While Kashmir is expected to wait for its own elections, it was literally a key factor in the elections of Haryana and Maharashtra. Thanks to the abrogation of its special status, now Kashmir is emerging a major issue for the British elections too, reports Saima Bhat

History is all about circles that start where it ends. Britain was the primary force that led to the creation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir when the East India Company sold Kashmir to Jammu warlord Gulab Singh in 1846. A century and a year later, it fled the Indian subcontinent after leaving Kashmir as a burning problem between India and Pakistan.

Seven decades later, as Jammu and Kashmir was undone as a state and bifurcated into two federally governed Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir on August 5, UK is now facing the Kashmir heat. In certain parts of the island country, Kashmir will be a key-deciding factor for the House of Commons election on December 12. Many see the phenomenon as “poetic justice” as the country accused of creating the mess is finally facing the music.

Kashmir’s importance in UK owes to a huge population having origins in India and Pakistan. Against 1.5 million British Indians, there are close to 1.2 million British Pakistanis. The Birmingham city mostly belongs to Mirpuri Kashmiris. Delhi had to use its diplomatic channels to get October 27 rally for Kashmir cancelled in London and the Scotland Yard imposed Srinagar-style restrictions to deny protests.

Unlike ruling Conservative Party, the Labour Party is in sharp focus as its India and Pakistan origin leaders are divided on Kashmir. Recently, the party started yielding to the pressure by Indian diaspora and agreed to change its stance on Kashmir. This was the outcome of the “do not vote for Labour” campaign that Indian diaspora launched recently, a move that could help the Conservatives.

The Start

In its yearly conference at Brighton, the Labour Party passed a resolution on September 25, supporting international intervention on Kashmir and a call for UN-led referendum. Apart from condemning the revocation of state’s special status, the resolution asked the party to support Kashmir’s right of self determination, call for sending international observers and intervene at the United Nations Human Rights Council.

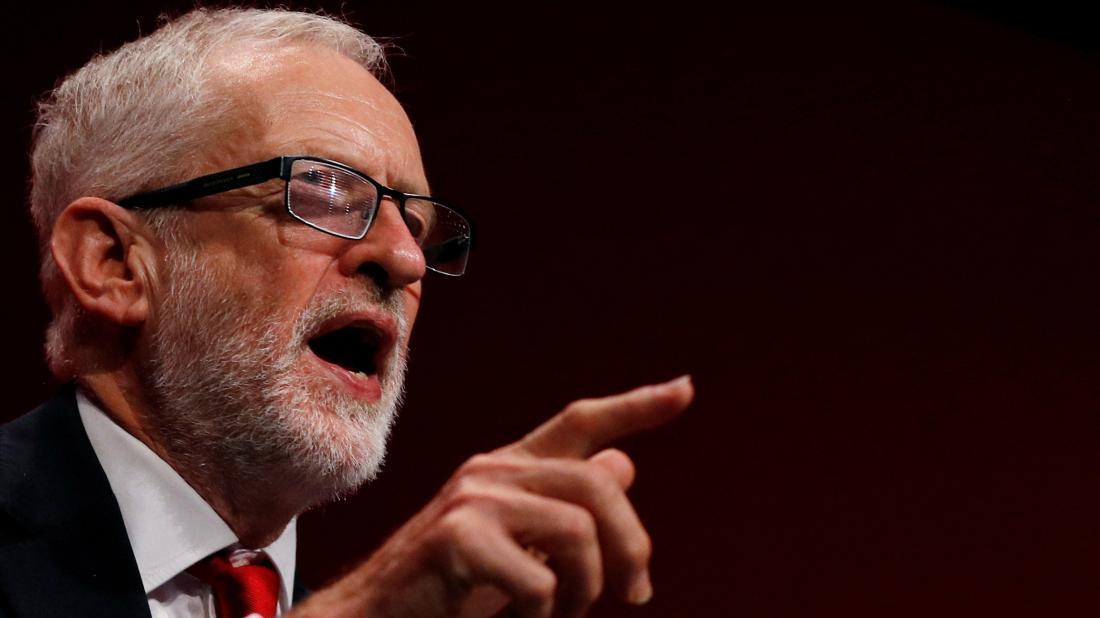

The stand of the Jeremy Corbyn led party was in sharp contrast to the Conservative Party government that said the issue is bilateral between India and Pakistan. Earlier, Corbyn had tweeted about the state of human rights in Kashmir on August 11, and many of his party leaders participated in anti-India protests on August 15.

