Walter R Lawrence, one of the most popular British India officers in Kashmir, known commonly as Lawrence Sahab, was an authority on a region pushed to slavery by the East India Company. A land settlement commissioner and author of a celebrated book on Kashmir, his speeches were a grand mix of his knowledge and experience that he acquired during his prolonged deputation to Srinagar

My paper this evening is entitled Kashmir: Its People and its Products… I must, however, say a few words about the scenery and the configuration of the country. The beautiful valley is cradled in the Himalayas at an average height of 6,000 feet above the sea. North, east and west, it is shut off from the outer world by range after range of mighty mountains, while on the south it is separated from the British province of Punjab by rocky barriers 50 to 75 miles in width.

The valley, that is the cultivated part, is 84 miles in length and 20 to 25 miles in breadth, and from the south to north and northwest it is traversed by the great river which we call the Jhelum, the Kashmiris call the Veth, and the ancients called the Hydaspes. The delta of the river in Kashmir is the Wular Lake, a beautiful sheet of water covering some 80 square miles.

On Great Waterway

In its course, through the valley, the river flows gently, and Horace’s words, “lambit Hydaspes,” are the best description of the smooth, easy current of Kashmir’s great waterway. But when the river reaches Baramula it leaves forever the grassy banks of the valley and hurries down its rocky, torrent course to the hot plains of Punjab.

In the valley, wherever you look, you see mountains, ever-varying in shape and colour. There is the grim Haramak, which guards the entrance of the Sind Valley. It was my North Pole, to which we laid our maps when a compass was not handy. There are many legends clustering around Haramak, and the natives say that the presumptuous mountaineer who dared to scale the snow peak would meet with instant death.

In the crest of the mountain, there is said to be a vein of emerald which renders innocuous all snakes which lie within its ken. It is a curious fact that the poisonous snakes of Kashmir only occur in valleys, which are hidden from the eye of Haramak. All around the valley are well-known peaks, all rich in legends, and above all towers the grand promontory of

Nanga Parbat (26,600 feet). The sad fate of Mr Mummery lends a painful interest to Nanga Parbat.

Altitude Superstation

I suppose that all dwellers in a valley who watch great mountains, with their clouds and thunderstorms, are more prone to superstitions and legends than the people who live on the great plains of India; and I attribute much of the superstitious element in the Kashmir character to the daily contemplation of mountain scenery in its most finished form. The colouring of the mountains is exquisite. In the early morning, they are often a delicate, semi-transparent violet, relieved against a saffron sky, and with light vapours clinging around their crests. Then the rising sun deepens shadows and produces sharp outlines and strong passages of purple and indigo in the deep ravines. Later on, it is nearly all blue and lavender, with white snow peaks and ridges under a vertical sun; and as the afternoon wears on, these become richer violet and pale bronze, till the last rays of the sun have gone, leaving the mountains a ruddy crimson, with the snows showing a pale creamy green by contrast. You descend from the mountains, you leave the glaciers fringed with the useful birch tree, and descend to grassy glades surrounded by deep forests of pines and fir.

Down through these forests fall streams white with foam, passing, in their course, through pools of the purest cobalt. Then you come to villages and terraced cultivation, and lastly to the level stretches of the varied coloured rice. Everything in Kashmir is rich in contrasts. The East blends with the West. The delightful plane trees, the magnificent walnuts, the endless willows, the poplars and elms, the wealth of mulberries, and the countless orchards of apples, pears and apricots will remind you of a well-wooded English park.

But the crops, the rice with blooms of art colour, the sulphur petals of the cotton, fringed with the scarlet of the amaranth (our “love lies bleeding”), are of the East. The rounded forms of the trees, the rivers and streams with their banks of green turf and willows recall the West.

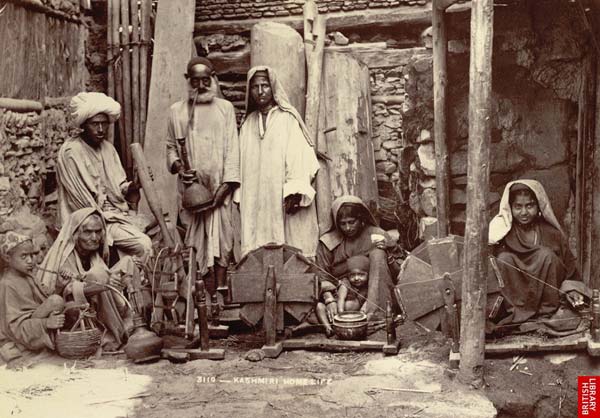

The Village

The very villages are almost English. Like our Saxon ancestors, as described by Tacitus, “suam quisque que dumum spatio circumdat,” and instead of the ineffably dreary and un-village-like look of the Indian hamlet, we have in Kashmir the picturesque homesteads dotted about here and there. All have their little gardens and courtyards. Near the cottage is the wooden granary-not, unlike a huge sentry box. In the courtyards, the women are pounding the rice and maize, and the cotton wheel is for the time laid aside. Dogs are sleeping, and little children are rolling in the sun, while their elder brothers, also children, are away looking after the wild cows and cattle.

