Son of a British army officer, Henry Walter Bellew (August 30, 1834 – July 26, 1892) was a doctor and East India Company’s top Afghanistan expert. In 1873, he was despatched to Kashgar and he spent August in Srinagar, understanding its people and ruler, Maharaja Ranbir Singh. In the last of the two-part series, Bellew details his interactions with the ruler and a Haj pilgrim he found a guide in

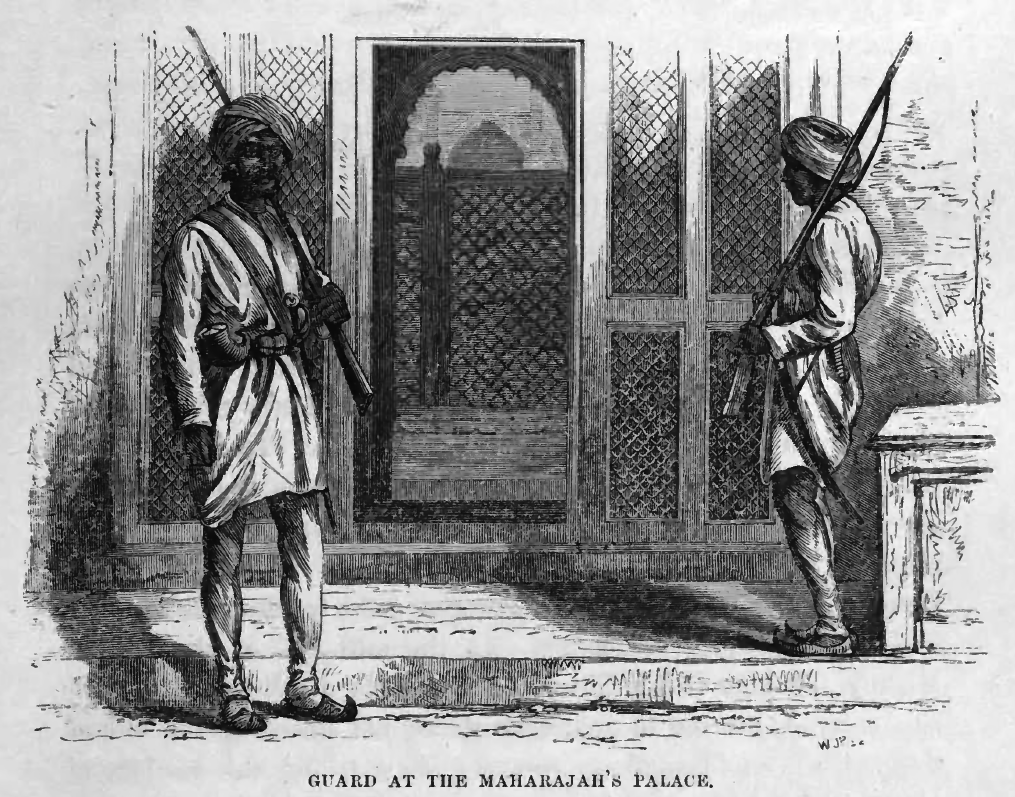

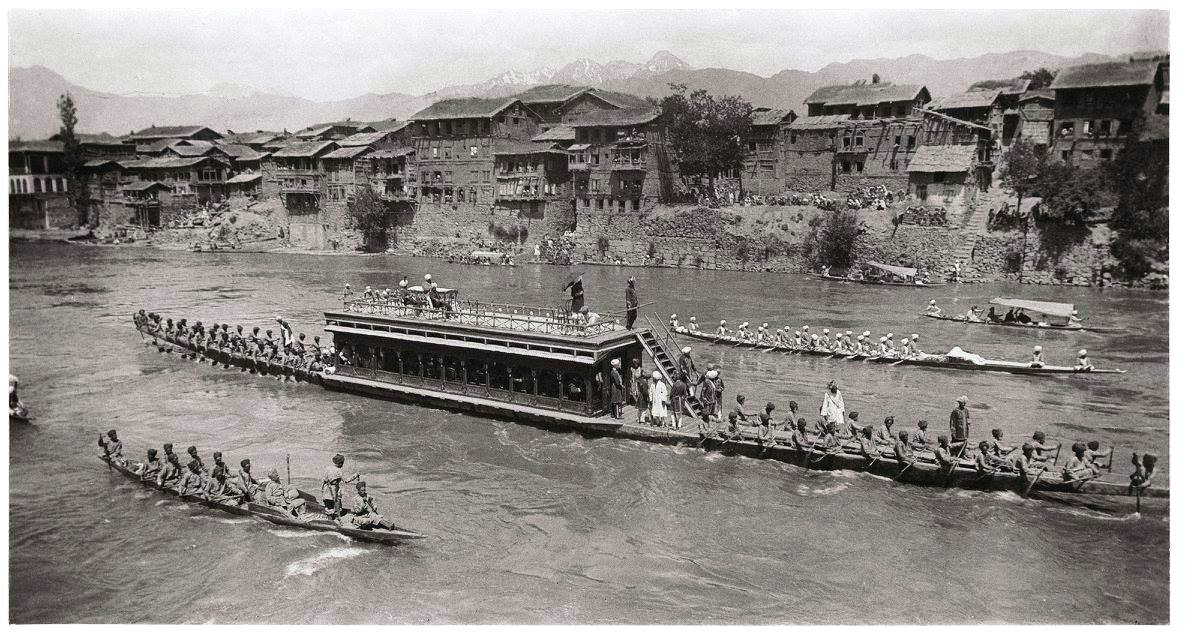

Next day, according to the arrangement by the Resident, Mr Le Poer Wynne, we proceeded to visit the Maharaja. At five o’clock in the afternoon his Prime Minister, Diwan Kirpa Earn, arrived in our camp, and after a ceremonial visit conducted our party to the palace in the Sher Garhi Fort, whence a pinnace of the kind called parinda, or Flier, from its rapid progress, had been sent for our conveyance.

Maharaja Ranbir Sing met us at the door of the terrace overlooking the river on which he received us, and greeting each in turn in a friendly manner conducted Colonel Gordon to the chair on the right of his own, the rest of us finding seats on either side. A brief conversation followed on general topics, and then turned on the subject of our journey.

Our host warned us of the difficulties of the country on the northern frontier of his territory, and said that, though he had no personal knowledge of its character, the reports of his officials described it as an inhospitable desert waste on which the traveller, however, well provided with creature comforts, was liable to suffer from the extremity of cold and the difficulty of respiration. He added, complimenting us on the enterprising character of our nation, that we would doubtless overcome such obstacles; and so far as he was concerned, the country he ruled being our own, and his interests identical with ours, we had his best wishes for a prosperous journey and safe return. In proof of which, he concluded, he had issued orders for every assistance to be rendered to our party in all parts of the country under his rule.

On rising to take leave His Highness conducted Colonel Gordon to the door, and there, as on arrival, shaking hands all round, dismissed us.

In the evening (August 6), Colonel Gordon, Captain Chapman, and I proceeded to return the visit of Diwan Kirpa Ram, under the conduct of Pandit Hira Nand, who came up from the Fort in a government parinda to do the honours of the ceremony. The Diwan received us in his official residence, adjoining the palace, with every mark of attention, and expressed himself highly gratified at the honour we had conferred on him. He displayed an earnestness to please us, and do all in his power to make smooth the difficulties of our route; and assured us, that by the Maharaja’s orders, he had issued minute instructions to all the frontier officials as to the supply of provisions, with strict injunctions that they were to spare no efforts to ensure our comfort and safety on the march through their respective charges. On taking leave he expressed his hope that we would find the arrangements made for the furtherance of our journey such as would meet our approval.

