In one year, it took Tahir Bhat eight visits to police station Vilgam to attempt getting even the basic information about a watershed event. Finally, he traced witnesses and survivors to understand why the residents in Pazipora still tremble and fret with the memories of August 10, shooting, that killed 26 civilians in a few minutes, 28 years back in 1990

On August 10, 1990, the dusky Pazipora hamlet located within serene paddy fields, almost 30-minutes drive from Kupwara in north Kashmir woke up to the Fajr prayers. Soon after it was beginning of the routine; working in the paddy fields and the vegetable gardens. Children dressed up in their uniforms left for the school. Those working in government and private sector – though quite a few, also left. The village women followed the routine – the younger went to the fields and the seniors got busy in preparing the lunch.

This belt also maintained the traditions of women taking lunch in wicker baskets to feed men and women working in the fields. The life in the belt was normal until an army convoy came into the village at 11 am. Within no time the situation shifted and no lunches were served anywhere.

All of a sudden army convoy came to a halt and army men got down and spread around. Within no time their guns roared. They fired upon whosoever they spotted. There were cries and shrieks across the village. In no time, bodies of 26 civilians lay scattered across the village, mostly in the fields.

There has not been a visible follow-up of the case but the massacre is part of the folklore. Memories of the massacre are still fresh in the minds of the eyewitnesses and survivors. They still tremble in fear as scenes from that day refuse to fade away. Apart from killing 26 people, army men allegedly raped three women, injured sixty people, and burned down ten houses.

“It was the time when people were busy in harvesting grass in their paddy fields,” said Ghulam Nabi Tantray, a salesman at Fertiliser Cooperative, now the village Sarpanch. “As the grass was high, those harvesting it in the fields were invisible. But when the army fired the first few shots, they got up to see what has happened. That is when the army started shooting them like ducks.”

During the early 1990s, both police and civil administration had little or no control over the affairs of the state, a police official from that area admitted. So, it was locals who risked their lives to ferry injured to the hospital.

Tantray, the Sarpanch, was not only a witness but a victim too. “I was home when I heard army has cordoned off our village,” recalls Tantray. “Given the fear that the crackdown (now called CASO) would trigger, most of the residents started running towards neighbouring villages.”

Watching residents flee, Tantray’s wife begged him to intervene. “I first refused but when she pleaded again, I gathered all my courage and moved towards the fields,” Nabi said. “But there was no room for any intervention. The forces were firing at every head that would crop up from the green fields. Even I received two bullets in my thighs.”

What happened later was cruel. “Bleeding, I was dragged out from paddy fields and put in an Army truck. I could see other injured persons lying in the same truck, crying in pain and screaming for help,” Tantray recalls. “Some seriously injured were succumbing to their injuries and I could hear them recite the Kalima.”

Tantray hoped that the truck would drive them to the hospital. But they were taken to army’s hospital at Badami Bagh Cantonment in Srinagar. “My family had no idea where I was,” Trantray said. “Later, my parents and relatives were shocked to see me alive.”

After he recovered Tantray was sent to an interrogation centre at the Old Airport. “For six months, they were investigating me and when it proved I was innocent, they set me free. The government, much later, gave me an ex-gratia of Rs 25,000.”

Abdul Rashid, a labourer recalls hearing some gunshots, and within minutes army attacked the village. “They even fired on people who were trying to evacuate the injured to nearby hospital. I remember 13-year-old boy, Farooq Ahmad Bhat, who was killed while escaping from the fields.” Bhat was the only son of his parents.

A resident, who wished not to be identified, said he was barely 14-years-old when the tragedy hit their village. “The firing was indiscriminate and continued for more than 20 minutes and they targeted people directly,” he said. “I remember some of the females who tried to come in between were beaten.”

In 1990, the initial years of insurgency, crackdown or CASO was a new thing to Kashmir. However, before the massacre in Pazipora, Kashmir had already witnessed a series of massacres: Srinagar (17 people killed on January 8), Handwara (17 killed on January 15), Gawakadal (50 killed on January 21), Handwara (26 killed on January 25), Zakoora and Tengpora (33 killed on March 1), Islamia College Srinagar (70 killed on May 21) and Mashali Mohalla (9 killed on August 6, 1990).

But the one in the sleepy hamlet of Pazipora, which is divided into two parts, Payeen (lower) and Bala (Upper), was horrifying for its residents.

