A series of developments took place before and after the crucial three days between October 23 and 27, 1947, but were deliberately not mentioned by various post-partition narratives on Kashmir, writes M J Aslam

On October 23, 1947, Pathans from North Western Frontier Province (NWFP) and its neighbouring belts reached Baramulla in Kashmir. Four days later, Indian Army landed in Kashmir on October 27. In between the two dates, and before and after Pathan entry into Kashmir, various developments had taken place.

Firstly, the role of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and National Conference (NC) in the chain of the events is most conspicuous. He was serving three years’ imprisonment on sedition charges since May 1946. He was released from the prison on September 29, 1947. His abrupt release from jail “was no princely whim on the part of the Maharaja.” (See Danger in Kashmir (1954) by Josef Korbel, page 70) but was pre-planned by Nehru who had secured his premature freedom from prison for a “job-role”.

“That the Maharaja should make friends with the NC so that there might be this popular support against Pakistan,” Nehru wrote to Sardar Patel on September 27, 1947. “Indeed, it seems to me that there is no other course open to the Maharaja but this: to release Sheikh Abdullah and the NC leaders, to make a friendly approach to them, seek their co-operation and make them feel that this is really meant, and then to declare adhesion to the Indian Union. Once the State accedes to India, it will become very difficult for Pakistan to invade it officially or unofficially without coming into conflict with the Indian Union”. (See Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, Vol. 4, p 264) Few days after the release of Sheikh, other NC leaders were also set free from jail by the Maharaja; but nothing was done to free Choudhary Ghulam Abbas and his Muslim Conference colleagues at that time. (See Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy ( 1991) by Alaster Lamb, p 130; also M M Isaaq, Nida e Haq (2014) p 177) This was despite the fact that that unlike Sheikh, who was convicted for sedation, they had not been convicted of serious charges. (See Danger in Kashmir (1954) by Josef Korbel, p 70; Lord Birdwood, Two Nations & Kashmir (1956) p 62)

