Son of a British army officer, Henry Walter Bellew (August 30, 1834 – July 26, 1892) was a doctor and East India Company’s top Afghanistan expert. In 1873, he was despatched to Kashgar and he spent August in Srinagar, understanding its people and ruler, Maharaja Ranbir Singh. In the first of the two-part series, Bellew details his journey from Baramulla to Srinagar and the people living around

Soon after our arrival at Pattan we received a visit from Diwan Badri Nath, a high official of the Kashmir court, who, on the part of his Highness the Maharaja, welcomed us to Srinaggar, and delivered the friendly messages he was charged with an innate suavity and politeness of manner quite charming in themselves, and the more appreciable, because they were not mere empty words, as the arrangements for the comfort of our march thus far abundantly proved.

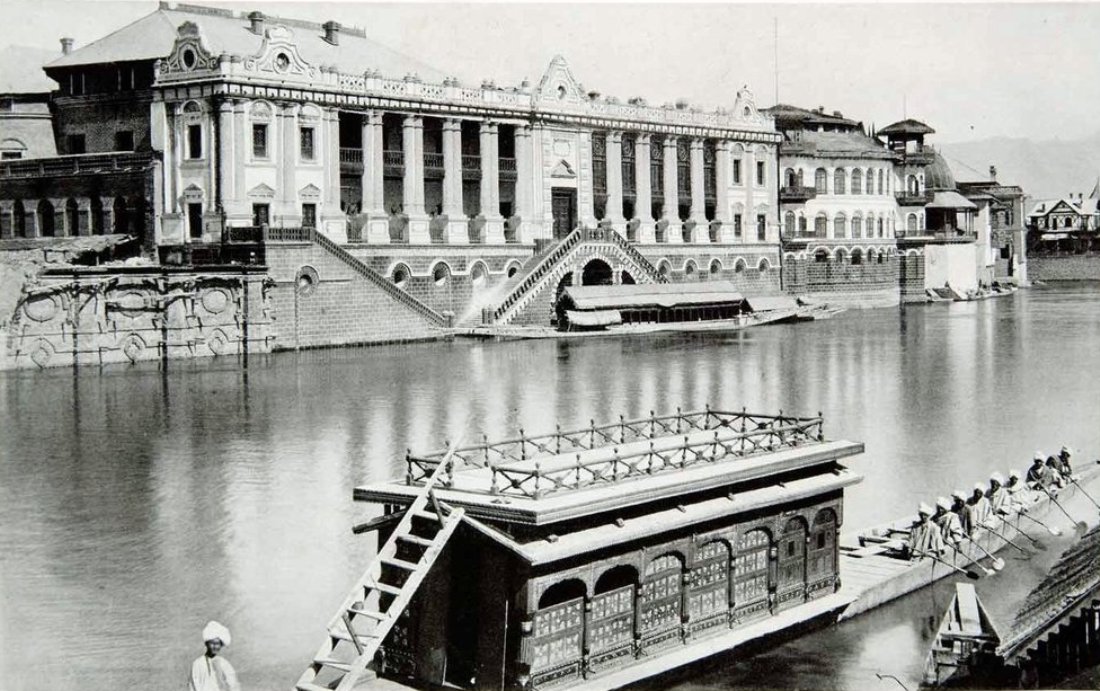

In the afternoon I accompanied Colonel Gordon to return his visit, and next morning they rode off together in advance to select a site for our camp, which is to halt some days at Srinaggar to equip our men and cattle with warm clothing for the journey across the passes. We followed with the camp next morning, and on arrival at the river-bank below the city were met by Pandit Hira Nand, chief of the city police, who was awaiting us with one of the Maharaja’s state barges to convey us by water to the Nasim Bagh, where Captain Biddulph’s party was camped.