The day had been a thoroughly wet one, and the clouds only began to break and clear away to the mountain tops as we set out for our visit. The river was hardly affected by this rainfall at the time of our return to camp, but during the night it rose in flood and inundated the Chinar Bagh to a depth of eight feet. This is a handsome plantation of very fine plane trees on the bank of the Tsunt Kul or Apple Tree Canal, which leads from the river to the sluice gates of the Dall lake, and from its proximity to the city was at first thought of as the most convenient site for our camp. Other considerations, however, on the score of health and discipline, decided in favour of the more distant and less humid spot, and we very fortunately escaped the inconveniences of a midnight stampede amidst the marsh and mire of that tempting spot.

On the following evening we were entertained at a banquet, as the guests of the Maharaja, in the Ranbir Bagh. It is a palace, or hall of entertainment, which stands on a high masonry plinth, and forms a square block with open verandahs all round; and is covered with one of those airy roofs which, in the manner peculiar to this country, slope up from all sides to a central point, there to be topped by another of miniature proportions. It has been recently built in the Kashmir style of architecture, and occupies a prominent isolated position on the river bank above the city, and opposite the quarters allotted for the residence of European visitors, and is furnished in the Indo-European fashion. In front of it, and on either side, is a fine turf promenade supported against the river by a masonry embankment which is ascended from the stream by a substantial flight of stone steps. And in the rear, beyond a high bank of turf, is a spacious garden laid out, after our fashion, with fruit trees, ornamental shrubs, and flowering plants.

On this occasion, a company of infantry, and a military band were drawn up on the embankment from the landing steps to the verandah in which the Maharaja received his guests. Here, as throughout the building, the floor was carpeted with sheeting of snow-white calico, which answered well to counteract the dull reflection from the walls highly embellished with the minute patterns of the Kashmir style of decoration. We found His Highness and his two youngest sons pretty and intelligent children seated at the upper part of the hall with the Resident and some officers who were visitors in the valley, and his court officers standing in attendance behind him. So approaching to pay our respects, we found seats on the chairs reserved for us on either side to witness the natch which was to beguile the half-hour before dinner the grace allowed the unpunctual ones to join the feast.

A troupe of twelve or fourteen dancing girls the celebrated beauties of Kashmir attended by their torch-bearers, now made their appearance at the top of the

verandah steps, and with one accord saluting the Maharaja, quietly seated themselves in a semicircle opposite to us on the floor at the lower end of the hall. From this they rose two and two in turn, and reciting and singing and dancing, slowly worked their way up to where our host was seated; then saluting, they retired, as gracefully as they had advanced, to make way for the next pair, and so on. I will not attempt to describe this, by us much abused, performance, for want of appropriate words; because the terms “reciting and singing and dancing,” which, in default of better, I have used above, do not convey to our ideas a true representation of what they are meant to explain.

Whatever the faults of each, and, however, unsuited to our tastes, these accomplishments are none the less appreciated by those amongst whom they flourish, and by whom they are exhibited for our entertainment. Besides, apart from the divergence of taste in these respects, the performance, judged on its own merits, is not altogether unworthy of commendation; particularly if set in comparison with the spectacles presented so often on our own stage where the ballet is in vogue.

With the bayadere of Kashmir there is no studied indelicacy of dress, any more than there is abandon in the graceful movements of her limbs. These (the graceful movements) are only acquired by long practice and careful training, and to be judged fairly must be viewed with an unprejudiced eye. For the dance of the Kashmir bayadere as she sails over the floor with those graceful evolutions of the arms and body which attract the eye more than that almost imperceptible movement of the feet only recognised by the jingling of the ankle bells is quite a different sight from the fling one sees on the stage, or the performances we go through in the ballroom; though each may be appropriate in its own sphere.