Another eyewitness account of the events says that a CASO was laid by forces in Pazipora Payeen during early hours. When the army men from Raj Rifles completed the exercise, they started moving back towards their garrison. When they reached Pazipora Balla, they heard some gunshots, leading them to cordon off the whole area. “People were unaware of what was happening,” the witness said. “Panicked, they started running towards another village and it was when they were fired at.”

A key eyewitness, Ghulam Nabi Mir, who lives in Zaloora village of Sopore, was posted as forests officer in the belt. Mir, locally popular as Nab Tscher, was a legend in the area of his posting. A Dabangg style forester who would roam around on a bike like a bird to ensure the fuel-wood collecting women do not damage the forest. He was a sort of terror.

But his presence and, more importantly, his presence of mind, saved many people. He stayed put till the last dead man was buried. It was his raw courage that led him to get into the local mosque and make a public announcement, asking people of the neighbouring villages to assemble for funeral prayers.

Now living a retired life, Mir’s memory has not faded a notch. “Early that morning, I went to the Kralpora Division office at around 10 am. I came back to my residential quarter. I did not see people around. It was a desolate place as everyone had fled from the village except a blind old woman who was crying,” Mir recalls. “I asked her details and she told me loot hasa gov (there was a plunder). I heard some gunshots too so I quickly wore my official uniform.”

As Mir moved out, he said, some soldiers aimed their guns at him. “They didn’t open fire at me because of my uniform that resembled that of a policeman. I wore a two-stars. My uniform saved me, most probably.”

By then, however, part of the village was already on fire. Mir said police team including that time concerned Station House Officer (SHO) Kupwara, Aftab Ahmad Kakroo and SHO Vilgam Shabir Ahmad Shah, besides, Fire and Emergency Services were stopped by the army. They were not allowed to enter Pazipora.

“I straight away went to the Masjid but its door was locked. I smashed it and got in, and made a public announcement,” Mir said as if he did it yesterday. “I addressed the army telling them that if they did not permit them in, they will be responsible for all the destruction in the village. After 15 minutes, they let them in.”

“I also requested the nearby villagers of Trehgam on public address system to bring first aid for the injured. A private medical team came and nursed the injured,” he said. “I counted 26 dead bodies. Even the Major rank officer was himself burning the houses. I also doused flames of many houses. Watching these heart-wrenching scenes, the SHO turned emotional and I felt as if he may do something untoward, I tried consoling him.” He said people from all age groups were killed and one girl was raped.

As if turning melancholic, the former forest officer said there was blood all around, screams for help and cries. “That was the last time when I heard moans of people before they breathed last,” he added. Tragically, Mir had his own share in the misfortune that Kashmir stands plunged into. Ghulam Haider, his son, a businessman, was brutally murdered in Srinagar and thrown in a sack in 2005. He still does not know why.

Mushtaq Ahmad, a witness, said 18 bullets were shot into the stomach of a youth who was detected “still breathing” after being recovered injured. “An entire carbine was emptied on the Farooq’s chest,” he said.

“Some pretended to be dead and thus survived.” He believes it was a scene from the war.

Ahmad still remembers their names: Ghulam Ahmad Lone (Balipora), Ali Mohammad Lone (Chek Pazipora), Ghulam Muhammad Beigh (Dar Mohalla), Shafi Khan, Nazir Ahmad Dar, Usman Ahmad Dar, Ali Mohammad Itto, Ramzan Mir and Muhammad Amin Masala – all residents of Pazipora. “The fact is the soldiers had gone berserk and created this doomsday,” he said. “I escaped miraculously.”

Recounting the moments Ghulam Mohiuddin, another local resident said he witnessed the first bullet hitting Abdul Rashid. “He got it in his head,” Ghulam said. “He was a patwari and he dropped down like a tree.” The second victim was Mohammad Munawar Dar, a resident of Kunan. “Munawar’s body was lying near the mosque wall. Though the firing was non-stop, I mustered courage and dragged Hayat’s body out.”

Manzoor Ahmad Dar was just a kid whose hand was held by his father when the firing took place. “I saw a bullet hit his abdomen but he didn’t leave my hand,” Dar said. “Later when he got another bullet on his chest, he released me saying – run away Manzoor, save your life. Those words still frequently echo in my mind and get me the nightmares.”

