Kokernag’s Ashraf Dar, the key Al-Qaeda operative whom an American drone killed in Waziristan, was not Kashmir’s first global warrior. The trend took off at the peak of Communist invasion on Kabul sending a major flock to fight and die in Jalalabad and Khost. Bilal Handoo discovers the characters who fought in Bosnia, Chechnya, Kabul and now, probably in Syria

Srinagar’s Basant Bagh was bustling when a ninth-standard student left home in one fine summer day of 1986 for Jihad in deadly terrains of Afghanistan. Elections were still a year away from rigging and guns were still two years away from rattling. But the boy deeply influenced by Iqbal’s poetry followed his own roadmap to the ‘holy war’.

Ashiq Hassan Khan chose the day when Kashmiris from both parts had thronged to Peer Mitha Shrine nestled on Line of Control in Leepa Valley to celebrate the 8-day annual Urs. Before leaving home, he had done his homework well. He knew during the Urs week, the borders become porous and security softens.

After trekking miles when he finally reached the shrine, he lost his ‘Kabul compass’. For three days, devotees would see him sitting distraught in the shrine lawn. Amid his moment of anguish, he would watch Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs turning up in hordes to offer a pinch of sugar at Peer Mitha shrine as customary token of their faith.

It was then a son of Ali Mohammad Jinnah’s erstwhile driver saw him. Learning that the boy has lost his way, he took him home. That man was Mukhtyar Ahmad, whose father Khawaja Abdul Ganaie from Srinagar’s Zaina Kadal had fled to Pakistan in 1947, settled in Muzaffarabad’s Garhi Dupatta and eventually rose to become Jinnah’s driver.

The family treated Ashiq well, enrolled him in a local school and dreamed to marry him off one day with their granddaughter. But the Jihad in Pakistan’s ‘strategic depth’ was making boy restless. It seemed as if Kabul was calling everybody in.

Back home, Ashiq’s family was clueless about his whereabouts. He had left in a huff without giving anyone a whiff about his intentions. The same fact was driving his family mad. A year passed in this agony before a postman knocked at their door and handed over a letter to them with a ‘different’ stamp.

“Assalamualaikum…” the letter read, “I pray to Allah for your akhirah… Keep worship Allah… Inshallah, I will meet you hereafter…”

Khans’ were stunned to read these lines from their barely 15-year-old son. Then his father, Ghulam Hassan Khan, a driver, realised that his elder son had abandoned home for fighting the USSR, where he unknowingly rubbed shoulders with Kathwari’s son.

The destiny of Kashmiri-born American furniture tycoon, Farooq Kathwari took a radical shift when his 19-year-old son decided to walk into Afghanistan’s war-turf to participate in American-sponsored Afghan-Soviet war.

But before joining the war, Irfan Kathwari was ‘normal’. His father from a privileged Kashmiri family was living an ‘American dream’. He had made it big in US after attending New York University, working on Wall Street and making a fortune as an America’s successful furniture group, Ethan Allen Interiors Inc. He rose to become one of the most successful Muslim businessmen in America and one of its best 50 CEO’s.

His son, however, belonged to a different cult. Irfan’s pals saw him swiftly transforming from a long haired, funky boy who loved to drive his papa’s BMW to a traditional Muslim in Afghanistan, reaffirming his “love for Allah”. He took leave from Harvard Medical School to join the Mujahideen in Kabul. The question everybody sought answers for, was: What motivated the son of one of America’s wealthiest business tycoons to become a Muhajid?

Perhaps his uncle, Rafiq Khatwari – a scribe, poet and lensman, was the only person who could clear the smokescreen.

Rafiq is on records to claim that his family had a longstanding tradition of activism in Kashmir. After returning to Srinagar from Muzaffarabad in 1960, where they had stuck in 1947, Rafiq says, he and Irfan’s father were jailed for several months for student activism. “That was the family tradition that influenced my nephew Irfan.”

By nineties, Rafiq saw Irfan spending most of his time at a mosque in America. Then, Iraq had invaded Kuwait, and soon Uncle Sam dropped smart bombs over Baghdad. During that period, Irfan enrolled himself at King Faisal University in Islamabad. A few weeks later, Rafiq remembers, Irfan wrote that he and his new classmates had crossed the Pakistan-Afghanistan border in a Toyota pick up several times without being stopped.

