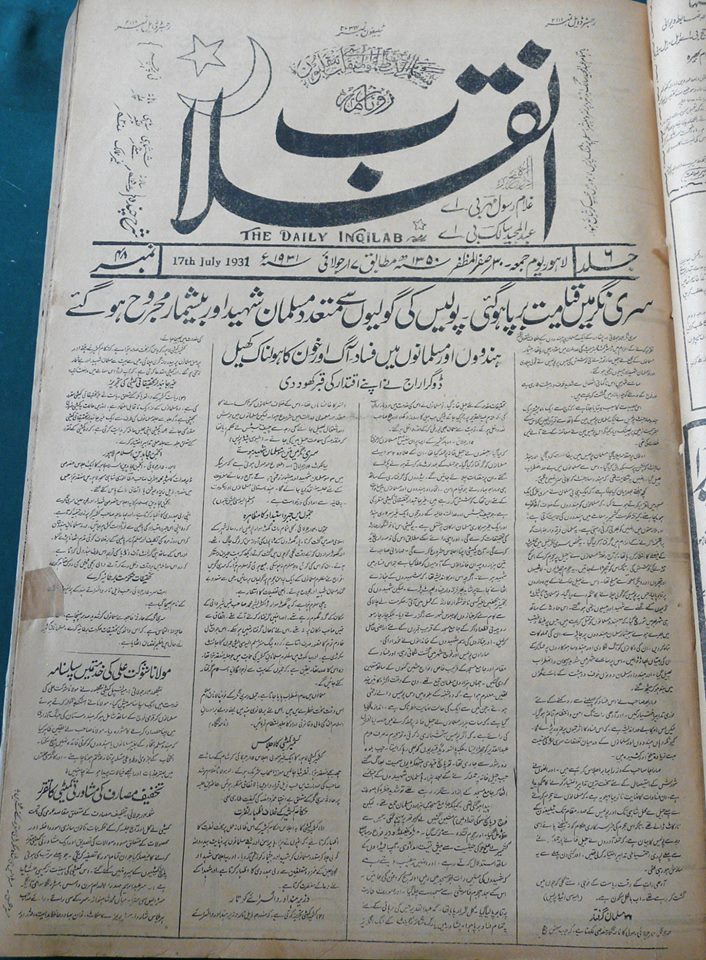

The watershed moment in the history of news media in Jammu and Kashmir came when Vidya Vilas Sabha started to publish a double-column bilingual – Urdu and Hindi (Devnagari script) – a weekly newspaper, Vidya Vilas Jammu, covering the proceedings of this sabha. This laid the foundation of the first-ever newspaper of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir.

However, according to the First Press Commission Report, an independent periodical namely Vrittanta Bilas was published from Jammu in 1867. Surprisingly, no evidence could be found to further substantiate it.

The reference of Vidya Vilas is found in Savaaneh Umri Akhbarat, which was published in June 1896 with the name of Akhtar Shehanshahi from Lucknow by Akhtar u Daula Haji Sayed Mohammad Ashraf Naqvi. The newspaper is said to have been started by Maharaja Ranbir Singh at the suggestion of Munshi Harsukh Rai, the editor of a Lahore-based popular Urdu newspaper Kohi-i-Noor.

Published from Vidya Vilas Press, Jammu, this newspaper came into existence in 1867. In contradiction with other writers, DC Sharma claims the year of its publication to be 1868.

Growing up in the shade of the palace, this weekly newspaper contained eight pages. However, according to Tahir Masood, the newspaper comprised 16 pages. The news on its right column used Urdu script and the left column had Devnagari script.

Most historians have referred to this news sheet as Bidya Bilas. It is notable that both the Hindi words Vidya and Vilas denote The Luxury of Knowledge. However, the word Bidya is the same in Urdu as Vidya, while no such word called Bilas exists in either Urdu or Hindi language.

It raises certain doubts regarding the usage of these words either due to the local parlance or it could have simply been a mistake of an inscription. So, the title of the newspaper may be written as either Vidya Vilas or Bidya Vilas.

