Srinagar’s water bodies have historically remained a self-sustaining eco-system in which people lived, worked and thrived throughout. Life remained unchanged for a long time as this 1954 travelogue by Pearce Gervis explains

= Going down the river we turned off into the canal, which joins it opposite the Sher Garhi White palace. This canal, the Tsunt-i-Kul or Apple Tree Canal, is ugly and congested with barges for some considerable distance up. After a few hundred yards the flow of its waters into the Jhelum River is controlled by great iron gates, and at times when the gates are first lifted, it takes hours for the flood to slow down sufficiently to permit anything like safe travel through it in a flat-bottomed shikara.

The canal twists and turns. More especially during the spring and the autumn, there are always dozens of great houseboats endeavouring to go either up to the Dal Lake, or down to the river, and it needs all one’s patience to stand the strain of pushing between these and the barges lining the banks, wondering the whole time when the frail shikara will be crushed to matchwood.

Boat Makers

Just when we imagined we were clear of these, we came on great rafts of logs filling the waterway outside the boatbuilders’ yards; these were those we had watched being carried down by the river coming from miles up-stream, the ferryman controlling them sometimes living in a barge which trails behind, or in the temporary shelter erected on them, and steering rafts which are sometimes a hundred yards long. How they managed to get them through the gate and up the canal was beyond me.

In the tree-shaded yards, we could see the boat builders at work; the wood is sawn and worked to shape and size only when actually required for any part of the boat. The great logs were resting over a cross-bar, it being much like a see-saw with one end on the ground. At each end of a great saw the men stood, one on the ground under the log and the other on the bar on which it rested, and so, up and down they cut planks from the log, gradually getting lower and lower so that finally the man below was on his knees sawing.

Pearce Gervis has been an interesting British resident. He first studied law, then studied ground aeronautics at Oxford and joined the Royal Air Force. Then, he enrolled himself as a student in the London Hospital Medical College. He abandoned everything and started breeding poultry and wrote a guidebook to poultry breeding. In 1938, he returned to the Royal Air Force and served in Europe, West Africa and Asia. It was his posting in undivided India that he wrote the book on Kashmir.

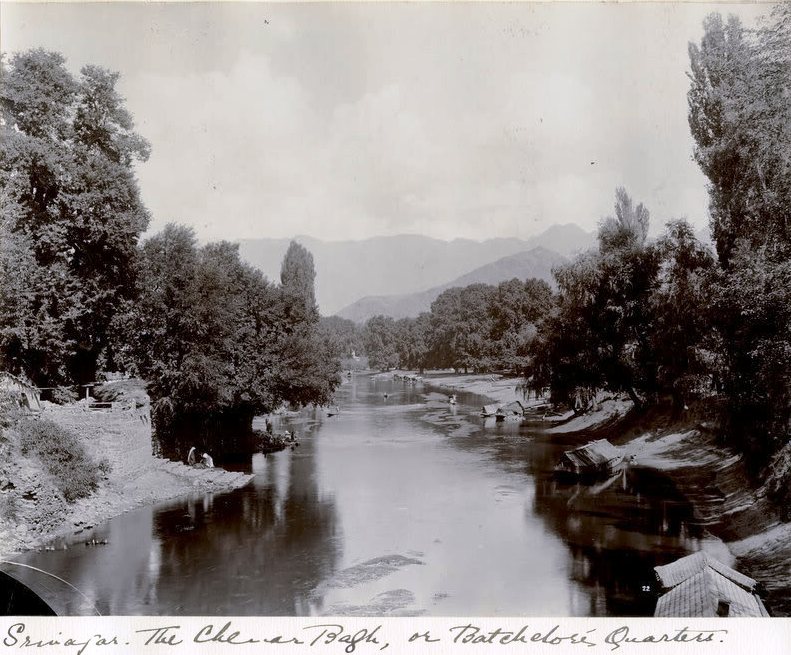

Bachelors Island

About a mile up from the Jhelum, just on a bend, we came upon a Hindu temple with a shining silver-pointed dome, built high on the bank among shady trees. The priest’s house on the waterfront was quaint with carved windows and stone steps under an arch room going down to the water, where a servant was doing some washing. From then on, the right bank is known as Chinar Bagh, being a mass of giant elephant-grey tree trunks and branches with great maple-like leaves, fresh green in the spring, flaming red in the autumn, gradually changing to a glorious bronze and holding to the trees for weeks before falling to the ground to be gathered up and stored away for winter fodder for the cows, which even at that time of the year as they grazed seemed to prefer the odd fallen leaf to the emerald green grass.