Captain Chapman and I accordingly took our seats on the chairs set for us under the canopy of the pinnace, and were paddled up to our destination by thirty boatmen, whilst the camp, crossing at the first bridge, followed the land route, and joined the advance party under Captain Biddulph, whose camp we found pitched on the shore of the Dall lake, under the shade of the plane trees of the celebrated park here laid out by the Emperor Akbar the Nasim Bagh.

The trip up the river was a very agreeable change, particularly in the gorgeous and swift conveyance which had been so very thoughtfully provided for us, for the march was a long one, and the sun nearing the meridian was growing uncomfortably strong. And it was no less interesting on account of the excellent river view of this remarkable city which we were enabled to enjoy from the shelter of the open pavilion in which we were seated. It was an oblong chamber built up in the centre of the boat, and highly decorated in that intricate pattern peculiar to the artists of Kashmir, and so well-known for that marvellous blending of colour which, without disturbance of harmony amongst all, presents a groundwork of either according to the light in which it is viewed. The shallow vaulted roof was supported midway by pillars which divided the chamber into two compartments and at the sides by others which were fitted for shutters to close the whole when necessary.

The weather being fine we found these last had been removed, and consequently, the roof, supported on its pillars alone, formed a canopy or pavilion open on all sides above the panel of the basement.

The scene on either bank, as one is borne along through the midst of the city, is bewildering by the variety and the novelty of the sights that catch the eye at every turn; yet there is a sameness that pervades the whole, and characterises it as essentially local.

The succession of bridges, under whose spans of creaking and trembling logs for arches they are not to be called our boat was shot with a speed against stream hardly less than that of the more humble craft coming down with it, are all members of one family; each a singular repetition of the other, and all alike in their tumbledown look, and peculiar structure, and decayed appearance. The boats, too, which float amongst them, our own not excepted, in all their different sizes and various fittings, are of one shape and one resemblance.

Whether it be the light and painted state-barge, or the ponderous and unadorned rice-boat; whether it be the swift pinnace with its elegant canopy and many paddles, or the more leisurely travelling-boat, with its mat roof and mud-built cooking range; or whether it be the skiff of the fisherman and fowler or the punt of the market-gardener and caltrops-picker, they are all of one pattern and one build a flat keel less bottom, straight rib less sides, and tapering ends that rise out symmetrically fore and aft, prow and stern alike for advance or retreat.

Of such form, these boats are well suited for the conveyance of heavy burdens on a smooth stream; but they are most dangerous craft on rough water. From the wide hold they take of the water they gain buoyancy in respect to freight, but they lose it in the matter of riding. Instead of rising over the waves they present an obstacle over which they break, and the surf pouring over the low sides soon swamps the vessel.

The natives rarely venture far away from shore in heavily-laden boats, and when crossing the Wolar lake usually coast along its sides so that, if perchance caught by one of the squalls which so often sweep its surface, they can run as to a safe port into the belt of weeds bordering its shores; for here the water-lily, duckweed, and caltrops, with other aquatic plants, cover the water with a continuous spread of broad leaves which float on the surface and prevent its being disturbed by the wind.

The mass of houses built on the masonry embankments which rise out of the water on either hand and display here and there amongst the varied components of their structure the chiselled blocks of some ancient palace or temple, incessantly draw the eyes from side to side by the attraction of some new form, and present a spectacle no less novel in character than strangely diverse in its uniformity as a whole.

The gable roofs, with their untidy thatch of beech bark and their attic lofts open at both ends, rest so insecurely upon the loose-jointed frame of upright poles they cover that they seem ready to fly away with the first gale of wind, and certainly constitute the most peculiar feature of the architecture everywhere. Whether on the king’s palace or the peasant’s cottage, on the merchant’s store or the mechanic’s shop, or whether on the Hindu’s barrack or the Musalman’s mosque, this draughty log-built roof is the same in character on all.