With a subscription rate of 12 rupees per annum, the newspaper was published every Saturday. Khojo Shah Sadrullah was the manager, while Bakshi Krishan Dayal was the editor of the weekly. According to Akhtar Shehanshahi, Maharaja himself was the patron, with Pandit Bankat Ram as its owner.

Maharaj Ganj Press

Following his ardent interest in the development of the Urdu language, Deewan Kripa Ram recommended Munshi Harsukh Rai of Koh-i-Noor to establish a private Urdu printing press in Srinagar, also promising to offer him certain facilities for it. Consequentially, in response to the offer, came to the fore the printing press Tohfa-e-Kashmir, which was established by Rai in Sheikh Bagh Maharaj Ganj area of Srinagar in 1875.

The press brought out a weekly newspaper with the same name, Tohfa-e-Kashmir from Maharaj Ganj the next year. This is said to be the first newspaper ever published from the province of Kashmir, though the practice couldn’t sustain for long. It is the same press where Abdul Salam Rafiqi’s weekly Al-Rafiq was printed in 1896.

The periodical’s critical approach, however, led to its closure as well as that of the printing press Tohfa-e-Kashmir Press. Rafiqi, later on, is said to have published the newspaper from Rangoon. However, the claim of certain historians that Rafiqi resumed publication of this newspaper from Rangoon in 1906 with the support of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in Aligarh looks dubious as Sir Syed had died in 1898.

Further, the development of the printing press received a major setback when Muhammad Din Fauq submitted an application in 1904 seeking permission to initiate a newspaper from Srinagar. This request evoked an opposite reaction with the prime minister issuing a command for the formulation of a decree banning the setting up of a printing press. It was the time when the Moravian Mission under the leadership of Father FA Red Solob as the superintendent had already instituted a litho-press with an aim to publish the translated books in its Leh office.

Ranbir Takes Off

With no visible impact of the invention of the printing press five centuries ago on the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir, the press here took a long to set in motion and develop. It was on March 27, 1924, Mulk Raj Saraf was conveyed the State Council’s order permitting the initiation of a newspaper in lieu of cash security of Rs 500 as laid down in the Jammu and Kashmir State Press and Publications Regulation Samvat 1971. Besides issuing a newspaper Ranbir, he was granted permission for initiating a printing press in Jammu under section 5 of the Act.

However, with no clue about the printing press, Saraf on his query was apprised by the establishment that “the permission to a newspaper implied the starting of a press as well.” Maharaja also agreed to donate Rs 50 per year to Ranbir. Thus began the journey of the State’s first regular Urdu weekly Ranbir. Saraf in his autobiography claims to have initially thought to name his newspaper Pahari and printing press Dogra Press in place of Ranbir and Public Printing Press respectively.

The office of Ranbir was set up in Thakur Kartar Singh’s cutcha quarter near Rani Talab. Unable to afford a power-driven plant, a hand-driven litho printing machine was installed for printing Ranbir.

Besides that, owing to the lack of katibs (calligraphists) and machine men in Jammu and Kashmir, a government katib Munshi Taj Din assumed the job of calligraphist on the condition that the necessary material be supplied to him at his home instead of him coming to Ranbir’s office.

A Government Monopoly

It is noteworthy that the government had a complete monopoly on the printing press till that time. All the earlier Census reports including the report of 1911 were silent on the inception or existence of printing presses or periodicals in the State.

For the first time, it was only the Census report of 1921, which mapped the printing presses prevalent in the State of Jammu and Kashmir. The Census report of 1921 mentions a total of four printing presses in the industry of luxury category. Revealing that no private printing press remained in existence, all the printing presses have been specified as ‘Government of Local Authority’.

It is recorded that one printing press was installed in Jammu, one in the central jail, and the remaining two litho presses also in central jails. The report further delineates that there was a printing press in the Jammu district employing 165 people including one direction manager, one supervising and technical staff, 17 clerks, 133 skilled workmen and 13 unskilled labourers.

One printing press called Printing Press (Jail) was also functioning in the Jammu district employing 31 workers including supervising and technical staff, two clerks, eight skilled workmen and 18 unskilled labourers. Similarly, there were two printing presses (jail) in Kashmir South, hiring 116 employees including four supervising and technical staff, two clerks, 37 skilled workmen and 73 unskilled labourers.