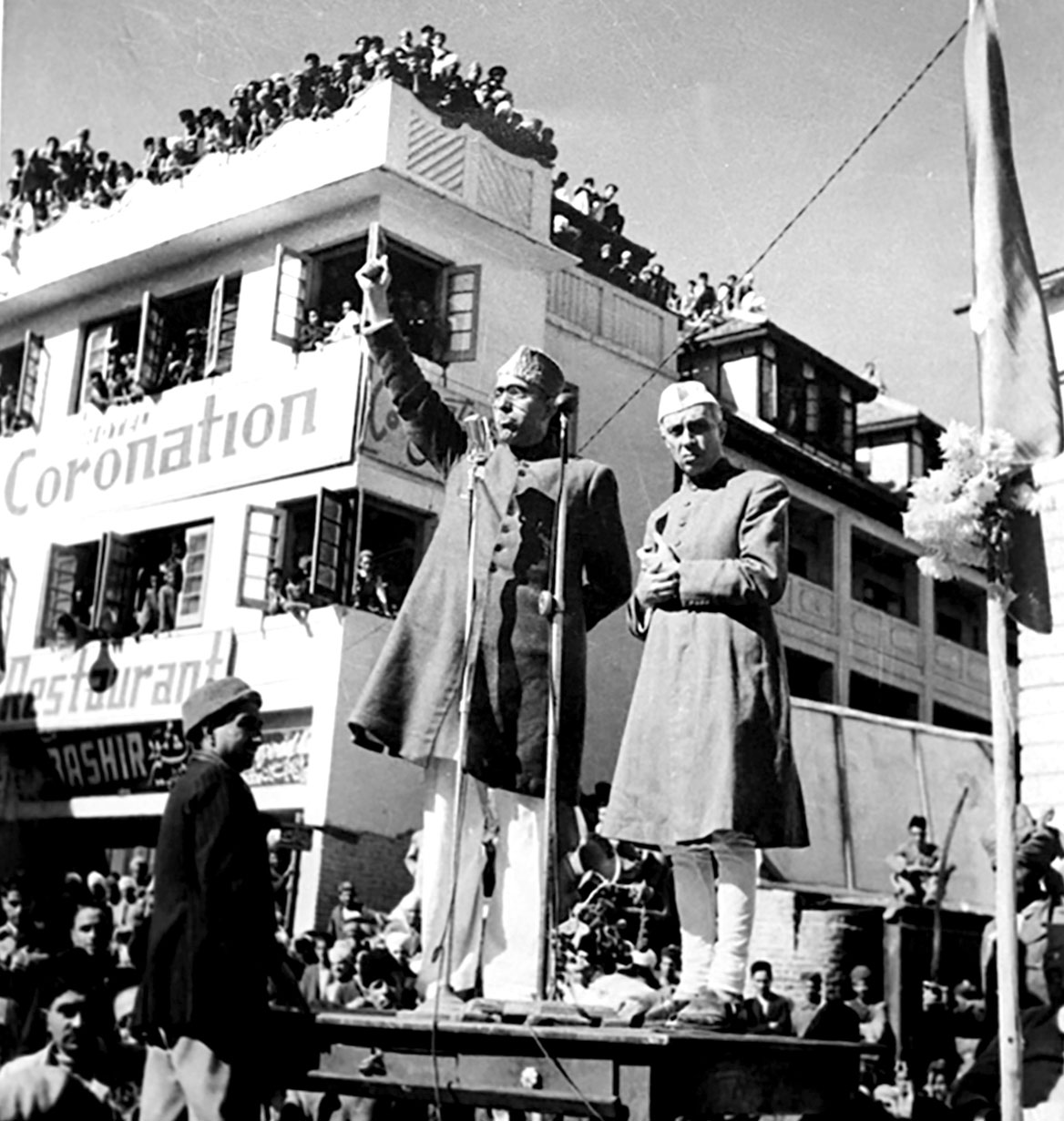

Releasing Sheikh and his followers helped to “bring about the accession of Kashmir to the Indian union”. (See Ramachandra Guha, India after Gandhi (2007) p 63) His release was the price of the accession which was to follow. (See Lord Birdwood, Two Nations & Kashmir (1956) p61) These arguments are buttressed by the well-documented facts that immediately after his release, Sheikh Abdullah set up a number of meetings and declared on October 5, 1947 before a gathering of one lakh people at Hazuri Bagh (now Iqbal Park) Srinagar that “I don’t know why I was arrested nor do I know why I’ve been released. We want first “freedom” and then only we can think of “accession”. If we have to decide about our accession, we will have to keep in mind Indian baniyas who constitute a market for our Kashmir art and craft, on the one hand, and Pakistani tangewalas on the other hand. We shall be cut to pieces before we allow an alliance between JK and Pakistan….” (see Ibid at p 62; M M Isaaq, Nida e Haq (2014) p 176)

It may be noticed here that hundreds of Kashmiri-Muslim-families who had settled years before in parts of East Punjab were returning home (Kashmir) the same time as they had escaped death, had lost all their belongings to the rioting and reached home half-naked and in tears. (See M Y Saraf, Kashmiris-Fight for Freedom ( 2009) Vol-II, p799) Since the basic pattern for accession by the princely states to India or Pakistan was being decided exclusively on a communal basis, there can be no doubt that the sense of Sheikh Abdullah’s statement was decidedly pro-Indian and anti-Pakistan. Sheikh’s subsequent actions are likewise significant. (Ibid, Danger in Kashmir p 71)

After his release, Sheikh went to Delhi where he reaffirmed his policy of joining against Pakistan and confirmed that the Poonchis were in open revolt against the ruler, Maharaja, so he supported the Maharaja, too. (Ibid, p71-72) In this scenario of the events that were shaping up in Kashmir, it has been stated that “the Kashmiris had themselves instigated the Kashmir dispute and not others”. (See Christopher Snedden‘s Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris (London, 2015), p 3) More so, because of local NC plus Delhi propaganda as there was no way to counter it then as NC dominated the entire political landscape of Kashmir then and there was virtually any mass media or effective political opposition in Kashmir. The dissent was crushed in Kashmir. The Maharaja was steadily losing control over large parts of his State (in Poonch areas, Rawalkote) and to deal with the urgency, he had to have the support of Sheikh Abdullah and his followers.

By the time of M C Mahajan’s appointment as Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir came, the Maharaja through his Deputy Prime Minister, RL Batra, was already engaged in negotiations with Sheikh Abdullah, then still in prison (but under much improved conditions) on the kind of terms which might secure his freedom in exchange for his collaboration with the Maharaja’s Government over the accession question. (See Alaistar Lamb, Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy (1991), p 129-130) There is a report that Nehru through “red shirts” (Congress-workers of Sarhadi Gandhi of NWFP) knew in advance about the possible tribal raid, and that as Nehru had informed Sheikh Abdullah in advance about this, Sheikh had taken his family members out of Kashmir and left them at Indore with a relative on October 14. (See Greater Kashmir October 26, 2016)

A number of Muslim delegations from Pakistan visited Sheikh Abdullah at his Soura residence during those fateful three weeks of October 1947, immediately after his release from prison on September 29, 1947; “All (deputations) with one demand that he must support State’s accession with Pakistan”. The delegates included eminent personalities, namely, Dr Mohammad Din Taseer, (a former Principal of SP College, Srinagar), Khawaja Abdul Rahim (Deputy Commissioner, Rawalpindi), both of Kashmir descent and also Malik Taj ud Din and Mian Iftikhar ud Din, who sought his support for accession with Pakistan, with “tearful eyes” and “some of whom even broke down under the weight of emotions while beseeching him not to accede to differently”. (See M Isaaq Munshi , Nid e Haq (2014), p181-182; M Y Saraf, Kashmiris-Fight for Freedom (2009) Vol-II, p799- 800; Betrayal Yesterday, Distortion Today, Munshi Ghulam Hassan, IAS, ex-Chairman J&K Bank)