Most villages have a delightful brook on which is a quaint looking bathing house, where the villager leisurely performs his ablutions. One of the prettiest objects in the village is the graveyard, shaded by the Celtis Australis and bright with iris – purple, white and yellow – which the people plant over their departed relatives.

Time will not allow me to describe the beautiful lakes or the mountain meadows, known as Margs, where English visitors live in pine-wood chalets on the fringe of the forest. The lawns and flowers, which nature gives would make most gardeners pause. Nor can I tell you of that loveliest angle in the world – the Dal lake, with its beautiful parks Rad gardens, reminiscences of the Moghal times.

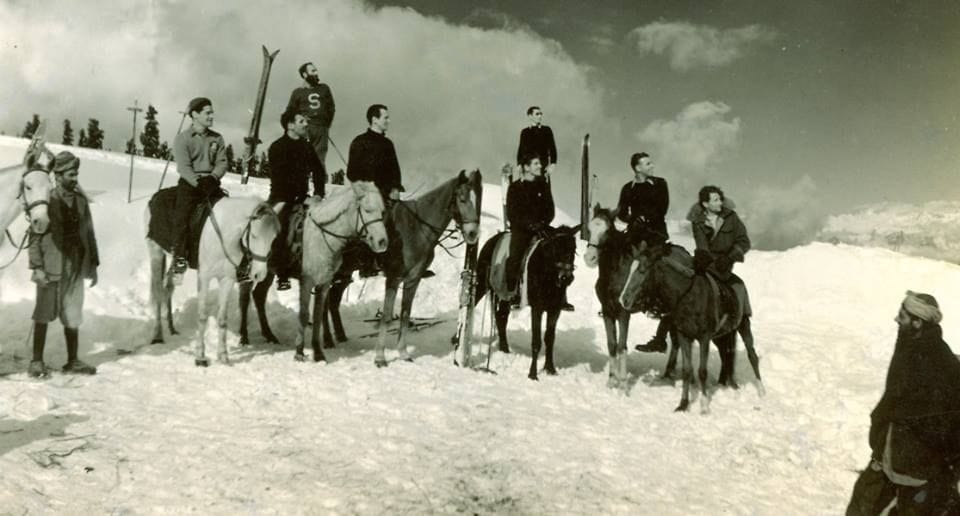

All I can say is, that Kashmir can be reached in three weeks from London; that it has a most delightful and varied climate; and that for a holiday or change there can be no more restful and healthy life than a year or six months sojourn in the valley of Kashmir. The Dolce far niente existence in the houseboats on the river and lakes, or, still better, the gypsy life in the tents wild give a new lease of life to many. You will meet with the kindliest welcome from the ruler of the country and his officials; and if you happen to have a medicine chest with you, you: will be received with acclamation in the most secluded villages. I have often come across English ladies camping by themselves, which speaks well for the courtesy of the people and the safety of the country. Whatever your tastes are, you satisfy them in Kashmir. There is sport, excellent and varied; there is the scenery, ah! such scenery, for the artist and the layman; mountains for the mountaineer; glaciers for the botanist, a vast field for the geologist; and magnificent scenes for the archaeologist; and you can live well in Kashmir on £200 per annum.

Go, if you can, in the early spring, in order to see that marvel of colours, the blooms of the almond groves, and the pink and white promise of the orchards. To enjoy Kashmir, as indeed to enjoy anything in the East, you must enter into the spirit of the hemisphere; you must saunter, and ignore time. If you rush on, from one camping ground to another, you will miss many a point of natural character which might interest and amuse you. And I think the Kashmir people are worth some study.

The Kashmir People

Up to the end of the 14th century, Kashmir was the seat of a Hindoo kingdom strong enough to interfere in the politics of India. The old temples tell more vividly than words that these Hindoos were men of grand ideas. Then, by preaching or persecution, the people left their glorious temples and their picturesque religion for the poor and sullen compromise of Islam.