The Glancy Commission

In light of a paradigm shift across the world, Maharaja Hari Singh eventually accepted Glancy Commission’s suggestions and repealed the Jammu and Kashmir State Press and Publications Regulation Samvat 1971 on April 25, 1932. A new act, Jammu and Kashmir State Press and Publications Act Samvat 1989 came into force on the same day.

Largely on the lines of a similar law in vogue in British India, this Act liberalised the press in Jammu and Kashmir. This ‘gambit’ of Maharaja Hari Singh to liberalise the press in the princely State was not only lauded in the territory but across British India. The new Act legitimised publication of dozens of newspapers since May 1932.

Within a demi-decade of the enforcement of the new Act, a spurt in publication rate was witnessed in Jammu and Kashmir, subsequently resulting in the birth of several dozen newspapers. It is estimated that the number of newspapers increased to three dozen by the end of 1937.

According to the Census of India, 1941, the Indian union had some 3,900 newspapers including 300 dailies and 3,600 others, with a cumulative circulation of seven million. However, according to the Report, there were 44 newspapers in the State in the spring of 1941.

The document reveals that the growth of newspapers during the period

(1931 to 1941) in Jammu and Kashmir was significant. In 1931, Jammu province had only one newspaper, and Kashmir province had none. However, in 1941, Jammu province had 24 newspapers, and Kashmir had 20 newspapers, making a total of 44 newspapers in the state. Interestingly, the report also mentions that Frontier districts did not have

any newspapers until 1941, as indicated in the Census document.

Proclaiming that a fair number of such newspapers were issued punctually and regularly, the census data further revealed that while a portion of it couldn’t last long, others were published at uncertain intervals. The Census discloses that local newspapers were mostly printed in Persian (Urdu) script; a few were also printed in English (Roman) and Hindi (Devanagiri) script.

Though expounding that the standard of journalism has improved like never before, yet the Census data divulges that the influx of newspapers at that time was so high for a minimal newspaper-reading public that most of such newspapers would hover between life and death.

Surprisingly, the Census of India 1941 betrays that the first printing press in

Jammu and Kashmir was installed in 1912. It further documents the growth of

printing presses between 1931 and 1941, stating that in 1931, State of Jammu

and Kashmir had eight printing presses, with four installed in Jammu province

and four in Kashmir province.

In 1941, the number of printing presses in the State of Jammu and Kashmir had

increased to 37, as per the Census of India report. Of these, 22 printing

presses were present in Jammu province, while 15 in Kashmir. Needless to say,

the Frontier districts remained without any printing press during both the time

intervals discussed.

Text Books

The Census Report of 1941 notes that information about the publication of non-

educational books in Jammu and Kashmir is mostly unknown. Albeit, it

highlights that the number of non-educational books was small but increasing in

the region.

No textbook, according to an official document, was printed in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir till 1936. It was during Maharaja Hari Singh’s reign only that the textbook business was nationalised in the late 1940s. To ensure prompt publication of the approved manuscripts, and further accelerate the process of printing in the State, the services of all the private presses were rendered.

The opulence of this milieu, armed with the freedom of expression, was further reinforced with various other platforms of generating public opinion like sabhas and societies set in motion. The Census of India betrays that a total of 435 sabhas and societies had been instituted in the princely State till the spring of 1941.

Since then, some of those itemised would perhaps have become obsolete whereas others may have emerged. Of these, 125 were classified as social, 258 as religious and 52 as political in nature.

It was the time when a foreign electronic printing machine from Lahore was also imported to Kashmir in 1932 along with an experienced machine-man namely Pandit Balik Ram for Ranbir. In 1943, Saraf purchased new machinery for his printing press – which was later named Prem Printing Press – for the purpose of enabling it to print English, Urdu, Hindi, Sanskrit, etc. An adequate number of newspapers from Jammu were now published at Prem Printing Press.

Post Partition Era

As a result, the literary activities in Jammu and Kashmir were further enhanced with the literati starting book shops and printing presses for the mass dissemination of literature across the length and breadth of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir.