They remained in Srinagar for two to three days and they did their best to persuade him to see the writing on the wall in the larger interests of state’s overwhelmingly Muslim population. They invited him to visit Karachi for a meeting with Mohammad Ali Jinnah. He told the delegation that he had been invited by Jawaharlal Nehru to visit Delhi and that once his Delhi visit is completed, he would fly to Karachi to meet Jinnah. (Supra M Y Saraf, p 800)

However, he did not visit Karachi after meeting Nehru at Delhi. But before leaving for Delhi, he had sent G M Sadiq to Pakistan who returned (not to Kashmir as has been misstated by NC followers) but to Delhi directly with a letter from Jinnah addressed to Sheikh Abdullah requesting his support for accession with his country and assuring him that accession with that country would be limited to defence, foreign affairs and communication only. Besides, the letter said, the Jammu and Kashmir state would be having autonomy, right to secede and permanent representation in the foreign office of that country. This letter was handed over to Nehru by GM Sadiq at the behest of Sheikh Abdullah. (Supra Munshi Ghulam Hassan) Sheikh Abdullah has, however, very poorly justified his decision of not going to that country by saying that G M Sadiq had escaped from that country with “great difficulty” and that “it was disclosed later that they had a sinister design in inviting me”. They wanted to force me, “declare accession” with them and in case “if I refuted, then they would shift me to some unknown place and announce that Sheikh Sahab had acceded to Pakistan”. (See Blazing Chinar, page 285) Sheikh Abdullah based his allegations, not supported by any independent source till date, on a report of R K Reddy who was editor Kashmir Time but initially anti-Dogra and pro-Pakistan as he was extended for his policies, immediately after partition by the Dogra regime, to Pakistan where he was associated with Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), Pakistan’s official news agency. Later, in 1948, Reddy was interned by Pakistan on charges of spying for India. Thereafter, he was reporting for the Blitz and The Hindu. Nowhere, as editor of Kashmir Times has R K Reddy, as claimed by Sheikh Abdullah ever made such an accusation. Maybe after he was extended from Pakistan as a spy, he had made such assertions.

Secondly, Sikh ruler of Patiala had already met Maharaja Hari Singh in his palace at Srinagar in the last week of July 1947. He had already acceded to India. His Patiala State Troops had already, therefore, become part of Indian Army and were already stationed in Srinagar since, at least, October 17, 1947. Patiala troops were already garrisoned in Jammu, even before that. Without the complicity of all concerned parties, the stationing of Patiala State Troops in Jammu and Srinagar was simply impossible. (Alaistar Lamb, Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy (1991), p 131; see also Telegraphic Past in Kashmir Life dated July 22, 2013)

Thirdly, we shall have to dispassionately glance through pages of history to uncover certain facts intimately associated with Pathans’ invasion on October 23, 1947. Over the years, all these established facts have been intentionally suppressed. In the months of August-September, armed gangs of Hindus and Sikhs rioters who had started pouring in three predominant Hindu districts of Jammu after fleeing from NWFP and West Punjab following Partition had started large-scale atrocities on the local Muslim population in collaboration with Dogra Army. (See A M Mattu, Kashmir Issue, Historical Perspective (2002) p48-53) By August 15, there were many meetings and demonstrations in Poonch (95 % Muslim) in favour of Kashmir joining Pakistani dominion. Martial law was introduced and meetings were fired upon under the orders of the Maharaja. Then, the whole district except for Poonch city itself was in rebel hands who were ex-servicemen of Anglo-British Army. (See Josef Korbel, Danger in Kashmir (1954) p 68; The Statesman (Calcutta), February 4, 1948) As the Muslims fell to “the bullets and swords of Hindus and Sikhs [rioters], in tribal areas, the Pathans called for a holy war of revenge against their bothers’ killers”. (See Ibid, p72)

Evidence showed that Dogra forces were “combing out all those who are known to be supporters of Kashmir’s accession to the Pakistan dominion”. There were “innumerable instances of looting of the houses of political workers. In Baramulla and Rampur, several people were shot dead on the mere suspicion that they were welcoming the “armies of liberation” (tribesmen). (See Ibid p 73) On the basis of recorded versions of several foreign authors and historians, it has been held that tribal invasion was a natural reaction of the Pathans against Dogra and Sikh atrocities on Muslims of Jammu and Kashmir and that it was not possible for Pakistani authorities even to stop them, keeping in view their centuries-old traditions of helping their coreligionists against any non-Muslim oppression. (See Shabnum Qayoom, Comprehensive History of Kashmir (2014), Vol-III, p 170; Josef Korbel, Danger in Kashmir (1954), p73-75)