At the end of the 16th century, a further change awaited the Kashmiris. The beauty or rumoured wealth of the valley attracted the adventurous Moghals, and after obstinate fighting in the difficult passes, Kashmir came under a foreign yoke. These grand Moghals loved the valley; they built “sunny pleasure domes,” such as Coleridge dreamed of in ‘Khubla Khan,” and they planted the noble plane tree. They have bequeathed to posterity the love stories of Selim and Naurmahal.

On the whole, the lot of Kashmir was not unhappy in the Moghal times, and the people still speak with affection and admiration of Emperor Jehangir and his lovely consort, the “Light of the World.” But to the Moghals the brutal and oppressive Pathans succeeded. Give a Pathan a chance, and he is a bully and a friend. He had his chance in Kashmir and he ruined the country and the people. The Pathan was driven out by the Sikhs. It was a change for the better, but the Sikhs left much to be desired.

Moorcroft, who travelled in Kashmir in the Sikh times, tells us that the punishment for the murder of a Kashmiri by a Sikh was a fine of two rupees. Crossing a pass, he came upon a young man whose throat had just been cut and saw three other corpses, “some of the followers of a native official who, to the number of forty-five, had perished in crossing the path lately in rough and cold weather against which they were ill defended by clothing or shelter. Some of the people accompanying us were seized by our Sikhs as unpaid porters and were not only driven along the road by a cord tying them together by the arms but their legs were bound by ropes at night to prevent their escape.”

Kashmir Sold

In 1846-just fifty years ago – we made over Kashmir to Maharaja Gulab Singh, chief of the warlike Dogras, a Hindoo. He was a stern, strong ruler; feared and respected by the Kashmiris. His methods were Oriental and effective. Kashmir was full of bandits, and Gulab Singh made up his mind to stamp out crime. He made each punishment an object lesson.

I have heard from eyewitnesses many of Gulab Singh’s endeavours to make punishment a deterrent. A soldier had murdered a child for the sake of her jewellery – a common form of crime even now in India. Gulab

Singh sentenced him to hard labour on the road.

Months after, Gulab Singh happened to be walking along the road on which the criminal soldier was working. He asked him how he was progressing, and the man, encouraged by the affable manner of the

Maharaja, said, “Don’t you think I have been punished enough for my little offence?”

“I quite forget what it was,” said the Maharaja. On hearing what the offence was, the Maharaja mused and then called to a carpenter who was working on a bridge. He then demanded a pen and ink, and removing the criminal’s clothes, he carefully marked his body into four parts.

“Now,” said he to the carpenter, “saw him in four pieces, and send a piece to each of the districts. I will show the people that I do not consider child murder a little offence.”

These punishments have had their effect; crime is non-existent in Kashmir. Within the last ten years, only one Kashmiri has suffered capital punishment. The people are afraid to commit crimes.

Bad Name

You will see that Kashmir has undergone many changes in its governors, and there is deep-rooted disbelief in the continuity of affairs. The governors and their deputies have, unfortunately; felt no sympathy for the people so that the Kashmiris are hopeless of benevolence or justice in their rulers. It has been the deliberate policy of the Brahman officials of Kashmir – known as the Pandits – to exaggerate the difficulties of administration in the valley. They excused their own corruption, cruelty, and ignorance by assuring their masters that the Kashmiris were lying, lazy, and dishonest. No dog has ever been given so bad as the Kashmiri serf, and I was solemnly assured when I began work in the valley, that fair and humane methods would lead to a revolution and to the depletion of the treasury.

Apart from the evil effect which cruel and unsympathetic governors have worked on the timid character of the Kashmiri, other causes have conspired to make him doubtful and hopeless. Kashmir is a country where nature rejoices in her strength. Earthquakes, floods, fires, cholera, and famine are familiar to every generation.

Take one village as an example. In the village of Pattan there is a normal population of 165 families. In 1885, seventy persons perished in the earthquake. In 1892, fifty-five persons were carried off by cholera. This is enough to unsettle strong-minded Anglo-Saxons, and with the tyranny of man on the one hand, and the terrible vagaries of nature on the other, the Kashmiri has become incredulous of the existence of good in man or in nature. He always gives me the impression that he has just recovered from a fright, or that he is expecting some disaster.

They have sad memories; their very songs are those that look back to a melancholy past and forward to a melancholy future. Hardly a day passes without mention of the great famine of 1877-79, when men turned cannibals, and three-fifths of the population is said to have perished. The Kashmiris sigh as they quote the proverb Drag tsalih, tah dag tsalih na. The famine has gone, but its stains remain.