The edifices it surmounts present a greater variety of structure, though in all except in the palaces and Hindu temples, which are built throughout of solid masonry the framework of upright poles fixed upon a raised platform of masonry forms the skeleton. This framework is held together by cross-trees and rafters and closed in, tier above tier, either by a planking of rough-split logs or a thin wall of bricks and mortar. The interior partitions are of lath and plaster, and the compartments are lighted very much less than they are ventilated as many a tourist in the “Happy Valley” must have discovered to his cost in comfort by those lattice windows, so rich in the variety and elegance of their designs, which are, with the carved woodwork of the portals, the most agreeable features of Kashmir architectural decoration; so far at least as exterior appearance is concerned, for the matter of interior comfort is quite another consideration, and dependent for its merits upon the views or means of the occupants.

Glass windows are unknown out of the palaces and the mansions of the wealthy. The lattice window supplies their place, and how inefficiently may be readily understood when one learns that the only device adopted for keeping out the wind is a sheet of paper pasted over the fretwork, whilst the cold air pouring in over the open coping is considered out of reach and submitted to as a matter of course.

The very general use of timber for house-building in Kashmir, and the loose putting together of the beams and logs, is said to be necessitated by the frequency of earthquakes in the country. It seems, however, that other causes are not without potent influence in determining the preference. And notably the character of the people for physical inactivity, a trait, which is exemplified in the nature of all their industries.

Their shawls and embroideries, their silver work and papier-mache-painting, their stone-engraving and woodcarving, &c., all alike exhibit proofs of wonderful delicacy and minute detail, but tell of no active expenditure of muscular force. Where this is required, as in house-building, we find it exercised only to the smallest extent absolutely indispensable for the attainment of the object desired. Hence, though stone is abundant and more durable, the easily-felled and floated timber is put together in a style of unfinish altogether independent of adaptation to stability under the conditions assigned.

Doubtless the humid character of the climate and the soft nature of the soil may have their share of influence, which must not be overlooked. But with the relics of ancient edifices of ponderous stone and the existing buildings of substantial masonry before us on the spot, these conditions, it would appear, offer no serious obstacle to a more finished and substantial style of architecture to that which is in vogue here. Such as they are, however, the houses of Srinaggar constitute the most prominent feature in the view of the city as seen on the way up its stream. And more special objects amongst them are the new houses rising on the river frontage very welcome signs, in their elaborate finish and straight angles and neat lines, of the march of civilisation and adoption of modern improvement ; the lofty piles of its principal mosques topped with those peculiar belfry-like towers supported mid-roof testimonies to the architect’s recognition of the dictates of taste as superior to the claims of conventional form; and those shapeless little idol temples of stone and mortar which, though in the front rank on the river’s bank, would be passed unnoticed but for the glare of their tinsel and gilt incongruous objects in this quaint jumble of woodwork structures. It remains to fill in the picture with man, whose presence and activity enliven the scene and complete the speciality of its character. In a city so well situated as a centre for the trade of the countries beyond the passes, one might naturally look for the representatives of the different surrounding regions amidst the crowd of its inhabitants, but they are not to be found or at least they do not appear amongst the moving forms that pass before the eyes of the mere traveller in anything like the number expected.