On July 13, 1953, at Mazar e Shudah, Srinagar, Sheikh Abdullah said: “all the stories of killings and looting that were spread and narrated [by NC cabals] among the Kashmir masses have on an investigation been found totally baseless and unfounded”. (See Supra Shabnum Qayoom, P176) “Don’t use cuss words against them because they (Pathans) were angels we had maligned them under compulsive situation”. Sheikh Abdullah confessed before a well known Kashmiri poet Mehjoor in Jammu who later conveyed it to the publishers of Shabnum Qayoom’s said book. Ibid

These admissions of Sheikh Abdullah himself leave hardly any scope for further discussing what NC and its cadres have had maintained over decades against the tribal invasion of October 23, 1947. It simply casts thick dark clouds of doubt on all narratives of NC and Indian writers about the whole episode.

One of the related narratives is that of blowing up of Mohra hydroelectricity power station in Uri by “tribal invaders” that plunged entire Srinagar city in darkness for some time. (See Sheikh Abdullah’s Blazing Chinar (2016) p287) Actually, on October 24, 1947, the staff of the hydroelectric power station had abandoned their posts on hearing Dogra troops were retreating whom they mistook as raiders. For a while, the lights of Srinagar went out, an event which has produced its own mythology. It was blown out of proportions by the NC cadres. Some Indian writers have described in obsessive detail the way in which the “tribal raiders” systematically destroyed equipment at the power station. (See Alaistar Lamb, Birth of a Tragedy (1994) p83) “This was the work of demolition experts and not mere tribals.” (See Rajesh Kadian‘s Kashmir Tangle. Issues and Options, (1992 Delhi), p 821)

Sheikh Abdullah has levelled severest charges of killings in Baramulla town by “raiders” which are partially correct. (See Blazing Chinar p 287-288) By the time, news of the tribal attack reached to the town writes Alaistar Lamb, the town was deserted. He says that “in a pre-crisis population of 14,000, to say 13, 000 were killed is nonsense”. (See Alaistar Lamb, Birth of a Tragedy (1994) p 115) exposing exaggerated figures of V P Menon. India’s publicists have given the loss such dimensions that the word exaggeration is too insignificant to convey the truth. (See Justice M Y Saraf, in Vol-II, p941), Victoria Schofield writes there were five killings in total at Saint Joseph’s Franciscan Convent Baramulla which included three Europeans and one nun. (See Kashmir in Conflict (2003) by Victoria Schofield, p59-60) Blazing Chinar says 14 nuns were raped by tribesmen at Saint Joseph’s Convent but it is not mentioned or confirmed by any independent source of history. Ian Stephens describes murders at Saint Joseph’s Convent as “bad but secondary episode, soon inflated out of all proportion by Indian propaganda at countries of Christian West”. (See Kashmir in Conflict (2003) by Victoria Schofield, p60)

Historically and factually, it is correct that tribal invasion involved ‘dramatic but over-notorious happenings’, small in comparison with events in Poonch and Jammu. Cited in a paper titled Telling Stories and making myth by Andrew Whitehead, Prem Nath Bazaz is of the opinion that tribesmen wanted to liberate Kashmir from the tyranny of the Maharaja and the nationalist renegades. Some members of the Indian army did not resort to less killing and molestations. (See P N Bazaz’s Azad Kashmir, (Lahore) p 33 cited in Kashmir in Conflict (2003) by Victoria Schofield, p 60) The basic cause was the action of the Hindu ruler in suppressing popular sentiment and agitation for it. (See Kashmir in Conflict (2003) by Victoria Schofield, p 60 quoting Commonwealth Relations Officer)

M Y Saraf, a native resident of Baramulla gives an honest account of several “incidents of excesses” that were caused by the tribesmen against the residents of the town that included “all communities”. However, he hastened to add that bad news travels fast; the news of these incidents reached Srinagar and lent strength to the campaign of untruths and half-truths that NC leadership and the Mahajan administration had let loose against the tribesmen. (See M Y Saraf, Kashmiris-Fight for Freedom (2009) Vol-II, P 906-909, 941-942) The number of Hindus and Pandits killed did not exceed six. However, many unfortunate Sikh killings by tribesmen, albeit the majority of their families had fled from the area, did take place. An “unconfirmed” report suggests that some “red shirts” accompanying the tribesmen did the acts of killing and loot. (See Greater Kashmir, dated October 26, 2017)

(The author is an academician, story-writer and freelance-columnist. Views expressed are personal and not of the organisation the author works for.)