A Bengal Medical Service professional, G C Ross spent some time in Kashmir in 1877. He wrote a couple of write-ups about the life, amenities and governance in the valley, a year later. The following essay describes a general situation of Kashmir governance with a focus on the Srinagar city

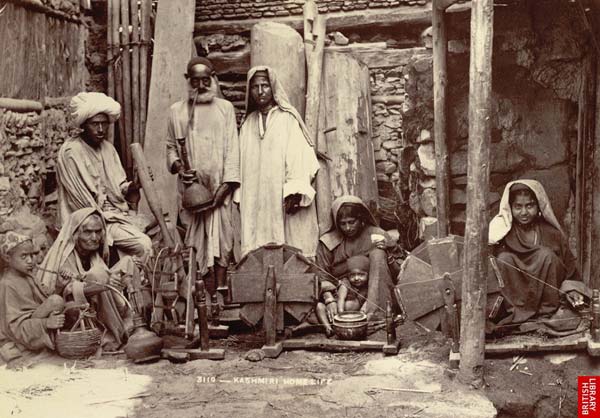

The Kashmiris are a remarkably handsome and physically robust race. Their physique, character and language form a very marked contrast to the rest of the races of British India.

Kashmir’s proper may be divided into Mahomedans and the Pundits, who are the Hindu remainder, who have escaped conversion into Mahomedanism. They are all Brahmans.

The Mahomedans are divided into several classes – the boatmen Hanjies, shawl weavers, goldsmiths, metal workers, &c.; there is also the Batul (could be Vatul) caste, which is probably a non-Aryan aboriginal relic. They are the workers in leather, musicians and nautch girls.

The Mahomedans and Hindus are an Aryan race of light complexion, robust and handsome.

The clothing consists of a long loose gown, made of home-spun wool, short pyjamas and a skull cap with turban. Coolies and shikaries wear a cummerband and knickerbockers with putties – bandages – round the leg. The ordinary shoe is worn in the towns, and in the country grass chupplies made of rice straw.

Every Kashmiri, no matter what age, condition, or sex, carries about in the cold weather a portable stove, called a kangri. This is a small earthen pot enclosed in wickerwork, with a handle and filled with charcoal; they slip one arm inside out of its sleeve and hold the kangri underneath their great loose gowns, then squat down. This arrangement is very efficacious, but productive of severe burns and epithelioma.

Their character is very pronounced, but Englishmen only come across the trade and servant class who are notoriously liars, cowards and noisy. Yet they are cheerful, hard-working, very intelligent, excellent servants and clever at handicrafts, and as mountaineers the villagers and shikaries are probably unequalled.

In connection with the races of Kashmir the Dogra and Sikh must be mentioned, who form the soldiery. There is also another foreign element, although somewhat blended, a Durani-Pathan settlement in one of the valleys – Machipura.

The hills are grazed upon by the flocks and herds of the race of Gujers, who exist here as well as in other parts of India.

Language: The language is peculiar to Kashmir. It contains Sanscrit to the amount of twenty-five words in one hundred, forty being Persian, fifteen Hindustani, ten Arabic, Thibetan, Turki, &c. It is marked by its uncouth rusticity, yet the people are eminently musical, the songs of the boatmen especially being extremely melodious.

Government: The Monarch is the ultimate court of appeal, and Kashmir is ruled by a Dewan or Governor, assisted by high officers of State – a Financial and Revenue Commissioner and an Accountant General. The Chief Court is presided over by a Judge assisted by a Naik. The jurisdiction of this Court is restricted to civil and criminal cases only, revenue suits going to the Governor. The different grades of Courts are – Tehsildars, 24; Wazirs or Deputy Commissioners, five, assisted by a Revenue and a Judicial Assistant, the City Court and the Sudder Adawlat.

The Tehsildar has 200 to 400 sepoys under him; the Thanadar 40 to 50. The Kardar, who keeps an account of the crops, is allotted a certain number of villages; the Mokaddam over each village, who keeps an account of the crops, with the Putwari, a Pundit. In each village there are one to 4 Shagdars, who watch the crops while growing, a Sargaul is over these Shagdars, one to every ten villages, a Hindu generally. And finally, a Trazadar, who weighs the grain and a Hurkara or Police constable, one to every twenty villages; he is over the Dums or policemen, one in each village, who are quartered on the inhabitants. The above is a sketch of the method of revenue collecting and general government.