And though famine has gone, I hope and believe never to return, and though tyranny, torture, and the corvee have gone, their stains remain, and we must make allowances for faults in the Kashmiri character.

They are timid and somewhat effeminate. They wear a womanly dress – a kind of heavy woollen nightgown falling to the feet. Under this, if it be cold or wet, they insert a small earthen brazier of hot embers, known as the kangar, which keeps them warm, but it has its drawbacks. They go to bed with their kangar, and set the house on fire, and it is said that the brazier is the fruitful source of cancer.

They are lazy when they have no interest in their work, but when they are working for themselves they are most energetic and efficient. Up to quite recent times, no one ever knew that he was certain of reaping the fruits of his labours. Their simple proposition, Yus karih gonglu sui karih karo, he who plows shall reap, was ignored at harvest time, and everybody took what he liked. Everything was taxed, and the farm of a tax often brought with it social distinction and sometimes wealth. It was part of my business to put down the soldiers of fortune roving, often without a commission, to collect taxes on violets, birch bark, or some medicinal herb. I explained to them that there was not room for them and for me, and that violets must bow to the land revenue.

Grave Charges

With officials plundering, and hordes of tax farmers, real and fictitious, with regiments of soldiers whose sole duty it was to assist in the collection, it is no wonder that the Kashmiri took refuge in lying and subterfuge. When face to face with the Pandit officials the Kashmiri villager will urge his case with the fervour of St. Paul and the inaccuracy of Ananias: but remove the officials, and set him up before his fellow villagers, and the Kashmiri will speak the truth.

It is a grave charge to bring against a nation to say that it is a nation of liars, and after six years’ constant intercourse with the people of the villages, I can say that the charge is not true. All cases connected with the land came under my jurisdiction, and it was my practice to hear these cases on the spot.

Kashmiri was ashamed to lie in the presence of his neighbours. If he did sometimes lie, there was a telegraphy in the eyes of the men who stood around which gave a quick clew to the truth. The parish council of white-bearded elders was to me a most useful institution. I do not say that the Kashmiris are an exemplary people but I do say that they have many excellent qualities; and I maintain that under a just and sympathetic government, they might grow into a fine, manly nation. They are intellectual, dexterous, and witty. They can turn their hands to anything.

Like Ireland

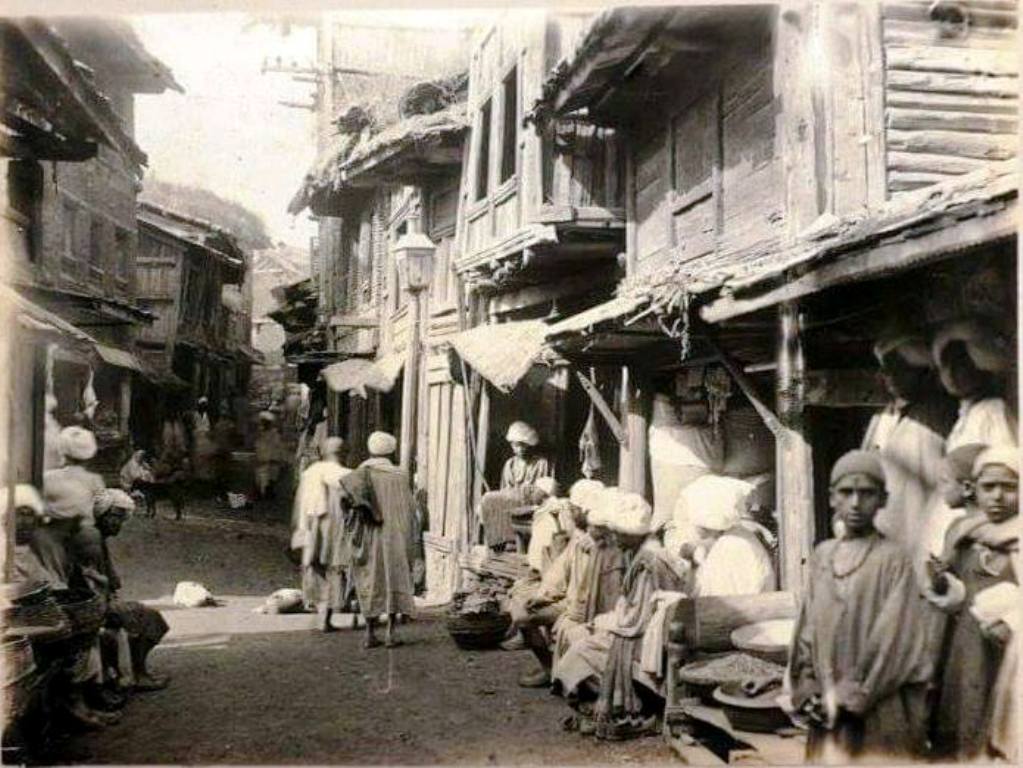

There is cultivation in Kashmir that would astonish Europeans: there are art wares in Srinagar that have astonished the world. The meanest peasant likes to display his wit, and every day I heard some shrewd, humorous remarks.