Later, a photo portrays Irfan wearing long shirt, kameez, loose pants, shalwar. Stroking his curly beard, the photo shows him without any weapon. “Love of Allah,” he wrote in a letter to his parents, “is the only love I have ever known.” Rafiq recalls that Irfan’s mother was pruning roses under a gunmetal sky in their backyard in America, the day the call came.

“My nephew is buried in a mass grave in the desolation of Afghanistan,” Rafiq writes in a piece My Nephew the Jihad Fighter. “My brother and sister-in-law, who believe that their son was killed in a freak accident fighting the Soviets, are, of course, entitled to find solace in any idea that helps them come to terms with their sorrow.”

Like Kathwari, Khan didn’t know the fate of his son in the beginning even after receiving a few letters from him. But as his neighbourhood – Maisuma – became a hotbed of rebellion by the dawn of momentous 1989, Khan met a man from Srinagar’s Hyderpora, who eventually became his messenger.

That Jama’at-e-Islami ideologue running a local seminary in Hyderpora was the default foot-soldier of pro-Pakistan local group in mid-eighties. He would raise slogans and hoist Pakistan flags to express his protest against Indian establishment in Kashmir. Then events like Maqbool Bhat’s hanging, torching incident of Kashmiri driver by soldiers over fare demand, molestation attempt of a Yousmarg farm girl by a patrolling party and series of burning incidents believed to be the brainchild of Hindu right-wingers made the man restive.

It was then he met the two men who became one of the pioneers of gun struggle in Kashmir – Abdullah Bangroo and Maqbool Ilahi. The man they met was a steel fabric shop owner of Hyderpora, Abdul Ghaffar Bhat, who later became prominent with his nom de guerre, Hanief Hyderi.

The three of them (Bhat, Ilahi and Bangroo) floated a group that sent a word to many clerics, leaders in 1985: “Do something to counter the Jagmohan’s decree!” The newly-inducted Governor Jagmohan Malhotra had then shot a bizarre ban on livestock slaughter on eve of Janmashtmi. Qazi Nissar was the only cleric who responded. He turned up in Islamabad’s square with two lambs, slaughtered them in protest, and thus created ‘Qazi Nissar moment’.

The group later became one of the first groups to crossover to Muzaffarabad in 1988. A year later, they were getting ready to step into “Azad Kashmir” again. But before leaving, Hassan Khan, the Basant Bagh driver, told Hyderi at Maisuma, “You may meet my son there. He is staying with a Kashmiri family there in Garhi Dupatta. He left home in 1986 for Afghan Jihad. Tell him, his parents are proud of him…”

But in other Kashmir, the things weren’t the same again. With the fall of Zia regime, Benazir Bhutto, the former classmate of Rajiv Gandhi, had shut down all training camps. Then, Hyderi saw how the incoming Kashmiris were pushed back. But the five member group, comprising Bangroo, Ilahi, Ghulam A Gojri, Ayub Bangroo and Hyderi chose Afghanistan over Kashmir.

They were sent to Jalalabad, where they were greeted by famous warlord and Hezb-e-Islami chief, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and the Sher-e-Panjshir, Ahmad Shah Massoud. Hekmatyar, an engineer and a craze for Kashmiri militants, was delighted to see the first armed group from Kashmir stepping into Afghanistan. “I am happy that Kashmiris have finally picked up guns,” Hyderi heard Hekmatyar. “Let this war end, we are coming to Kashmir to fight for your rights…”

In Afghanistan, the group was taught the war strategies of legendary military commander, Saladin Ayubi – the one who conquered the Jerusalem, before sent to fight soviet army at Khost front. Hyderi shortly saw bodies flying up, raining smithereens over battlefield when stuck by soviet missiles. He saw the ground littered with human bodies and body parts. The group would gather those bits and pieces and hand over to the locals for burial.