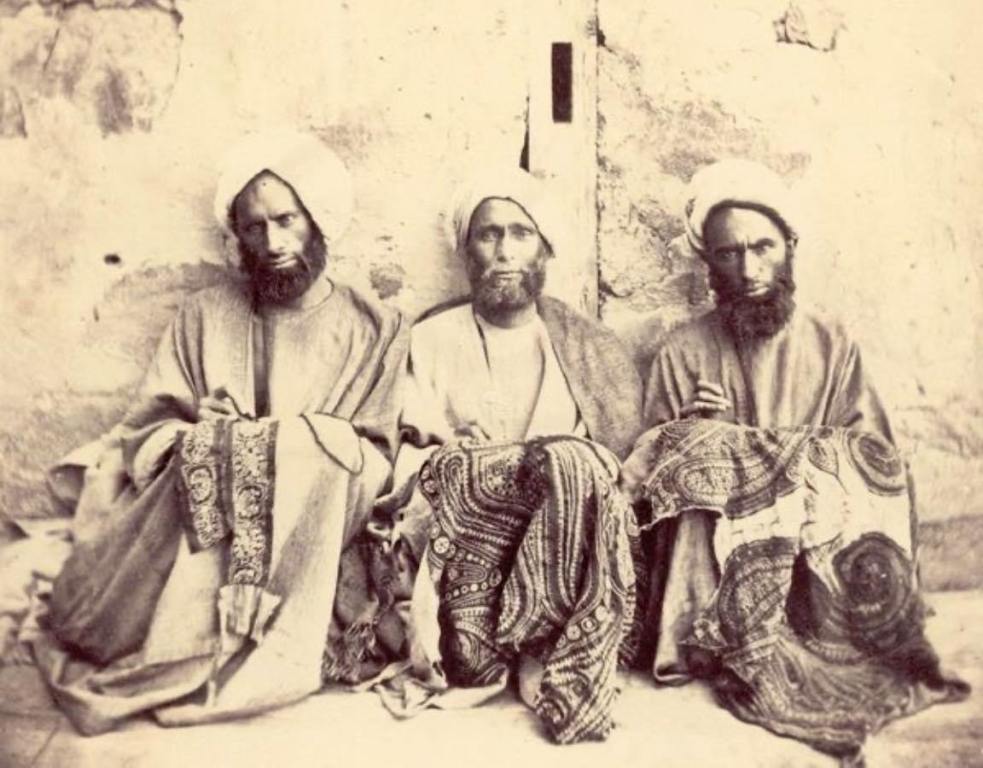

As it is, the familiar forms of the Afghan and Sikh, met here in so frequent recurrence, claim no such interest from us as do those of the people the one ruled in this valley not so very long ago, and the other rules at the present time. Nor do the few members of those little known tribes of the outlying districts of Dardistan, Baltistan, and Bhotan who are found here as government servants, more than excite a transient curiosity amidst the crowd of natives which more fully attracts the attention. It is the Hindu Pandit and the Musalman Kashmiri who are the chief actors in that busy scene of life and activity which at this season meets the eye at every turn in the river’s course.

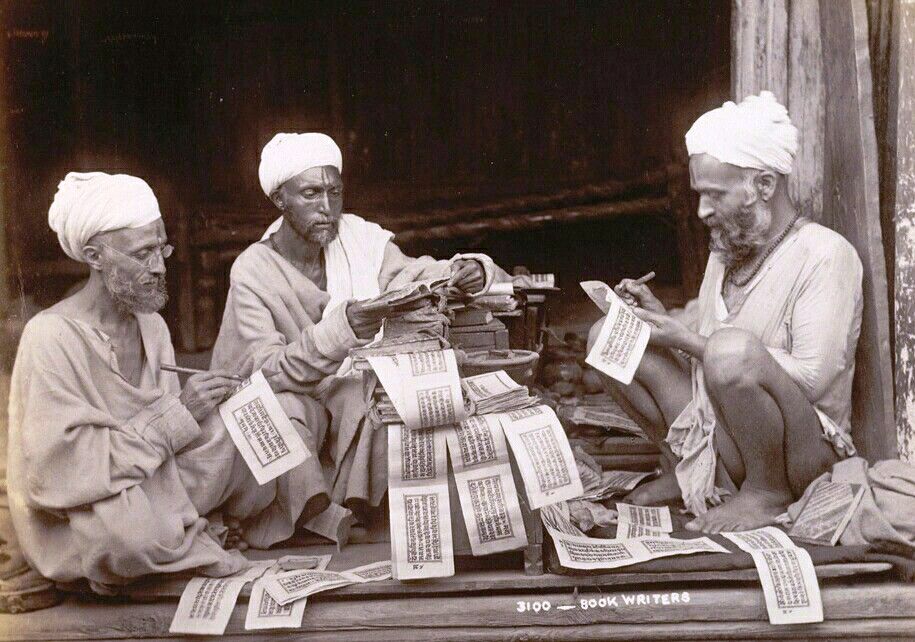

The Pandit, or Batta as he is styled by his Muhammadan brother, if not recognised by the nicer distinctions of manner and speech, or the difference in dress and occupation, may be at once distinguished by the paint-marks carefully set on the forehead as the tokens of his religious purity.