The Kashmir resolution was moved by party leaders representing Blackburn, Dudley North, Keighley, Stockport and Wakefield CLPs. British-Pakistani leader Uzma Rasool initiated it and Labour MP Naz Shah seconded it.

Delhi reacted quickly. Indian High Commission in London cancelled the yearly reception with the party leaders. “Government has noted certain developments at the Labour Party Conference on 25 September pertaining to the Indian State of Jammu & Kashmir,” MEA spokesman Raveesh Kumar said. “We regret the uninformed and unfounded positions taken at this event. Clearly, this is an attempt at pandering to vote-bank interests. There is no question of engaging with the Labour Party or its representatives on this issue.”

Diaspora Takes Over

Labour Party’s prominent members of Indian-origin started a follow-up quickly. Labour Friends of India (LFIN) sent a letter to Corbyn and shadow Home Secretary Emily Thornberry protesting against the procedure followed in the passage of the emergency motion. The letter asserted that abrogation of Article 370 was an internal matter of India. “Issues of sovereignty are a matter for the Indian government; border issues are matters for the governments of India and Pakistan,” Indian- origin MP Keith Vaz, who is facing a half year suspension for disregarding the law, said in the letter.

Other Labour MPs including Virendra Sharma and Barry Gardiner also expressed, “disappointment” over the resolution.

Initially, the Labour Party strongly refused to recall the resolution and insisted it was in the democratic spirit of the party. Corbyn defended the resolution personally. “The emergency motion on Kashmir came through as part of the democratic process of the Labour party conference,” Corbyn wrote in response to the complaining MPs. “However, there is a recognition that some of the language used within it could be misinterpreted as hostile to India and the Indian Diaspora. Labour understands the concerns the Indian community in Britain has about the situation in Kashmir and takes these concerns very seriously. The Labour Party is committed to ensuring the human rights of all citizens of Kashmir are respected and upheld. This remains our priority and I agree that we should not allow the politics of the sub-continent to divide communities here in Britain”.

But the Indian diaspora did not stop reacting. Almost 100 British-Indian outfits had assembled in one Twitter handled with the sole aim to undo the resolution. The most recent was the “do not vote Labour” campaign launched by Kuldeep Singh Shekhawat, who heads the Overseas Friends of BJP. The fierce campaign has started dividing the Hindu Britons as there are reports in British media that some of the Conservative politicians are encouraging the campaign. At least two Hindu groups have decided not to invite Labour leaders thus preventing them from explaining themselves.

Indian diaspora says it holds a million odd votes. Reports appearing in British media suggest the Tories (Conservatives) are traditionally getting better vote share from ethnic Indians – 30 per cent in 2010 and 40 per cent in 2017. Balance 60 per cent votes have traditionally been going to the Labour Party.

Climb Down

The Brexit has already run riot with the British politics. People’s priorities are changing quickly. A recent poll published by The Independent suggested that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party is gaining ground in comparison to the Labour Party. In a month, the newspaper said, Conservatives improved from 31 to 37 per cent and Labour support dropped from 29 to 26 per cent.

Though this has nothing to do with Kashmir but Labour has started quick-fixing. On November 11, Ian Lavery, the Labour Party Chairman, issued a letter that is being seen as party’s climb-down on Kashmir.