Save for the fact that it is flooded over during the spring and early summer months, the tree-covered island with its green turf would seem to be an excellent place for a houseboat. At one time it was most popular and called Bachelors Island, for from here the city and the European part of Srinagar is close and handy, whilst the Dal Lake is quite near.

The Village

Under the village, which is protected by a great bund, the canal turns sharply to the right and we soon arrived at the Dal Gate lock. We were fortunate for once, for they were letting the water out of the lock into the canal, the lake being on a higher level. No sooner had just a chink shown between these great wooden gates than the first shikara pushed its way out, closely followed by another, then others, some with passengers, others almost overloaded with vegetables, all fresh and clean and colourful, great watermelons, purple brinjals, baskets of scarlet chillies, cauliflower and tomatoes. The boatman on the journey into the city, worked hard, usually sitting on his haunches in the front of the flat bottomed punt and scooping his way through the other shikaras, with a small boy at the back adding his contribution. On the journey back to the market gardens later in the day the man will probably be sleeping in the bottom of the boat, whilst the boy will be paddling.

The lock keeper is a lover of flowers and the banks are a mass of colourful beds, which we could only see when the water was raised to the lake level before the gates at the other end were opened up. In the meantime our companions in the lock, box wallahs selling carved boxes and embroidery, who had pestered us to “Only look see, sahib!” having given us up as hopeless, moved towards the exit gate, to press through as soon as they moved, and a shikara which until that time had remained at the back end, quietly came up beside us, the gentleman passenger, wearing a red fez, bent forward with a toothy smile of greeting and asked, “I wonder if either of you gentlemen would like to visit my museum which is just over there, to inspect some of the valuable Persian carpets I have on display?”

I can only conclude that he spends his day in the lock, soliciting trade in this fashion, and from his hired taxi shikara, smart suit and well-kept shop, it would appear that he is successful with this new fashion of approach to visitors who cannot get away from him until the gates open. But I must admit that although they press, these super Kashmir salesmen do not pester beyond one’s patience; they instinctively know when hopes of a sale have gone, and move on with a friendly grin—doubtless hoping for a change of mind, for “There is always tomorrow”.

Swarming Shikaras

Outside we pushed our way through the swarm of waiting shikaras and punts, and on towards the lake. The journey had so far taken us nearly an hour and a half in going round, for that reason most of the people who live on the river send their shikaras loaded with lunch baskets off before breakfast, and follow by going through from the Srinagar Club to the Dal Gate on foot, for it is only a quarter of an hour’s most pleasant walk under the shady trees which are planted on either side of the shallow canal they follow.

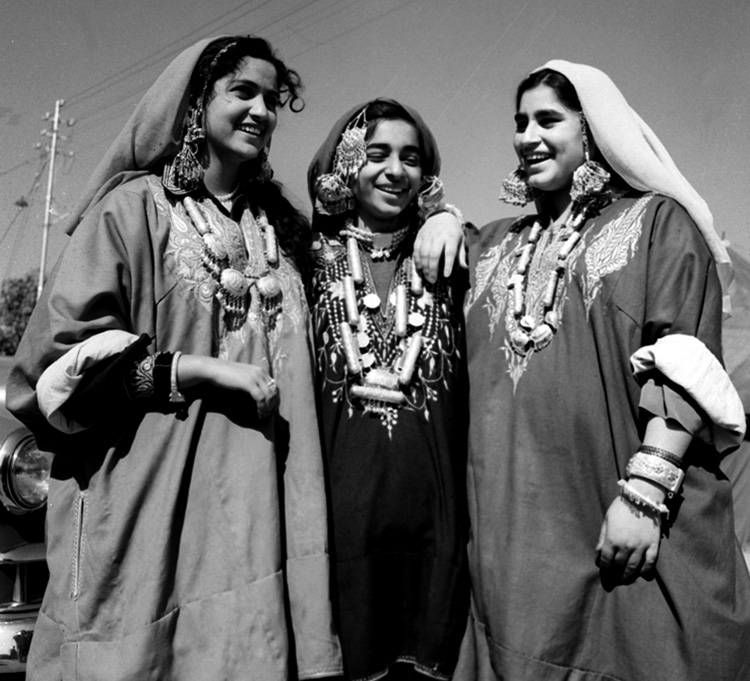

On this first water journey, we turned off by a wide stretch of water on the left and followed it to branch off again into narrower channels. On all sides were plantations of willows, with houseboats, moored, their verandas looking over the canal, and nearby the ever-present cook boat with seemingly dozens of children playing nearby and women on the banks pounding corn with great poles in stone mortars, usually working in pairs and singing as they worked; we watched a mother and her daughter both pounding in the same mortar having a terrific row, both venting their temper with each thrust—the corn made into flour no doubt in record time. They seemed to be covered with silver ornaments, many bracelets on the arms, and dozens of earrings hanging, which with the older women were actually passed through the lobes which had been dragged down in a most ugly fashion; with the younger ones these had been supported by a wire which passed over the crown of the head, but this I did not know for some time, the women are seldom seen with heads uncovered.