Some people who could not flee were so terrified that they hid in otherwise impossible spots. Shopkeeper Muhammad Maqbool Mir, who was barely 15 then, for instance, jumped up the chimney of his kitchen. “After three hours when forces left the village my mother came and dragged me down,” he said.

Mushtaq Ahmad had somehow accompanied the injured who were driven to Kupwara. “There was no place in the hospital. We brought the beds out of the hospital and placed them in the park. We started providing first aid to the injured, as the hospital staff was busy shifting the critically injured to Baramulla,” Mushtaq said. “Women and youth of the town were leading from the front in managing the injured.” Then, Kupwara had a small sub-district hospital.

One of the worst victims is still living – Sara Begum. She was home and still remembers how soldiers barged into her residence and shot dead her two nephews: Mohammad Yaseen Wani and Mohammad Shafi Wani. They were ordinary labourers but, that day, they had stayed home for some work not knowing death is going to knock at their door.

Zeba was witness to the killing of Bashir Ahmad Bhat, 22, a close relative, who was pursuing General Nursing Course at Srinagar and was on holidays. “They first took him out of his house and later killed him in front of my eyes,” Zeba said. “As I was pleading for his life, I was molested. Villagers came around and saved my modesty.”

Tragically, Bashir’s brother, Farooq – a school going student, was also killed in the same incident. Their relative Mohammad Jamal Dar, a mentally unsound person, was also killed the same day.

As the dust settled and new events of blood and destruction overtook Pazipora, many widows and orphans were left to face the world in destitution.

One of the victims was Farooq Ahmad. He was survived by a daughter and two sons. They were unaware of what had befallen on them and their mother. His widow Sara took the challenge and struggled bravely for the sake of her children. Farooq’s widow was pregnant that time when her husband was killed. Seven months later, Sara was also killed. “She was in the ninth month of pregnancy and was killed with the baby in her womb,” one of her relatives said. “She was killed by militants.”

Her two sons and their sister – without father and mother – were brought up initially by Sara’s mother. Later, they were adopted by their uncle Ghulam Nabi, who decided against marrying for the sake of his nephews. After many decades, they are living a proper life.

It was much later that the state government considered some of the families for government jobs under SRO 43. Residents said some families were “blatantly ignored.”

One SRO appointee is Ghulam Mohammad Lone, 48. A resident of Poshpora, still remembers when his father Ghulam Ahmad left for the Friday prayers. “He knew there were firing shots from the village but he did not want to skip his prayers. He was on his way to the Jamia Masjid walking through the paddy fields when four stray bullets hit his chest,” Lone said. “It was a boy from the neighbouring who came rushing and shouting – Mohammada Choon Maaleis Aav Fire”. Not able to do anything, he said he started crying.

Two years after he lost his father, a massive flood hit the Shungli Mohalla and washed away his home. He now lives in Babagund.

Shabir Ahmad Shah, the police officer who reached the spot from Viligam as part of his duty said some militants had fired upon the army from a far off place without causing any damage. They reacted to this firing and killed people. He was the first person from the state government to reach the site of carnage.

“SHO Kupwara along with his team took the 25 dead bodies and handed them over to their respective families in the evening in my presence,” Shah said. “These included an old man and an old lady. The lady had her sandals in her hand indicating she was fleeing from the harm. All the killed persons were civilians.”

The officer insisted that “there was neither any collateral damage nor any molestation.” He admitted the army had rounded up many people but after the police reached the spot, they were freed. “This is the fact that police, ambulances and firefighters were denied entry initially,” the officer, now retired, said. “As I reached the village the damage had already been done.” Terming the incident “unwanted and unwarranted”, the official said had he and his team not reached the spot quickly, the situation might have been worse.

Shah said his presence on the spot at the most crucial time of the belt was key to policing in the area later. “Those were the days when the police did not matter at all,” Shah said. “But for many years the mere presence of the police in the belt was because of the goodwill that my team’s work had generated that day. Otherwise, militancy was so fierce that barely anybody from the government would function.”

The massacre sparked widespread protests across Kupwara forcing authorities to impose a curfew to diffuse the volatile situation. But nobody knows anything about the follow-up to the police case that was registered.