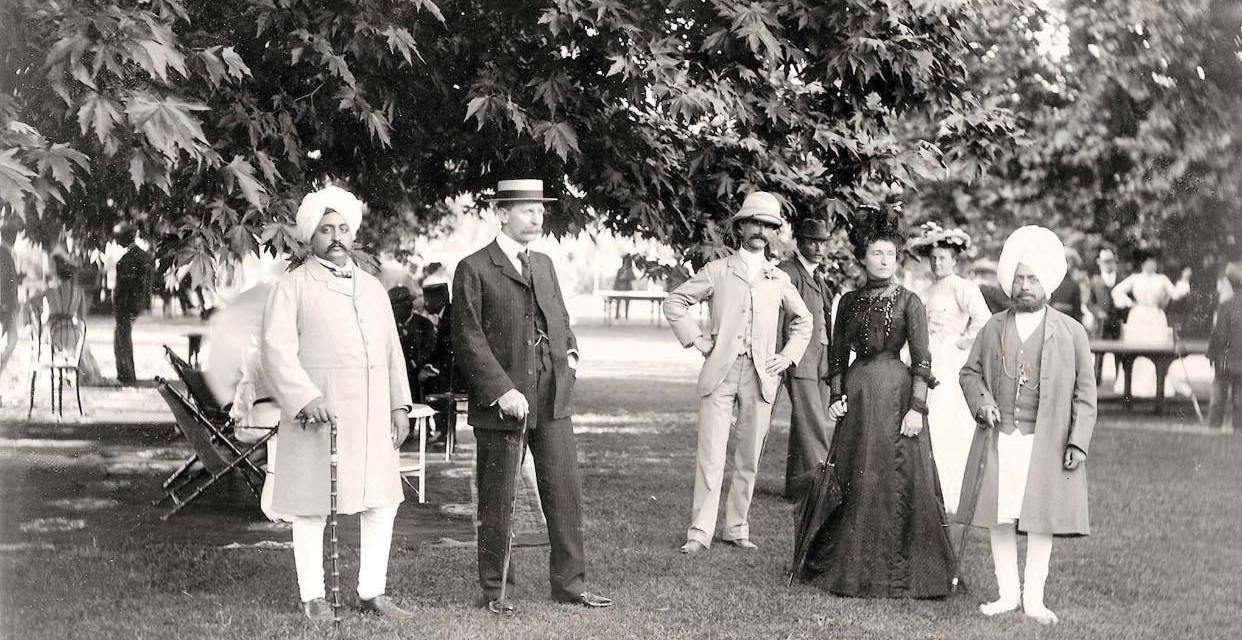

After two or three rounds had been gone through dinner was announced, and the Maharaja rising conducted the Resident and Colonel Gordon by either hand to the table, and then retired through a side door to join Mirza Fazlullah Khan, the Persian Consul General of Bombay, who, happening to be on a tour in the valley, was one of his guests; whilst the rest of us, following the first lead, ranged ourselves on either side of the board, and in the absence of our host did free justice to the good things provided.

The dinner was served entirely after our own fashion, excepting only the absence of our host from the head of his own table, in deference to an absurd prejudice the natives of India obstinately adhere to. This unjustifiable refusal to eat with us is the great stumbling-block in the way of that social intercourse which we strive to cultivate with our native fellow-subjects, and will never be removed until the native princes send their sons to be educated in English colleges, where they may learn how to associate with us on equal terms.

As it was, the Resident presided, and at the proper time rose to propose the usual toasts The Queen and The Viceroy. Each in turn was duly responded to, and then Colonel Gordon proposed The Maharaja, which was received in like manner, all standing. As each toast was drunk, the band, which had been treating us to a variety of music during the meal, struck up God save the Queen. On the conclusion of the last repetition his Highness acknowledged the compliment in set form through Diwan Kirpa Ram, and then the company rejoined the party in the verandah, where the natch was continued.

In the midst of its performance was heard the squeak of a bagpipe, to the no small astonishment of those who were not in the secret of his coming; and following it appeared our camp sergeant and piper stepping it gaily up the hall to where we were seated. He saluted the Maharaja, and then by his request gave us a performance. His appearance was splendid and, as in its handsome garb his well set-up form paced solidly up and down the hall, we could not but proudly admire all he represented.