Irrigating Vegetation

On either bank, the earth had been built up with silt or weeds from the water; it was black and looked good. Here and there a pair of twin poles was set upright on the bank, sometimes a growing tree was used: on top of this a pole was balanced, one end held the weights, great stones, the other had a bucket-shaped like the traditional witch’s cauldron suspended from it by a long rope.

A man wearing only a dirty cloth skull cap and baggy pyjama-like grey cotton trousers—with no shirt or shoes —stood on the bank edge holding the rope, dragging it down to dip the bucket in the water; the weight did the heavy work of lifting it from the canal, and all that he had to do was to tilt it with his foot into a gully which led away through his garden. He worked as though mechanically; seemingly untried he did not even welcome my asking him to stop for a minute so that I could take a photograph. These Kashmiri men are certainly tough and strong, more especially when working for themselves. Their physique so seen is magnificent, their colour a glorious bronze.

Around Looms

We continued on until the canal divided, on the right side we could hear and then see through the casement windows of a factory, the looms on which mats were being made, the verandas were festooned with hanks of dyed wools. In the centre of the V was a garden, garlanded with climbing roses and the rest a splash of many colours. The house was not unlike the Residency in its design; it was that of the Governor.

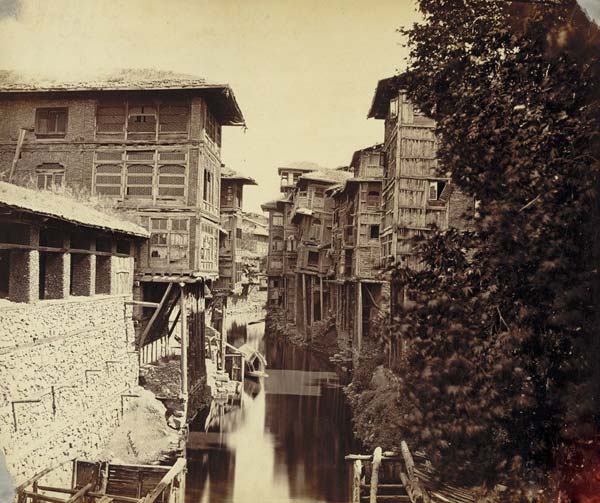

Following up the canal I realized that although we had for the past hour been right away from the city, we had now returned by a back way to it, for when I looked up at the buildings which were getting close upon us as the canal narrowed, I occasionally caught sight of alleys so common in Srinagar. We passed under a very old stone camel-shaped bridge, which reminded me of willow pattern china; ahead some of the verandas, which overhung the canal were supported on long poles which were set on its banks. The water was getting shallow; it was filthy and stank, whilst its flow was blocked at places by truckloads of garbage, which had been thrown there.

The Mar Canal

The Mar canal, the spring beauty of which I had read and heard so much, had become nothing more than a rubbish dump, so that we were glad to scramble ashore, climb up the steep flight of stone steps and walk back on a road to meet the boatmen who had somehow managed to get the shikara stern first into deep water. In it, we made a hurried return to cleaner water and fresher air.

As we came into more open country the canal gradually spread its banks, the main waterway down which we had come turned off to the right; to the left, we came out on a wider part close-covered in water-weed, emerald green in colour and as bright, soft and flat as a velvet billiard table. Looking ahead we saw that the canal continued, gradually becoming less wide, shaded by overhanging silver-grey willows on the banks. It seemed as if there could be no way through, but as the shikara moved forward the men kept to the middle of the stream and the weeds opened up for our passage as the nose of the boat touched them, closing again after us, but making hard work for the paddlers as they dipped into the masses of weed which below the surface were matted and long like tangled hair so that it had to be flung off after each dip as it clung to the heart-shaped paddle.

It was interesting to watch the little flock of fat geese and ducks which every house, whether large or small, seemed to own.