In their domestic life, they are admirable. One never hears of scandals. Like the Irish they are kind to their children and the old folk. There are many points of resemblance between Kashmir and Ireland. Both are small countries, which have suffered or derived benefit from the rule and protection of more powerful nations, yet have never welcomed any change or improvement.

Both Kashmiris and Irish love a joke, are fond of harmless deceit and are masters of good-humoured blarney. Both have the same deep-rooted objection to paying their rents.

The Kashmiris are a very gentle people. They quarrel but never go beyond invective or abuse. That sight of blood is dreadful to them, and in some villages, if a fowl has to be killed for food the execution devolves on the village priest. But in invective, they are past masters. You will hear two women quarrelling from their respective boats. The men sit quietly enjoying the scene of the noise. For hours the shrill abuse continues, and when evening comes and the women are hoarse they rise and invert their rice baskets. This is the sign that the fight is over for the day, but in the early morning the baskets are set up again and the wordy war begins afresh.

Peculiar Protests

People talk of Billingsgate, but commend me to a Kashmiri virago. Kashmiri is loud and voluble when he thinks that he has been injured by a man. A common expression is that he will make himself heard as far as London. Sometimes when I had the misfortune to give a decision regarding land against a man, who there and then lifted up his voice and said he would proclaim the injustice of my order as far as London, I have taken him aside to ask where London was.

The inevitable answer was “London, as your honour knows well, lies beyond Sukkur Bukkur on the Indus.” This was the ultima thule of Kashmiri peasants’ thought.

They are a people of hyperbole and symbols. Formerly, it was no doubt necessary to attract the attention of their rulers by some striking demonstration. Men who have a grievance will fling off their clothes and smear themselves with mud. The nakedness implies destitution; the mud signifies that they are reduced to the condition of a clod. Many a time I have seen a procession: one man wears a shirt of matting, another has a straw rope around his neck, with a brick pendant; another carries a pan of hot embers on his head, while in the rear comes a woman bearing a number of broken earthen pots.

This was bad, but more inconvenient was the practice of casting a plow under my horse’s feet as I rode along, in order to emphasize the fact that agriculture no longer possessed charms for the proprietor of the plow.

Once, as I was hearing petitions, I noticed an elderly Hindoo standing for at least five minutes on his head. No one took any notice of him. At last, fearing the old man might injure himself, I had him placed on his feet. When questioned as to his attitude, he said that, thanks to my arrangements, his affairs were so confused that he did not know whether he was standing on his head or his heels.

A man once came to me carrying the corpse of a child, and alleged that his enemies would not allow him even burying ground. He had a land suit in his village, and he wished to strengthen his case by arousing my indignation.

Once a man appeared at Nagmarg, a place some 9,000 feet high; he was stark naked, and said that his uncle had turned him empty into the world. It was bitterly cold and night had fallen, so I gave him a suit of old clothes, and, by way of jest, said that, as he was now dressed as an Englishman, he should assert his right. He shambled down the mountains, and the next day the uncle came into my camp, charging the nephew with an aggravated assault, and offering in his shattered appearance convincing proof. It is always dangerous to jest with Kashmiris.

Muslim Subjects, Hindu Ruler

The ruler of Kashmir is a Hindoo. Over 93 per cent of his subjects are Mussulmans. The officials of the country for the most part belong to the rigid Brahman caste. But the oppression in Kashmir, which up to quite recent times formed the text of newspaper articles and books of travel, was entirely official and did not arise from religious intolerance.