Serious crimes are infrequent. Security of life and property is very remarkable throughout His Highness’s dominions. Capital punishment does not exist, there are two jails in Srinagar; the prisoners are employed mainly at husking rice, carpet-weaving, cotton cloth, &c. The scale of diet is one seer of rice with dhall and vegetables daily and meat once a week. The seer is one-fourth less than the British.

Education is restricted to Persian, Sanscrit and Arabic. Great ignorance and superstition exist.

Medical: There is a dispensary at Srinagar with two hospital assistants in it, educated at Lahore, but the people would not go to it, whereas the attendance at the Medical Mission is nearly 200 daily.

Postal: A post exists between Murree and Srinagar, half of the British charge for India being extracted, and one anna on each English or Europe letter.

Revenue is derived from all sources; no product being considered too insignificant, no person too poor to contribute to the State. It amounts now, it is said, to £400,000.

All land is the property of the ruler, three-fourths of the produce being appropriated by him; two-thirds taken in kind and one-third in money.

The Government share of grain where it is sold at Government rates. No cultivator is allowed to offer the produce of his farm at a lower rate, or often to sell it at all, until the Government corn has been sold.

In addition to the money taxes on the different grains, there is also another which is levied annually upon each house in the Dehat of from 4 to 20 annas. Of fruit three-fourths of the annual produce is taken by Government. There is an annual tax of one anna per head on sheep and goats, and from all villages producing over 500 kharwars of grains, two or three are taken annually and half their value returned in coin – one pony and one looi or home-spun blanket are also taken annually under the same conditions. For each milch cow half a seer of ghee is taken; from one to ten fowls are taken from each house, according to the number of its inhabitants.

In the Lidder and Wardwan, two-thirds of the honey produce are taken. Tame bees are kept by the zemindars there.

The produce of the waters also belongs to Government. The singara nut yields very large revenue, which is farmed out, and fishing without a license is prohibited. The reeds of the Anchar produce, it is said, 4,000 chilkies annually.

The stamp duty on shawls is 26 per cent of the estimated value. The import of wool is taxed, and a charge made upon every shop or workman connected with the manufacture of 37 per head.

All trades are taxed – butchers, bakers, boatmen, vendors of fowl, sweepers, public notaries, even the prostitutes. All Mahomedans pay taxes except the tailors; most of the necessaries of life are Government monopolies – salt, tea, kot (the aromatic costus), brick-making. 25 per cent ad-valorem is levied on all boats being built; even the wretched coolie impressed for the traveller’s baggage is mulcted one-half. A tax called ashgul is levied on the Mahomedans for the support of the Hindu priests, also during the cholera epidemic of 1867 a large revenue was made by the sale of charms.

These most oppressive restrictions and taxes are only imposed within the valley, from whence escape is impossible. If free exit was granted, it is probable most of the inhabitants would fly, as many have done. It is no wonder, therefore, that a great portion of the land is out of cultivation, and that famines occur in a country – an actual terrestrial paradise – blessed by bountiful nature with every advantage of water, soil and climate. In 1865 a severe famine occurred, and grain had to be imported from the arid Punjab.

Coinage: The coins in use are copper and silver. The value of the silver Chilki-rupee was fixed at 10 annas British, but by an edict of the Maharajah, in one day, the 15th October 1871, it was suddenly reduced to 8 annas, and a new coin issued worth 10 annas. No effort having been made to call in the old currency, by this unscrupulous policy the cost of restoring the debased coinage fell on the unfortunate people. The new Chilki is better than the old, which was nothing but washed copper. It bears the monogram JHS, introduced by Gulab Singh. The coins are fabricated by hard labour, are unequal, and not of equal weight. The pieces of battered copper called pice are never of the same relative value five days together.

The army consists of 20,000 men- 16 batteries, 2 Regiments of Cavalry, 24 Regiments of Infantry, one of Sappers and Miners, and Irregulars.

The army is mostly composed of Dogras and Punjabi Hindus, some Ghilgities and hill-men.

It drills well, and is not badly armed; a quantity of Sniders and Enfields having been presented by the English Government.

The revenue is principally collected by the soldiery. The pay is 9 chilkies a month, four being stopped for rations and equipment, but the men generally live in the villages at free quarters.