He is seen as the well-to-do merchant, with a party of his fellows passing up and down the stream, seated on the matted floor of the Srinaggar gondola, in animated chat on the concerns of his business; his comfortable form bulging between the tight strings of his spotless linen, and enveloped in the loose folds of his soft warm shawl. Or he is found en dishabille performing his ablutions, immersed at the edge of the current under which his shaven head, with its lank crown-top lock, bobs now and again as he gabbles through the formula of his prayers; his hands the while, held up to the sun, pouring back to the river the drops they had raised from it, or quickly passing through the fingers the threads of janeo, which encircles his body; unmindful alike of the presence of the stranger or the proximity of his womankind the reputed fair Panditani who (the latter), in like undisguise, may be disporting herself in the same element, or, concealed within the ample folds of her shapeless gown, may be washing her linen or filling her pitcher at the brink. Or else he is observed as the Brahmin priest his withered and emaciated form divested of all covering but the indecent loin-clout seated on his hams cooking his simple fare of unleavened cakes and pottage, and guarding scrupulously the purity of the spot sanctified for the operation; or, seated cross-legged at the door of his temple, he is reciting the shastar with a volubility equal to the swaying to and fro of his body; or else, motionless and silent, he is absorbed in a trance of meditation, or more probably of mental torpor and abstraction. Or lie is seen, writing-case and paper in hand, as the civil functionary the scribe, the notary, or the tax-collector in the pursuit of his special avocation, or, as the corn chandler, on the river-barges superintending the discharge of rice into the government granaries, or its sale to the people.

The Kashmiri, or Kashuri as he styles himself, constituting the bulk of the population, presents a greater diversity of ranks and occupations. These, from the barely clothed cooly and poverty-stricken peasant to the richly clad merchant and wealthy proprietor, are all to be seen in the course of a tour through the water-way of the city. The silversmiths, lapidaries, papier-mache artists, shawl-weavers, silk embroiderers, and other artificers are, of course, only to be seen to advantage in their workshops on either side of the river.

Here we are concerned only with the scene on its banks, and they consequently need no further notice in this place beyond the mention of their general resemblance in outward appearance to the Hindu portion of the population, from whom they are sometimes, in the absence of the paint-marks; tika, only to be distinguished by the different folding of the turban.