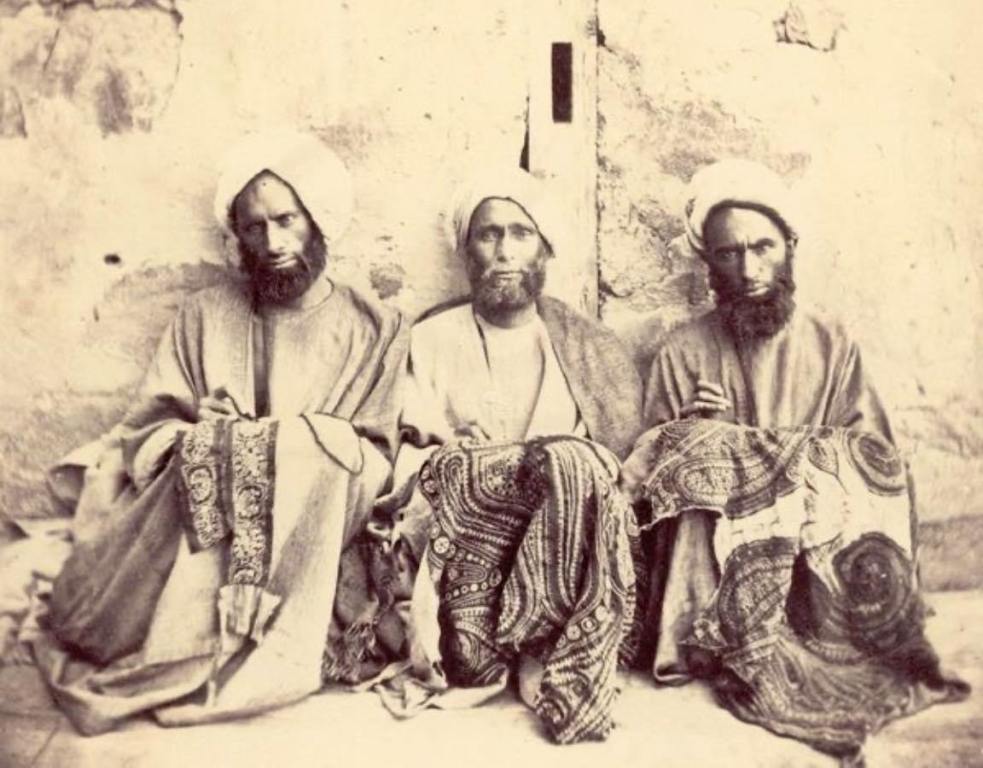

There has of late arisen in India a spirit of revivalism in the two great religions of Brahminism and Islam. In Kashmir, however, Mussulmans and Hindoos live together in delightful amity. One reason of this charming tolerance is the fact that beef is never heard of, and kine killing is an offense punished most severely. But the chief reason is that the people of the valley, Mussulmans in name, are at heart Hindoos. The religion of Islam is too abstract to satisfy their superstitious cravings, and they turn from the mean priest and the mean mosque to the pretty shrines of carved wood and roof bright with the iris flowers, where the saints of past time lie buried.