Hyderi trained in anti-aircraft guns and rocket-propelled grenades was shortly sent in Eastern Afghanistan before an escort force for Arab militants at Jalalabad camp. Later he learned that an estimated five hundred Kashmiri militants were fighting with Mujahideen when the strategic Jalalabad was snatched from Najibullah’s control. Even J&K police has identified around 20 youth who died while fighting erstwhile Red Army before they left Afghanistan in 1989.

After six months in Afghanistan, when Hyderi returned to Muzaffarabad, another war was about to break out, thus calling thousands of Muslims across the globe, the Jihad in Bosnia.

For some Kashmiris who were in the middle of turmoil themselves, the very thought of Bosnia was unsettling. The war was part of the breakup of Yugoslavia following the Slovenian and Croatian secessions from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991.The political representatives of the Bosnian Serbs supported by the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević and the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) rejected the referendum. To wrestle territorial control, they mobilized their forces inside the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

By 1992, war spread, accompanied by the ethnic cleansing of the Bosnian Muslim and Croat population. Events like the Siege of Sarajevo and the Srebrenica Massacre later became iconic of the conflict, forcing NATO to intervene in 1995. The war didn’t end before consuming around 100,000 lives, outraging the modesty of 50,000 women (mainly Bosniak Muslims) and displacing over 2.2 million people. The grim war numbers made it the most devastating conflict in Europe since World War II.

Like myriad men then, the Bosnian war also distressed the Kashmiri poet in English language, Agha Shahid Ali. He sent his mentor James Merrill a draft of a political poem rhyming stanzas about the war, asking him to be “brutally frank” in his critique. Feeling that Ali had used too many off rhymes, Merrill told him, “While there isn’t much you can do about Bosnia, you can improve this poem.”

But what the poet couldn’t do, the pilot did.

The ‘legendary’ Kashmiri pilot Nadeem Khatib left Srinagar for Sarajevo and fought the war that had pushed Muslims to the margins.

Son of an erstwhile chief engineer of Srinagar’s Rawalpora, Nadeem educated in city’s best Christian school, Tyndal Biscoe and later graduated in geology, geography and economics. He shortly realised his childhood dream by becoming a pilot. But more than flying machines, his mind, as per his close friends, was getting drifted in Muslim world conflicts.

The best friend of JKLF’s first boss, Ashfaq Majeed Wani, Nadeem remained on the edges when militancy broke out. The transformation took place after his affluent family sent him outside the state to learn ‘flying’. But Nadeem left the commercial pilot’s training midway, returned home, and eventually left for the South East School of Aeronautics, Georgia to train as professional pilot.

That was the time when Bosnia had become a slaughter house for Muslims. “Such thoughts were badly disturbing him,” says Nadeem’s close friend. “He then went to Bosnia to participate in the war.” The prominent pro-freedom activist Shakeel Bakshi endorses the views of Nadeem’s friend. “Yes,” he says, “Nadeem did participate in Bosnian war. He was in Sarajevo and other places, fighting Serb oppression on Bosnian Muslims.” As per Bakshi, several Kashmiris did participate in the war, “but they are tight-lipped for the fear of reprisals”.

Back home, none had an idea, that Nadeem, a prominent member of the Srinagar Golf Club, has become a global jihadist. In 1995, as the Bosnian war was officially declared over, he returned home with his pilot’s licence. He shortly left for US again to complete a jet pilot’s course from an institute in Atlanta. He continued work there as a commercial pilot besides instructor before a caller from London informed his family, “He is dead!”

Later, it came to light that Nadeem had left US to join al-Badr training camp in Pakistan. He had crossed over to Kashmir where he was killed at Buthal village in Udhampur’s Gool area in a gunfight with BSF on February 21, 1999. He was 32.

After his death, his letter reached to his parents, who didn’t know Nadeem had joined militancy, “I am going at the call of Allah and doing what Allah has made our farz (duty). I am aware this might hurt, but duty to Allah comes first…” Ten days after his death, his body was exhumed by his family, brought to Srinagar, buried in Martyrs Graveyard at Eidgah.

“In US, his thoughts were inflamed after reading Syed Qutub Shaheed,” says Nadeem’s friend. “He would say that his vision has been finally cleared.”