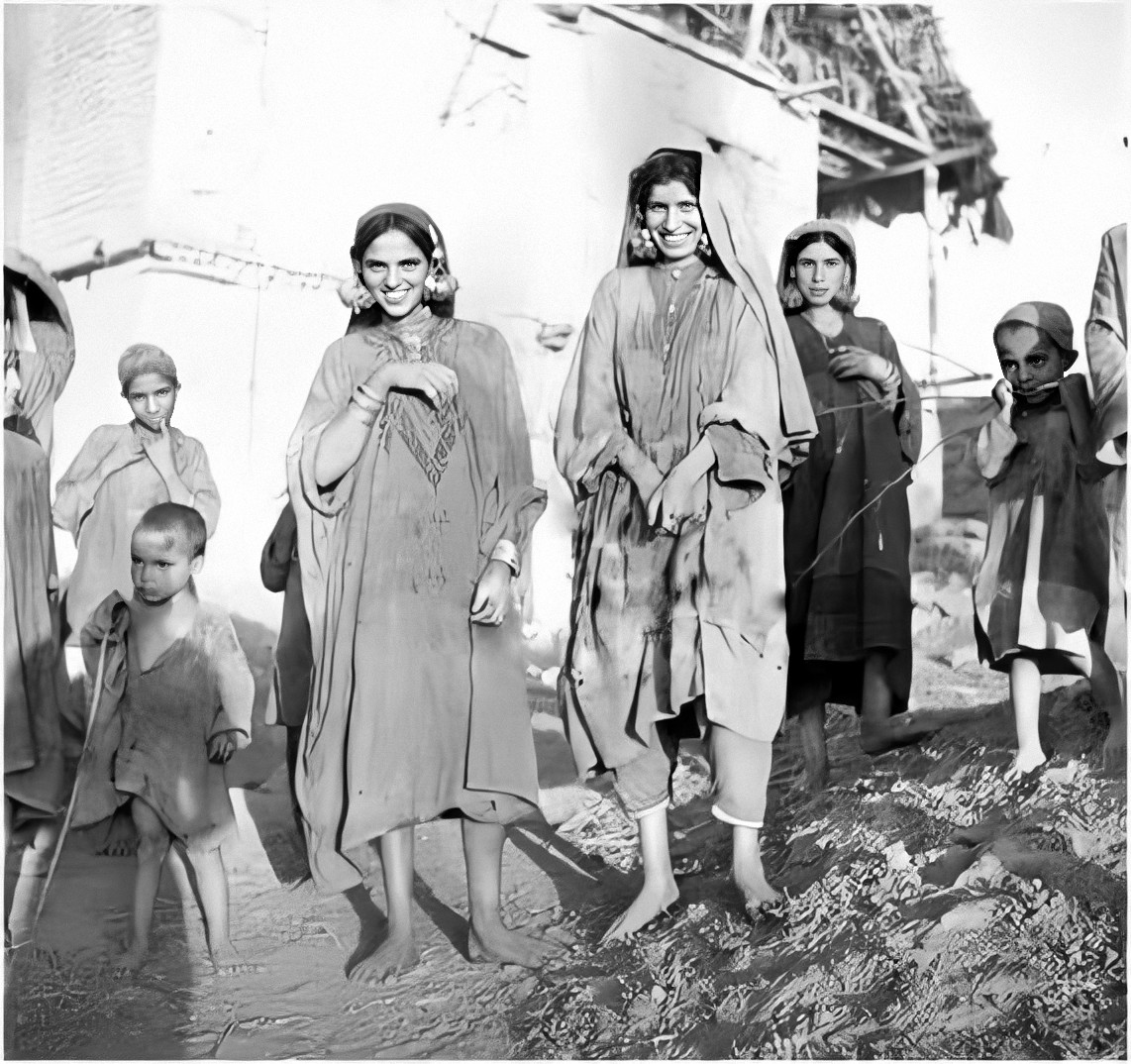

The special actor on the river- scene is naturally the boatman. His lithe, active form bared for the task is seen everywhere as it bends to the rapid strokes of his paddle; and his merry voice, too often raised in unseemly wrangle and vociferous vituperation, is heard above all other sounds. His family, who live in the boat with him, are seen variously occupied upon the banks; the children remarkable for their bright eyes, and soft, pleasing features disporting themselves on the limited planking of their homes moored alongside; whilst the mother and elder daughters are busy on the beach in that laborious and unsightly task of husking their daily modicum of rice. The loose-sleeved and very roomy shift, which, like a long nightshirt, covers the body from neck to foot, and forms, with the characteristic cap of red fillet, their only dress jerking up and down as their arms ply the pestle upon the grain is not the least strange sight of the many that here amuse the visitor. And this particular one, from the awkwardness of the implements the pestle being nothing but a pole of wood rounded at each end, and the mortar a mere cup excavated in a clumsy log of the same material suggests reflection on the apathetic character of the people, who with such an easy command of water-power can tolerate so burdensome a task.