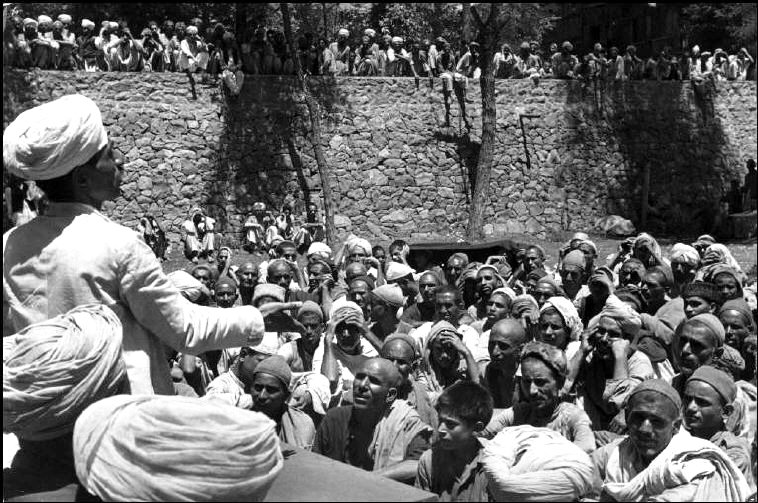

Pir Parast

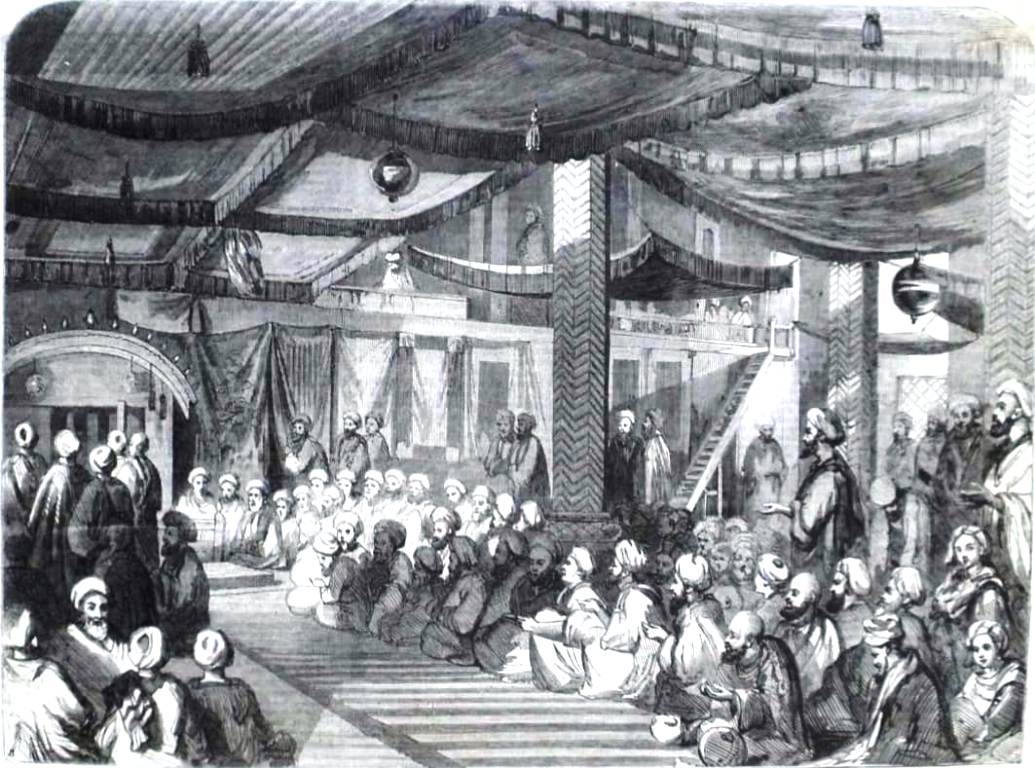

The Kashmiris are nicknamed in the East the Pir Parast, or saint worshipers. They believe that “the saints will aid if men will call,” and regard a dead saint as more efficacious than a living priest. All that there is of adoration and reverence in the Kashmiri character expends itself on shrine worship, and the poor priest and the ruinous mosque are neglected until cholera or some great calamity comes.

Then Islam raises its dead: and in cholera time, I have heard the priest addressing the silent, frightened crowd as they sat helpless in the graveyard. He used King Solomon’s very words at the dedication of the temple – “If there be in the land famine, if there be pestilence. Then hear thou in heaven thy dwelling place, and forgive.”

The voluble Kashmiri is silent when he knows that his troubles are not of human origin. I was in Srinagar, in 1892, when the daily death rate from cholera had risen to five hundred. I was struck by the hushed silence which had fallen on the famous City of the Sun.

A native friend explained it. A Panditani had lost a son, and mourned loudly. A spirit appeared and taunted her with wailing for one son, adding that before the night she should have real reason to mourn. Before night she had lost her husband and her two other sons. No one wailed after this.

Kashmir is rich in superstitions, and lovers of the supernatural will find a grand field in the villages of the remoter valleys. Night after night as I sat by the campfire I would hear the quaintest and most stirring legends.

Demons on the mountain passes in the shape of fair women, dragons in the deep green lakes, which are found on the higher ranges-underground rivers and an underground world where the serpent gods hold sway, divining springs and trees of ordeal-and caverns where men controllers of the wind live their solitary responsible lives. The Brahman astrologers of Kashmir are famous in the East, and the wild soothsayers of the valley have an immense reputation. It was curious to have daily business with clever, shrewd farmers and officials, all absolutely believing in these old-world superstitions. But the things dreamed of in the Kashmir philosophy date back to the times of the old saints, and the Kashmir mind, keen and intellectual in mundane affairs, is in things spiritual slumbering in the beautiful old shrines.

Key Products

I must now leave the people and say something of the products of the valleys. Agriculture was my chief preoccupation, but it would not interest you to hear about our staple crop, the rice. It will be more interesting to know that almost all the vegetable products that exist in a temperate climate can be grown in the Vale of Kashmir. It is my hope and ambition that Kashmir may become the California of India.