Further, in an attempt to modernise the printing presses, the government of Jammu and Kashmir led by Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah installed new machinery in the government presses in the State. The presses were developed under a three-year plan and a team of officers was sent to visit the presses in other parts of India.

The government also intended to send some students to England for getting the requisite training in handling the modern printing press. The machinery costing Rs 94,000 was procured for Srinagar, while Rs 50,000 for Jammu.

These decisions were taken at a time when Kashmir had many printing facilities, up and running: Brokas Press, Nishat Press, Srinagar, Clifton Press, Srinagar, Guru Nanak Printing Press, Srinagar, New Kashmir Printing Press, Commercial Printing Press, Srinagar, to name a few.

However, it seems that the events that unfolded in the backdrop of partition had an impact on the press and printing industry of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir to the extent that the whole printing industry was back to square one.

Owing to the topography of Jammu and Kashmir and only a few printing presses in place, it is conspicuous from the Census report of 1961 that the state couldn’t progress much in the field of printing. So was the condition of those minuscule presses that most of the printing work of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir was outsourced to Aligarh Press. It was still the government press in Jammu and Kashmir which was well equipped, but not to the extent that it could handle large consignments.

A Grim Situation

The situation in the erstwhile State remained quite unchanged even two decades after partition. As is evident from the Report of the Enquiry Committee on Small Newspapers, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, New Delhi, 1965, the periodicals in Jammu and Kashmir mostly don’t own the premises housing the periodical.

Besides, the equipment used by the majority of the newspapers also doesn’t belong to them. It was also revealed that the majority of the press undertook works other than printing newspapers to sustain itself.

It came to the fore that a major chunk of newspapers in Jammu and Kashmir had no printing facilities of their own and used to print their newspapers at other presses. To much surprise, it was found that not a single newspaper in Jammu and Kashmir had subscribed to any news agency at that time.

Further, according to the report most of the newspapers in the State were not illustrated at all. It is remarkable that no newspaper in Jammu and Kashmir had its own block-making facility. The newspapermen in Jammu and Kashmir were of the opinion that a financial corporation should be established which would grant loans to newspapers for the purchase of printing presses and equipment.

One of the major concerns of the newspaper industry at that time was the lack of good printing presses in the erstwhile State. The report also unveils that otherwise obsolete and out-of-fashion litho presses were ubiquitous in Jammu and Kashmir.

The output of these presses was as little as 600-700 copies an hour. During the Committee’s visit to two printing presses in Srinagar, it was also revealed that most of the presses were installed on premises which were unsanitary.

The newspapers were informed by the Committee that since the government had taken some steps to facilitate the printing of certain newspapers at the government presses, yet owing to newspapers’ failure of paying the printing charges, the experiment failed.

With an intent to avail printing facilities at economical rates, the Committee was told by the publishers of various newspapers that the government should consider the establishment of printing estates on the lines of industrial estates.

The Calligraphists

Not only the lack of efficient printing presses but also the printing of Urdu script through the litho process was impossible without the help katib (scribe). It is noteworthy that Urdu newspapers had a monopoly in the media industry of Jammu and Kashmir.

So, there was an unprecedented demand for katibs, who were employed on a salary as well as a job-rate basis, with the development of the press in Jammu and Kashmir. The getup of a newspaper relied completely on a katib.

As per the recommendations of the Enquiry Committee on Small Newspapers, the katibs were to be provided training in Polytechnic Schools so as to standardise Urdu calligraphy. This recommendation was further supplemented with a note by Hayat Ullah Ansari, according to whom Urdu calligraphy was standardised centuries back, that instead of the breadth of the nib as a unit to fix the dimensions of letters, the measurement of graph paper should be used so that writings of different katibs would look similar.

Ansari also suggested some changes, particularly in joints of the letters, like meem goes so much down that it occupies upon the second line and in the same way markaz goes so high that it touches the upper line. These changes would further improve the quality of Urdu writing and will save much space, he suggested.

What made the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir quite a peculiar case in this regard is that no school for katibs was established in the erstwhile State or in any other neighbouring state, thereby resulting in numerous printing faults arising from the low efficiency of katibs as was observed by the Committee.

(The writer is a Post-doctoral Fellow in Media Studies at the Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi.)