The fighting powers of the army are not great, they dread active service in the hills, and did not distinguish themselves in 1857 at Delhi for anything but looting.

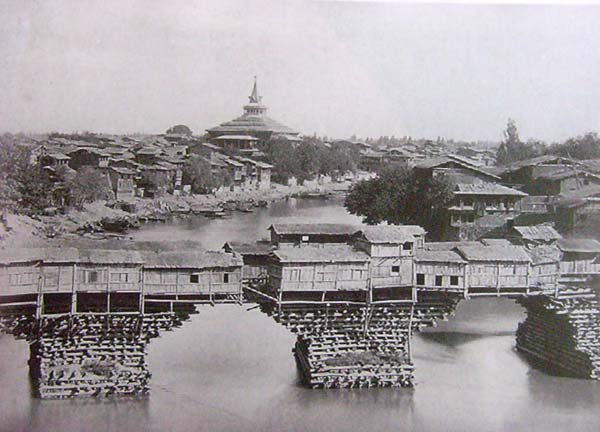

Srinagar: The town is built on a strip of dry land which stretches north and south, and is intersected by the Jhelum. On the outskirts, it is environed by shallow lakes and swamps. The Jhelum makes a long bend in its course through the town, and the latter is likewise intersected by numerous canals and water-courses.

The Hari-Parbat, an isolated hill crowned by a fort, dominates the city from its northeast corner, and it is likewise commanded from the southeast, at a distance of two miles, by another hill called the Takht-i-Sulaiman. The town extends for about three miles along both sides of the Jhelum, but is little more than a mile across at its broadest point; the greater portion is situated on the right bank.

The town has been likened to Venice from the intersecting canals and houses built sheer from the water’s edge.

Houses: These latter are chiefly constructed of bricks built up in frames of wood, the walls seldom exceeding a single brick in thickness. They are generally two and three stories high, and are mostly in a ruinous condition, with broken doors and shattered lattices, walls out of the perpendicular, and roofs threatening to fall; these last are made by layers of birch-bark covered with earth, which is again hidden by a vegetation of grass and flowers.

The houses of the better classes are commonly detached, and surrounded by a wall and garden communicating with a canal.

The general character of Srinagar is that of a confused mass of ill-favoured buildings forming a complicated labyrinth of narrow and dirty lanes, badly payed, and having a small gutter in the centre full of filth, banked up on each side by a border of mire.

Bazars: There are several bazars; that called the Maharaj Gunj, lately constructed, is a large quadrangle near the right bank above the 5th bridge.

City: The city is divided into twelve zillahs or parishes, each under the care of a Kotwal and a zilladar. These are sub-divided into mahullas, 277 in number – a minute division, and which would be of infinite use for sanitary arrangements.

The census taken in 1866 shewed:

Zillahs – 12

Mahullas – 277

Houses: 20,304

Shops: 1,037

Mohamedans 87770

Men – 44,356

Women..43,414

Hindus – 24857

Men – 13,292

Women – 11565

Total – 112,627

Trade is very limited, though the people are ingenious and industrious; probably, but for the European visitors, three-fourths of the population would starve, they being now almost the sole purchasers of the various articles of gold and silver, copper, iron, leather, &.c., produced.

River: The river is eighty yards wide, average depth 18 feet; an embankment of cut limestone formerly existed; this is nearly all destroyed.

Bridges are traditionally ascribed to the period of independent Mahomedan rule, from AD 1326-1587. They are thus constructed:

Piles are first driven to make a foundation; undressed deodar logs, 25 feet long and 2 ½ or 3 in girth, are laid about 2 feet apart horizontally, layer on layer; each alternate layer being at right angles to the one above it: in this way, the piers are raised to 25 or 30 feet. They are ninety feet apart, and are spanned by long poles, with a roadway.

The piers are protected by abutments of stones and piles. Some of these bridges are over 200 years old, and there are seven of them in Srinagar.

Canals: The river is supplemented by a network of canals, viz., the Kuth-i-Kol on the left bank; the Mar and the Rainwari with their branches on the right.

The Kuth-i-Kol leaves the river at the palace and then bifurcates; the western branch, the Sona Kol, is small and narrow, it skirts the town north-west and eventually empties itself into the Dudh Ganga, a small river running from the Pansal Range, and which joins the Jhelum below of the 7th bridge. The main branch goes northerly, passing by old siarats and gardens and empties into the Jhelum above that bridge. This canal is only navigable from April to July when the Jhelum is in flood, for the rest of the year it consists of’ fetid puddles.