His presence in such a scene was, nevertheless, totally out of place, and even more absurd than our dining without our host; for it sadly discomfited the fair Kashmiris, whose countenances, instead of curious glances of admiration, depicted only the disgust with which the intrusion filled their hearts. Even the Maharaja, with all his determination to please, could not divest his features of the gloom our friend’s Gaelic airs had cast upon them, and signalised his pleasure at their cessation, I trow, more likely than out of compliment to us, by ordering a handsome shawl and a purse of gold to be given to the performer.

On our return journey from this entertainment we found the sluice gates of the Dall closed to prevent the rising flood of waters entering; otherwise the garden plots before mentioned as covering the marshy tract between the river and the lake would have been destroyed by the inundation. We consequently walked across the embankment, and proceeded to camp in a boat which had been thoughtfully provided for us on the other side. It was nearly midnight when we reached camp, glad to have done with the passage by the water way, and escape its damp chills and heavy mephitic odours.

On the 10th we attended one of those military reviews of the Kashmir troops which the Maharaja holds weekly here, on the parade in rear of the Sher Garhi, when residing in this summer capital. We met his Highness as he issued from the gate of the fort, and, accompanying his unostentatious cavalcade, rode down the line paraded for inspection; and then, turning off to the saluting point, were provided with chairs on the platform from which he viewed the evolutions of his army.

There were about four thousand infantry, two hundred cavalry, and fifty or sixty wall pieces the size of camel guns upon the ground. The men were equipped in uniform similar to that of the Indian army, though their arms were decidedly inferior, and the men themselves evidently not selected on the merits of physical efficiency.

They were, however, on the whole, a light-limbed, active body of men, generally well set-up; and they marched with creditable regularity. Dogras and Sikhs, amongst whom were interspersed some Pathans and Hindustanis, composed the chief constituents of the force, and a battalion of Baltis, in the extraordinary bonnets and jaunty petticoats (which display below the knee the neat folds of their leg-bands) of their national garb, formed its most interesting and curious feature.

After the manoeuvres, the force marched past the platform, in front of which their bands had been massed, and took the routes to their different quarters. The

Maharaja evinced no keen interest in the spectacle, but, referring to the services his troops had shared in during the mutiny, pointed to them as but a contingent of the Indian army which held these hills as part of the British Empire for the Empress of India, and as at all times ready for the service of the state.

It was originally intended that our camp should halt here for eight or ten days to provide our men and cattle with the warm clothing requisite on the march across the passes, as well as to effect certain changes in our camp establishment, and alterations and improvements in our mule gear and tent equipage, which the march from Murree had rendered advisable. Our wants in these respects had been promptly attended to by the Kashmir officials who, for the sake of convenience and expedition for the city was five miles distant by road had established a temporary bazar under the trees in the immediate vicinity of our camp, so that the tailoring, cobbling, carpentry and smith- work, &c., required by our party, were at once executed under direct supervision in the booths and workshops that had sprung up around us; and accordingly on the 14th August I accompanied Colonel Gordon on a farewell visit to the Maharaja to thank him for his attention to our party, and acknowledge the punctuality and assiduity of his officials.