Confirming that a case was registered in August 1990 when some villagers came to police station and informed the police station about the incident. He said the case has been forwarded to the home department for further investigation and actions. Police did not offer any details beyond this. “There have been two cases, one on basis of the army’s application that they were fired upon,” one official said. “The other was about the civilian killings.”

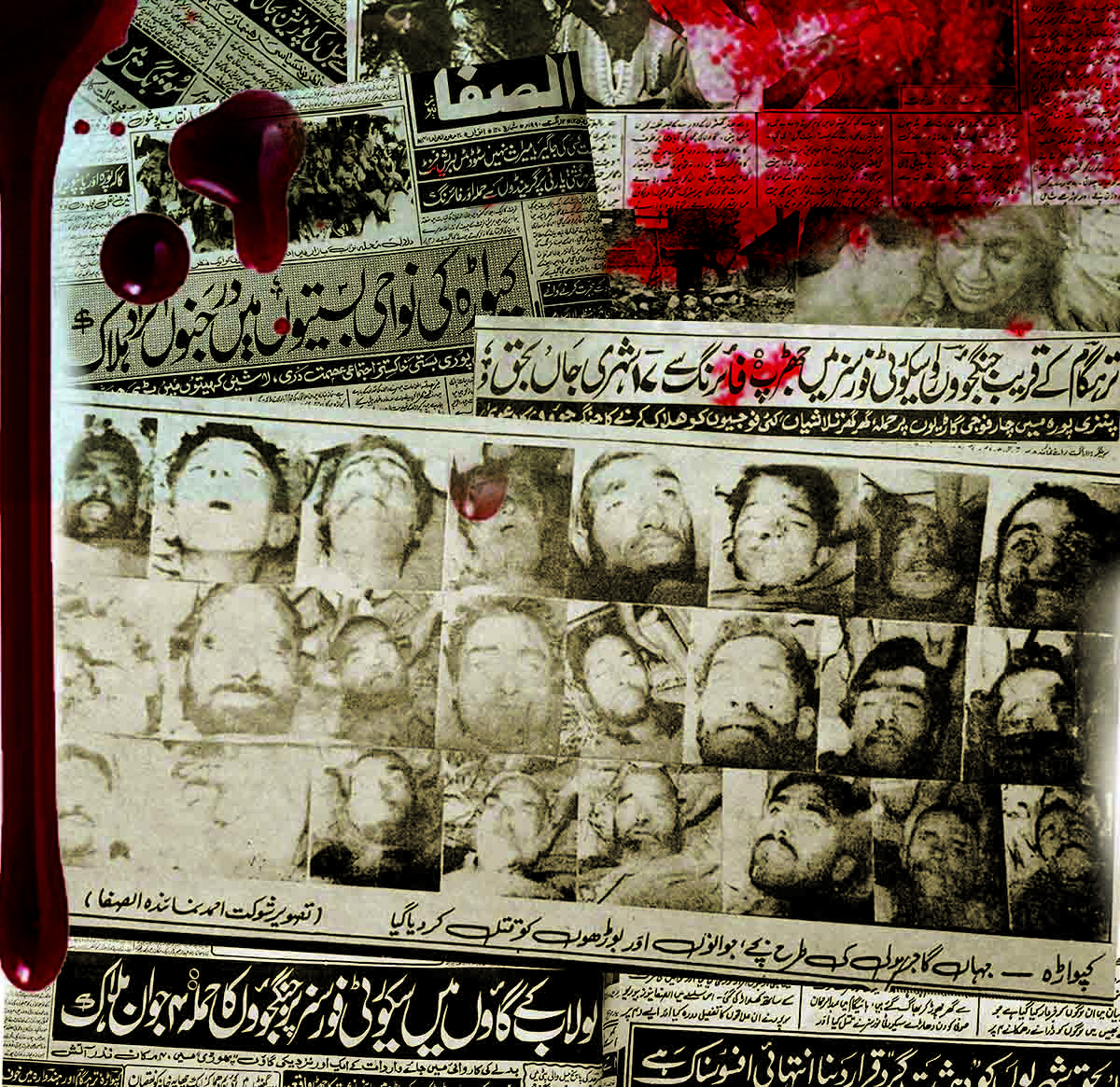

That day, Ghulam Nabi Khayal who was part of a large number of scribes who visited the spot, wrote, that the Akashvani and the Doordarshan had reported that the civilians were killed in the cross firing.

(Some names have been changed on request to protect their identity)