On the right bank the Tsont-i-Kol or the Dol Canal leaves the river opposite the palace, it is there thirty yards wide and as deep as the Jhelum itself, and is always navigable; at the upper end it communicates with the Dal through flood gates which remain open only as long as the current sets from the lake, and when this condition is reversed, ie., when the Jhelum is in flood, they shut, so preventing inundations of the lower parts of the city. This canal is banked with splendid poplars, and the Chenar Bagh; in it may be seen myriads of ducks and geese (wild ones pinioned), the property of the Maharajah. The length of this canal is about one and a half-mile. A branch runs from the Water Gate southwards towards the Jhelum, but is stopped by an embankment at that end, it is, therefore, impassible except during heavy floods. This bounds the encamping grounds allotted to European visitors to the northeast, and is always a fetid, horrible nulla. Watergates to allow of flooding it would be very advantageous both as regards the health of the place, and as allowing a shortcut. If the canal was open without them, the Dal Gate would remain closed owing to the difference in level.

The network known as the Rainwari canals, runs from the Water Gate towards the city: it is joined by a small canal from the Cind river, originally intended by its constructor, Zein-ul-abdin, to supply the Jamma Masjid, and also by branches from the Dal lake, from whence a boat can go to the Anchar lake, passing the Dilawar Khan Bagh, the old place where Moorcroft, Henderson, Baron Hugel and Vigue were put up; it is a great route for market boats, most of the vegetable gardens existing at this side. These canals are crossed by very ancient bridges of single-pointed masonry arches. The most important branch called the Mar, or Snake canal, is navigable always except in November and December for large boats, and grain is brought by it into the heart of the city. A journey along it is very curious; it is narrow, its walls of massive stone, bridges, old ghats, ruins of temples supplying the materials, betoken great antiquity, and the lofty houses seeming to topple over, all form a very quaint and curious picture, but for the abominable stench arising from the filthy water, which quite destroys the idea of the picturesque.

Public Buildings: None of them are of any merit; the Jamma Masjid, a very large square Chinese-looking edifice, built by Shah Jehan; the Shah Hamudan Masjid of the same type, built by and named after a Syed who lived in the days of Timur-Lang – cir. 1360; the Ali Masjid built by Sultan Hussain, cir. 1471. These mosques are constructed of masonry and splendid deodar.

There is a fine old ruined mosque built by the tutor of Jehangir, on the side of the Hari Parbat Hill, with marble pillars and gates, all in a state of destruction. And near it the shrine of Shah Hamzeh.

The No Masjid was built by the Light of the world, Nur Jehan, but on account of her sex, though the finest building in Srinagar, is not used for devotional purposes.

The Bulbul Lankar is said to be the first mosque built in Kashmir, and to contain the ashes of Fakir Bulbul Shah, by whom, tradition asserts, Mahomedanism was introduced into the country. The Mosque of Hazrat Bal is on the Dal, in which a hair of Mahomed’s beard is preserved in crystal.

The Palace is a heterogeneous mass of dilapidated houses, containing that lamentable looking abode, the palace, with its equally hideous Hindu temple. It is of no strength, the outer walls tumble down, and a few shells would cause the masses of pine huts to blaze.

The Fort is a rectangular enclosure 400 by 200 yards, lying on the left bank of the river, below the 1st bridge; at the north end the Kuth-i-Kol canal flows, the south face is separated by a raised causeway and glacis from the suburbs and bazar; on the west the ground is open; on the east is the Jhelum. Hari Parbat, an isolated hill rising out of the water almost like an island, derives its name from Hari or Vishnu, of whom there is a rock-cut sculpture on the side of the slope.

This hill lies between the Dal and Anchar lakes, and rises about 250 feet above the level of the plain: it is of trap formation and quite bare. The hill is surrounded by a stone wall built by Akbar; this is 28 feet high and 13 thick, but is somewhat in ruins, and formerly enclosed the royal city of Nagar Nagar. The wall is strengthened at intervals of fifty yards by bastions 34 feet high, and loop-holed; at present there are but three gateways, over two of them are inscriptions in Persian, to the effect that this Kila of Nag-i-Nagar was built by order of Shah Akbar, the great king, at the expense of one crore and one lakh Rupees (£1,100,000); that 200 masons were employed, and that they and all their assistants were all paid; that it was built in the year of Hejira 1006 (AD 1597); that there never was a king like this king of kings, nor ever will be, and that the superintendent’s name was Koja Mahomed Hussain, a slave of Akbar.