“Kashmir is a bilateral matter for India and Pakistan to resolve together by means of peaceful solution which protects the human rights of the Kashmiri people and respects their right to have a say in their own future,” the letter reads. “Labour is opposed to external interference in the political affairs of any other country. As an international party, our concern is to ensure respect for the human rights of all people in the world, regardless of where they live.”

The letter has acknowledged the “sensitivities” expressed by the Indian origin leaders. “We recognise that the language used in the emergency motion has caused offence in some sections of the Indian diaspora, and in India itself. We are adamant that the deeply felt and genuinely held differences on the issue of Kashmir must not be allowed to divide communities against each other here in the UK,” the letter reads. “The Labour Party will not adopt any anti-India or anti-Pakistan position over Kashmir.”

But this is unlikely to make British politics skip Kashmir. Birmingham based Tehreek e Kashmir leader Raja FahimKayani has asserted that “Kashmir issue is the deciding factor in voting here.”

Kashmir In Air

Politics apart, Kashmir has emerged very important in the public discourse. Events about Kashmir are routinely taking place. The most recent event was The Cost to Britain of the Kashmir Crisis: Is There a Solution?, a debate at the security think tank Chatham House, organised by strategic advisory firm CTD Advisors. The event was organised by AbdurrehmanChinoy, a British Pakistani businessman, who also heads the Queen Mary Pakistan Society.

There, Sir Mark Lyall Grant, a national security adviser to former British Prime Ministers Theresa May and David Cameron said that unless Kashmir is solved, UK would face “rising extremism” because 60 to 70 per cent of British Pakistanis’ are from Mirpur, a Kashmir district. He said the revocation of special status was likely to lead to greater extremism in the region. “Therefore there is a risk of radicalisation in this country of British Kashmiris,” The Independent quoted Lyall saying. “We all know that diasporas tend to be more radical than communities left behind and I do not see why this should be any different.”

Grant said Kashmir was the story of missed opportunities; the last one was the failure of Agra Summit. “The political stars never quite aligned but a solution similar to the Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement, with a soft border allowing locals to travel freely from one part of Kashmir to the other, will have to be the outcome of any peaceful solution,” Grant was quoted saying, insisting only India and Pakistan can do it.

Asserting that UK alone will have to manage costs worth US $20 billion in case of an India Pakistan conflict, Grant, in a piece that he wrote for Forbes said: “The UK has a particular responsibility – when the British partitioned India in 1947, in their haste to leave the subcontinent, they failed to tackle the well-known differences over Kashmir, thus creating an explosive bone of contention between India and Pakistan that has plagued the region ever since.”

Speaking at the same function, Jack Straw, former foreign secretary, said Modi’s revocation of special status was “outrageous, preposterous, a complete breach of human rights and without any strategy attached”. But he asked Pakistan to withdraw its claim to Kashmir because the “completely unobtainable, impossible” goal has led to Pakistan sponsoring terrorism and bloated her defence spending. He asserted: “The thing I am clearest about is the way in which the whole of Pakistan’s politics and economics has become distorted in this vain search or attempt to redraw the boundaries of Kashmir and to take Jammu Kashmir into the Pakistan Republic.”

In her intervention, Pakistan’s former UN ambassador, MaleehaLodhi suggested, “international community must stop being a fire brigade and intervene to find a peaceful solution”. NDTV’s NidhiRazdan was highly critical of Pakistan but also mentioned the Kashmir lockdown situation. “Sadly, the people in whose name these changes [revocation of the special status] took place were not consulted,” Razdan was quoted saying. “The political leaders who carried the Indian flag all these decades are in detention. All this hardly burnishes India’s credentials as the world’s largest democracy.” Back home, the broadcast journalist was trolled for some of her comments at the event.

There are activities taking places in other places across Europe. Almost a fortnight after some EU parliamentarians had a sponsored visit to Kashmir, the Pakistani side is reportedly organising events to neutralise the possible impact of the visit that literally backfired. Brussels, according to Pakistani media, observed 12th Kashmir-EU Week in the European Parliament (EP).