Haji Casim

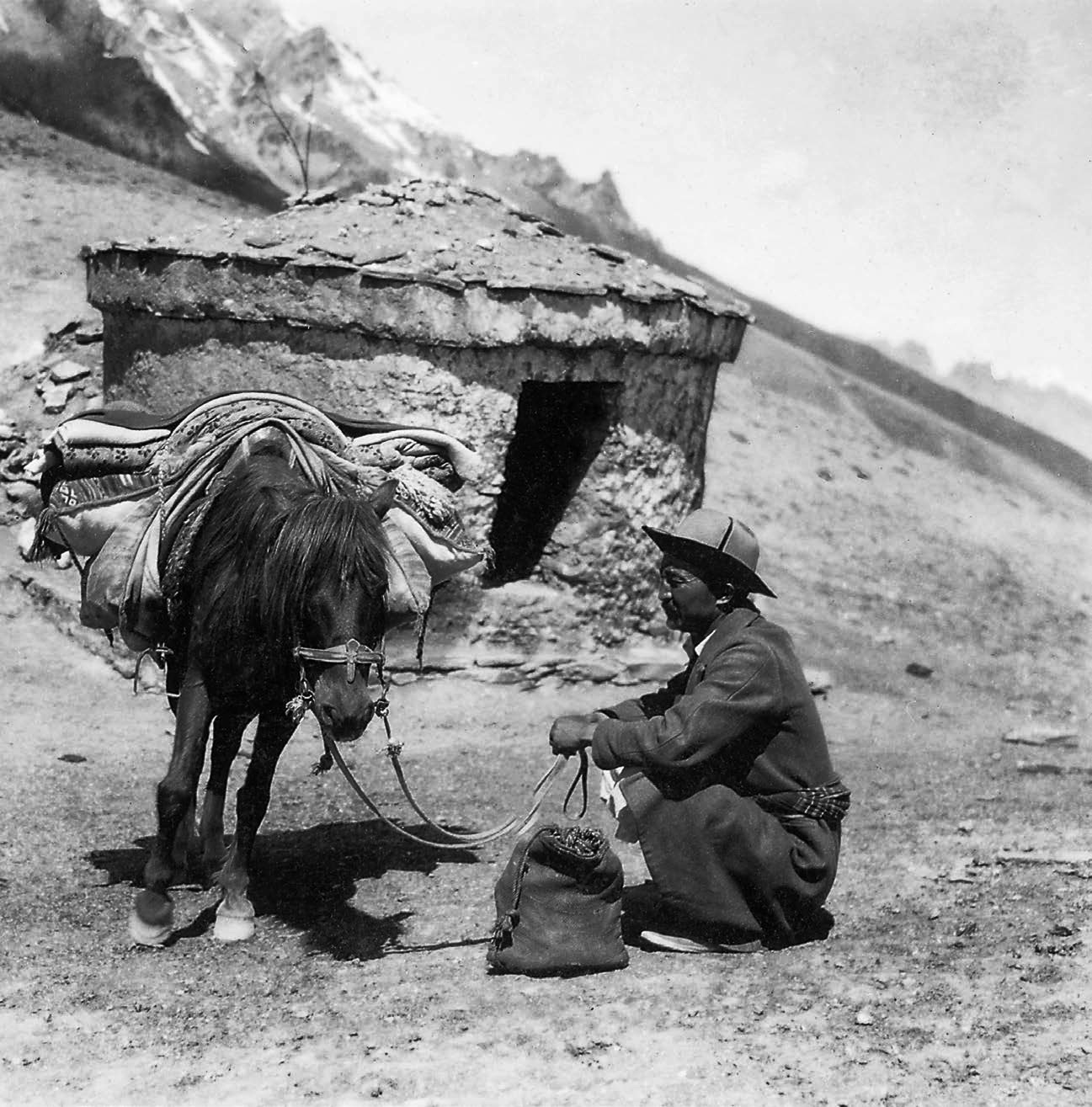

Prior to our departure from Murree I had been fortunate enough to secure as one of my personal servants a native of Yarkand who, in 1868, had left his home to make the pilgrimage to Mecca by way of India. His history was a very remarkable one, and may be taken as a type of that of many another who sets out from his remote home in Central Asia to brave the vicissitudes and dangers by land and sea of a journey of which he has no conception other than that it is somehow to carry him to that sacred spot which holds so mysterious a sway over the Muslim mind.