It was through such a scene as this, the main features of which I have attempted to delineate by words that we passed on our way to the Nasim Bagh. The last part of our route wound through that series of canals which intersect the swamps lying between the city and Dall lake. They are at this season nearly choked by the abundance of the water-weeds that shoot up from their shallow bottoms to mature their fruit on the surface, and wither and rot; whilst their tangled meshes obstruct the passage, and poison the air with the stench of the mephitic odours evolved from the festering mass of their luxuriant foliage.

Between these narrow channels are small blocks of water-logged land, on which stand the log-huts and orchards of the market gardeners who supply the city with vegetables. They rise little above the level of the water, and are divided by cross trenches into fields, or plots whose banks are lined by rows of willows. Between these banks, which are further supported by stakes, and raised above the general level by heaps of the decayed weeds drawn from the bottom of the canals, the little skiffs of the cultivators ride their way over the mass of reeds concealing the passage from the eye of the stranger, and thus pass from one end to the other of this pestiferous tract of a labyrinthine swamp.

The produce of these gardens are cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, and tobacco, and that of the canals and shores of the lakes which is spontaneous are the water caltrops or singhara the fruit of which forms an important item as a breadstuff in the food products of the country, and is under government protection and the nidar, or root-stalk of the water-lily (whose beautiful pink flowers are the panpawsh of the Dall lake) which is largely consumed as a vegetable. Passing beyond these canals, we entered the circular pool, called the Dall, by one of those clear passages between the reed beds which stretch across its centre, and came upon the floating gardens.

These are formed of strips of decayed weeds which have been fished up from the bottom of the lake by means of a pole dexterously twisted amongst their long fibres.

They are staked to the bottom where they float by long poles, and are covered above with small heaps of earth in which the melon seed is sown. They are capable of supporting the weight of two or three men at a time; but great caution is necessary to prevent the feet breaking through their flimsy, rotten structure.

On the lake we found a number of little skiffs, each with its single occupant, dotted about the surface.

Here, in the line of our route, were two or three weighed down with the pile of weeds their owners were poling up from below for the repair of their floating melon beds, or maybe for the formation of a new one. There, along the shore, were a whole bevy of women, each paddling her own canoe with the one hand, whilst the other was rapidly plucking the duckweed that overspreads the surface, and throwing it into the hollow behind her with an eager haste, as though there was not enough to meet the wants of all. It is a favourite fodder for cattle, and is said to improve the milk of kine fed upon it. Further away, on the calm, open surface of the lake, rode motionless three or four boats as if moored to so many stakes, whilst the occupant of each, reclining crouched up, composed himself, head resting at the post, for a mid-day nap. Their occupants were fishermen, and far from asleep, were watchfully looking down the shaft of the narits or harpoon they poised in one hand to spear the first fish passing beneath its prongs.

We now came abreast of the handsome mosque of Hazrat Bal, the favourite resort of holiday folks, and passing its village, and the long array of bathing-closets half submerged in the waters of the lake, were presently landed at our camp a little beyond. Here, on the 4th August, we rejoined our comrades who preceded us from Murree.

Shortly after our arrival in camp, Wazir Ram Dhan made his appearance, attended by a long retinue of servants bearing the various comestibles of the dali or “entertainment” sent by the Maharaja. The Wazir set them in array on the turf in front of Colonel Gordon’s tent, and welcoming us to Kashmir in the name of His Highness, made the customary health inquiries, and expressed a hope that the arrangements made for our march were such as met approval.

The dali comprised a number of sheep and fowls, and dozens of great pottery jars of rice, and flour, with sugar, tea, fruits, and spices, and butter and kitchen stuff of sorts in liberal proportion. They were disposed of in the usual manner that is, for the most part, shared amongst our servants and our visitor dismissed with compliments and grateful acknowledgements to his master.

(The passages were excerpted from Kashmir And Kashghar – A Narrative of The Journey of The Embassy To Kashghar In 1873-74 by H W Bellew published by Trubner & Co in 1875. Read the second part here.)