There were always dozens of children playing in the water, usually naked and always laughing and shrieking, the sound of their voices only broken by the occasional shrill shout of one of the mothers – Kashmiri peasant women’s voices are not pretty when they are excited or shout.

Turban Fright

It was amusing to one who knew his north-west India to see the bigger boys, on seeing the pugaree of my Pathan bearer, yelling to each other, dash out from the water and race as though for their lives; such is the Pathan’s reputation after hundreds of years of raiding Kashmir when among the loot, they carried away as many good-looking boys as they did beautiful Kashmiri girls.

Nearby women were making rush mats on the bankside. Two trees had been selected some twelve feet apart, and suspended between these at about two feet above the ground was a framework, the ends being wooden poles, much like broomsticks. Between them, harp-like strings were run some six or eight inches apart. Through these strings the women were threading the rushes – hand weaving – and after two or three had been so worked between the strings, a loose wooden bar – itself on the strings -was pushed down onto the rushes to make them sit close. Nearby stood bundles of rushes which had been collected up from the ground after being dried off, and as we watched a boat came alongside the bank stacked high with more which had just been cut, these being easily ten feet long.

College Boat

We passed close to other passenger shikaras, both crews of boatmen endeavouring to hold the narrow cleared channel. There was a college boat, the master sitting on a kitchen chair in the middle of it and the boys, many of whom had given up oars for paddles, rowing and scooping among the weeds, hopelessly out of time and moving forward at a slower pace with their twenty-four than we did with our three. Then there were the flat-bottomed grey little punts, each with an old woman squatting on her haunches at the front, grey hair hanging round a weather-worn face and grey eyes now dull, throwing back the wide sleeves of her frock-like gown and scooping away through the weeds, for she would cling to the side of the canal in the same way as the younger women who continued scooping the water though feeding a baby which they somehow contrived to rest across their knees.

The men who passed us with punts would be standing up and bending as they went their way, pushing with long thrusts of the pole instead of a paddle through the dense waterweed, their magnificent muscles standing out. many unusually handsome in countenance, so that one wondered, if brain matched brawn, why they continued to labour as they did with small patches of land, or in meagre jobs, for all wore the stitched cloth skull cap of the peasant class, the more intelligent ones affecting an individuality by placing them at jaunty angles, the less bright ones planting them glumly and squarely on their heads. Here and there, usually at places where the waters branched off, small shops would be found, either built on a little patch of ground or on piles driven in close to the bank so that boats and shikaras could come up alongside. Most of them sold groceries and foodstuffs, but there were some with sewing machines whirling, even potters’ shops where the crude but serviceable Kashmir “china” is made, this being glazed earthenware coloured yellow, green, red or brown, with thumb mark patterns and quite serviceable for everyday use, besides being extremely cheap and decorative though brittle. There was one shop, the owner of which also plied the waterways and lakes in his shikara, where miniature wooden houseboats, cook boats and shikaras were made and sold, these being souvenirs the visitors’ love, especially if they happen to be models of the houseboat on which they are living, and the majority are standard to type.

There were well-built houses with gardens, one or two of these laid out in the English fashion, much as one would find on the banks of the River Thames, others after the Kashmir style, with a little garden, a many-storied house of red brick, flattish roof and open windows, near to the water.

Basket Makers

At one place we saw a shikara being loaded skyscraper high with willow baskets of all kinds, lunch baskets, work baskets, bottle baskets, market baskets and shopping baskets of many shapes and sizes, with sets of these fitting one into the other. These were being carried out from a so-called “factory”, a shed in which, we found when we got out to have a look at it, a complete family of basket makers were working. The head of the family, a very old man, was blind; his grandson was telling us that he also expected to become a grandfather at any time. They proudly explained that it was English Willow that they used, meaning that it came from willows, which had been imported from England long before. As I watched the family working on the cane, although by then not moving so quickly with his fingers, the old man finished his baskets well before the others who stopped to look up to make a point as they spoke to us.

The canes are hacked from the trees in the late summer, tied in bundles and placed in a high V of the branches so that the cattle and goats cannot get at them. In the winter the leaves are stripped as fodder for the cattle and the canes of suitable sizes graded and used for basket making, after being steeped in water. The work coming out from this garden factory was excellent. I checked up on prices in the city and found that the middleman made a profit of nearly two hundred per cent on that which he paid the makers. I suppose it had never dawned on those people to look into this themselves and consider the advantage of opening a shop.

(The first of the two-part series on the people living in water bodies, these passages were excerpted from the book This Is Kashmir by Pearce Gervis that Cassell & Co published in 1954)