Haji Casim such was my hero’s name was the son of a baker who kept a shop in one of the principal thoroughfares of Yarkand city. He did a flourishing trade under the rule of the Chinese till the Tungani rebellion, filling the streets with bloodshed, violence, and plunder, necessitated his closing his business and secreting himself and family for very life in the store vaults and cellars under his tenement. The father died during these troubles, and on their subsidence, the widow with her children, emerging from their lurking, re-opened the shop. And Casim now worked the business with his mother, and was a witness of all those eventful changes which the city underwent till it was finally taken by Atalik Ghazi.

On the restoration of order, and the revival of Islam under the new rule, he took advantage of the favouring opportunity, and with some four or five other members of the family, leaving his mother to mind the shop, joined a caravan of pilgrims who were setting out for Kashmir, on the long journey they were bound, in company with a party despatched by the successful conqueror with presents for the holy shrine at Mecca.

He and his companions set out on their unconsidered wanderings with what few necessaries their humble state allowed of their collecting laden on three ponies, which also served to alleviate from time to time the fatigues of their weary march. They had, besides, a joint sum of money, hardly exceeding five pounds of our money, to meet the expenses of a journey of as many thousand miles.

By the time they reached Leh two of their three ponies had succumbed to the hardships of the road, and their carcases were left to desiccate and bleach with the thousands of others which mark the traveller’s track across those terrible Tibat highlands. Whilst the other proved such an expense in a country where money was the medium of exchange, and in a land where there was no free pasture, that he was sold to avoid threatened bankruptcy, and, instead thereof, to increase their slender means. With their small stock of money thus nearly-

doubled, the party made their way to Srinaggar, and thence through the Panjab to Bombay, where they embarked in a native pilgrim boat with a crowd of others for one of the Arab ports.

Our Haji’s account of his adventures and losses is too long and confused, from his ignorance of the names of many of the places on the route followed, for profitable insertion here. Let it suffice for us to know that he did get to Mecca, and piously performed the prescribed rites there; that he somehow found himself in Constantinople, and somehow returned thence to Lahore, a veritable pilgrim, a lonely, friendless stranger. His aunt had died in one place, her daughter had disappeared at another, his brother was lost somewhere else, and finally he and his cousin, of about his own age, lost sight of each other in the maze of some great Indian city, and neither knows the other’s fate, or did not up to July last year.

The troubles and perplexities of this doomed little band appear to have commenced at Leh, and tracked their steps in all their perilous wanderings. In one place they were cheated of their money by knaves, in another they were fed by the charity of the pious, and more often they earned their living and worked their way by odd jobs here and there.

From Lahore Haji Casim found his way to Leh as a mule-driver in the train of a Panjabi merchant; and, arrived here, he was stopped short at the threshold of his own home by a singular accident. He fell ill by exposure on the march, and applied for relief at the Charitable Dispensary established here by the British

Government in connection with the office of the Joint Commissioner. The Hospital assistant, Khuda Bakhsh, took an interest in the forlorn stranger, and after his recovery provided for him as a domestic servant in his own family.

Khuda Bakhsh subsequently abandoned the profession for more profitable employment in the Commissariat Department, and hearing of my want, obligingly placed the Haji at my service with the view to his visiting his home.

During our stay at Srinaggar, with the aid of my books, I found him a very useful assistant in picking up some acquaintance with the language of his country; whilst, in Kasghar, his services were freely in requisition by most of us. His sudden rise to such prosperity and importance led him into some extravagancies not the least of them marrying a wife and treating her friends to a succession of feasts. But this may be passed as excusable; since he considered it his duty to maintain the dignity of his position as a servant in the Embassy, and in no way detracts from his merits as an intelligent and trustworthy guide. He accompanied me back to Srinaggar, and there meeting Mr Shaw’s party going up to Kashghar, he resigned my service to return with his camp to the bride he had left behind him.

(The passages were excerpted from Kashmir And Kashghar – A Narrative of The Journey of The Embassy To Kashghar In 1873-74 by H W Bellew published by Trubner & Co in 1875. Read the first part here)