The Fort can be reached by two roads, one on the north side, ride-able, the other on the south side, steep and rugged. The Fort, stone-built, consists of two wings, following the outline of the crest, and also of a separate building below the western wing; the walls are of stone 30 feet high, and 3 feet thick. The south face alone is pierced for musquetry. Barracks for a small garrison are built inside against the walls, on the roof of which the soldiers can stand to fire through the loopholes. The fort armament is antiquated, and the whole affair would probably tumble down if heavy guns were fired from it. The position is a strong one naturally, being protected more or less all round by marshes and lakes.

Water Supply: The inhabitants of Srinagar obtain their potable waters from the nearest canal, or the river. There are a few wells in the city, in gardens, used only for irrigation purposes. The water of the Jhelum is fearfully foul, being charged with the impurities, not only of the city, but also of the towns and villages. Above, it is highly thought of, however, and the people also say that the fish in it are the best for eating.

From the floating latrine system which obtains, some idea may be had of what the water is.

There are but few springs near Srinagar, and they, except the Chashma Shahi, give but a scanty supply: this is on the slope of a hill about one and a half-mile from the city; its waters are very pure and delicious. There is also another spring near it, much smaller, in the village of Thid. A spring called the Drogjun Poker is situated at the southwest foot of the Takht-i-Sulaiman, but is also small. There is a small tank fed by a spring near the AH Masjid; and in the suburbs of Naoshera, to the north of the city, are two springs, the Vetsar Nag and Wantebawan, both of which are appropriated by the Hindus.

European Quarter is situated on the right bank of the Jhelum, between the Takht-i-Sulaiman and the southeast corner of the city. It is a grassy plain one and a half-mile long and half a mile broad, containing numerous gardens and enclosures, and is bisected from southwest to northeast by the Poplar avenue. It is in fact an island, bounded on the south and west by the Jhelum: the Tsont-i-Kol (canal) on the north, and by its Sonawar branch on the east. Along the river at a height of from eight to ten feet above the water behind an embankment, are built several bungalows and three ranges of barracks.

The houses in the Moonshi Bagh are of a superior description, built of stone and wood, and generally of two stories both alike, with a large front room and three smaller back rooms. The Barracks have accommodation for three families in each block.

There is ample camp room behind on turf. The bachelors pitch their tents in three orchard gardens – the Hari Sing Bagh, Goormuk Sing and Tara Sing Baghs. There are three Parsee shops well supplied with stores and wines; a post office and a library.

The Resident’s house, a fine roomy mansion standing in its own grounds of some ten acres, is just above the island, and is a most comfortable abode; next above it is a hospital with quarters for a sick officer, then the library and above that a so-called house for the civil surgeon on duty, most inadequate to the latter’s requirements, for, one or two excepted, it is the worst house in the place. These last-mentioned houses stand close to the river and thus narrow the promenade, which is wide and bordered with willow trees farther up.

A large plot of land has been given by the Kashmir Government for the use of the visitors, and for the purposes of Polo and Cricket. There is also a lawn tennis court near the library, and several rowing boats, including a four oar and a pair oar racing gigs.

The encamping grounds used by visitors are the Chenar Bagh on the Dal Canal, the Island, the Ram Moonshi Bagh, a mile up the river, besides those gardens already noticed.

All these places have this year, 1877, been too overcrowded, and the barracks in the Moonshi Bagh have not added to the celebrity of the place, by collecting hordes of servants within a small compass.

The Cemetery is in the Shaikh Bagh, consecrated by the Bishop of Calcutta in May 1865, where the residence of the chaplain also is, who performs divine service in the upper story of the house.

The Resident resides in Srinagar for six and a half months, removing though to Gulmarg during July and August when the former becomes unhealthy. There is a native agent, a Babu appointed by the Kashmir Government to look after the multitudinous wants of the European visitors.

Srinagar has become quite a fashionable station and much to the detriment of its healthiness.

(This write-up appeared in The Indian Medical Gazette on September 2, 1878)