Our fruit is magnificent, and it comes to us so easily. We have everywhere an endless supply of wild stock, and from our nurseries, we give out thousands and thousands of trees grafted or budded with the best English and French varieties of apples and pears. A tinning industry was introduced two years ago, and is thriving. We have large vineyards, from which excellent wine – Medoc and Barsac – is made. We have recently replanted these vineyards with American stock in order to combat the phylloxera, which has penetrated even to remote Kashmir. We have made excellent cider, and the brandy which we distil from the wild apples and pears is pure and potent and is the one spirit drunk by the natives of the city. We have succeeded admirably with hops, and the financial results would surprise Kentish growers.

Silken Hopes

But our great hope lies in sericulture. Silk is an ancient industry in Kashmir, and it is probable that the valley was a producer of the old Bactrian silk which found its way to Damascus and other centres of manufacture. But evil days befell silk, and in 1878, disease obliterated the industry. In 1889, when I first went to Kashmir, it was decided, on the advice of Sir Edward Buck, CSI, to rehabilitate sericulture, and to stamp out disease by following the Pasteur system of microscopical examination.

For the first two years, it was difficult and disappointing. A native with a microscope is a most uncertain combination. But eventually, we succeeded, and a few weeks ago the first Kashmir silk found a sale in London. As regards its quality, experts can speak. I can only say that being an amateur, I have advised the state not to incur expense on improved reeling appliances, and my object has been to make sericulture pay its expenses, and to demonstrate that good silk could be raised in Kashmir.

I can give you no good idea of the wealth of mulberry trees that are wasting and waiting for the silkworm. I can only say that European capitalists will find in Kashmir the elements which contribute to successful sericulture. The Kashmiri house is eminently adapted for the rearing of silkworms; there is an abundance of skilled labour in the presence of the Kirm kash, or worm destroyers, families with a hereditary connection with silk; and, above all, there is an endless supply of mulberry leaf.

An Indian California

All that is wanted to realise my dream of an Indian California n European capital and European skill and energy. Already Europeans are carrying on a profitable business of carpets, and their capital and supervision have proved of great assistance to the unfortunate weavers of the old shawls for which Kashmir was once famous throughout the world. The French and German war destroyed the shawl trade, and the poor weavers, too soft and too sedentary for agriculture, would have perished had it not been for the carpet trade.

Everywhere we have splendid water power, and if capital were forthcoming, cotton mills might be erected which could supply Kashmir and Central Asia with the cloth. Our local cotton is excellent in quality, and the cloth of the handlooms is preferred to the piece goods from India. It wears longer and is better value for the money. Then the valley abounds

in fibres. One of these is especially worthy of European notice; we call it Yechkar. This is the Abutilon Avicenna, and its fibre has been pronounced superior to Indian jute and finer than Manila hemp.

Born Artisans

The people of Srinagar are born artisans, and the European capitalist will find apt men, of all handicrafts, ready to hand. Just as the Kashmiris prefer the home cotton cloth, made locally, from the native cotton, so they prefer the iron of Kashmir to the imported metal. It was described to me by an expert, who held most sanguine views as to the future of Kashmir iron, as being equal to mild steel. Many hold that the valley and the mountains which surround it are rich in minerals, and the chance discovery of the rich sapphire mine in 1882 suggests that organized exploration might result in further discoveries.

As I have pointed out in my book on Kashmir, it is a mistake to suppose that the natives of the valley would be eager to disclose the existence of rich lodes. They are agricultural or pastoral people, and their experience in the past teaches them that the discovery of mineral wealth is attended with drawbacks, in the shape of forced labour and of numerous officials who must be fed. I have often discussed the question of iron mining with the villagers who live near Sof, the chief iron field, and if their views on the subject of mineral wealth represent the general ideas of the people, it is no exaggeration to say that the Kashmiris detest the very name of mining.

Time will not allow me to tell you of the floating gardens of Kashmir, like the Chinampas of old Mexico; nor can I tell you of the saffron fields, for which the valley is renowned. The author of the Ragatarangini, the famous Sanskrit history of Kashmir, who began to write in 1148 AD, alludes to the saffron in his introduction:

“Kashmir is a country where the sun shines mildly, being the place created by Kashaypa as if for his glory. High schoolhouses, the saffron, iced water and grapes, which are rare even in season, are common here. Kailasa is the best place in the three worlds; Himalaya the best part of Kailasa, and Kashmir the best place in Himalaya.”

I agree with the old chronicler, and I think that any of you who can find the time to visit Kashmir will also agree that it is the best place in the world.

(The speech was reproduced by Scientific American in its Supplement, No 1097 on January 9, 1897.)