After returning Muzaffarabad from Afghanistan, Hyderi was informed of establishment’s planning to create Hizbul Mujahideen. Then, militancy was dominated by JKLF, a nominally secular outfit. With Benazir ruling, the plan was to facilitate the rise of Hizb, affiliated to Jamaat-e-Islami. It would decisively shift the insurgency to an Islamist, pro-Pakistan ideology. Hyderi was too inept to understand the changing equations on the ground.

But before he could step back to Kashmir, Sheikh Abdul Rehman, Amir Zila Jama’at-e-Islami Muzaffarabad told Hyderi one day, “A boy from Kashmir is here to meet you. Do talk to him in Kashmiri, he will feel at home.”

Hyderi met the boy, who turned out to be none other than the driver Hassan Khan’s son, Ashiq. The boy smilingly told him, “I just overheard your presence in the area. And that’s why I have come to meet you.” Hyderi hugged the boy and told him that his father is his good friend. “Everybody misses you back home. But tell me, how did you reach here?”

The boy narrated his whole journey – how he treaded treacherous terrains, reached the Peer Mitha Shrine, met the Kashmiri family besides his perpetual cravings for Kabul. “So, why don’t you come over and meet my new family here,” Ashiq insisted. “No, boy! Not this time. I am in a rush. Will meet you soon, Inshallah!”

In that summer of 1989, Hyderi was back in Kashmir with a group of 10 other fighters. By November that year, as ISI failed to mould JKLF into pro-Pakistan ideology, it recruited JKLF cadre to set up a new organisation, al-Badr. Abdullah Bangroo, Maqbool Illahi, Hyderi and others were part of it. The outfit was later renamed as Hizbul Mujahideen. Soon the Pattan school master, Ahsan Dar was appointed its chief, while Abdullah Bangroo alias Khalid-ul-Islam became his military advisor.

In a short span of time, Hizb’s armed cadres swelled in thousands. The outfit’s first major strike is believed to be a key political assassination. By 1991, major groups, including Tehreek-e-Jihad Islami led by Abdul Majid Dar, the Hizb negotiator with New Delhi, merged with HM. And then on November 11, 1991, Mohammad Yusuf Shah aka Syed Salahuddin took over Hizb operation, replacing Ahsan Dar. The move marked the takeover of Hizb by Jama’at-e-Islami, a relationship that the two couldn’t sustain for long.

Hyderi who remained underground and silent witness to the shift in Hizb’s rank and file decided to quit the outfit by 1993 and crossed LoC to understand the madness behind the method of divided house. But he ended up floating a new organisation, Jammu and Kashmir Refugees Welfare Association, in “Azad Kashmir” to advocate for the former militants. During his advocacy campaign, the world including a Kashmiri studying medicine in Russia was witnessing Russian aggression on Muslim-dominated Chechnya.

Zubair from South Kashmir landed in Russia when Russian President Vladimir Putin established direct rule of Chechnya in May 2000. For the politically conscious youth well-versed with world conflicts, Putin’s move appeared mere dictatorial move.

As Putin appointed Akhmad Kadyrov interim head of the pro-Moscow government in Grozny (Chechnya’s capital) and granted the Chechen Republic a significant degree of autonomy, the Chechen separatists rebelled. Shortly Kadyrov was assassinated in a bomb blast thus making his pro-Moscow son Ramzan Kadyrov Chechnya’s de facto ruler.

Not far away, in Russian city of Saint Petersberg, Zubair was taking keen interest in Guerrilla phase in Chechnya than medicine.

The centuries old Chechen-Russia conflict had escalated in 1990s after the Soviet Union disintegrated. The Chechen separatists declared independence in 1991. Three years later, the First Chechen War broke out. In 1999, the fighting restarted and concluded the next year with Russian security forces establishing control over Grozny.

By 2003, the sober son of South Kashmir’s landlord family was in the southern Chechnya, fighting against Russian military convoys along with natives. He returned home after the 2004 Beslan School Siege that saw the rebels capturing over 1,100 people as hostages. “Chechnya was always the holy war for me,” says Zubair, now a prosperous orchardist. “I came back after realising that war against the empire must not be a broken war on ideological lines. That is crisis. A decade ago, I only walked out of that crisis gripping Chechnya.”

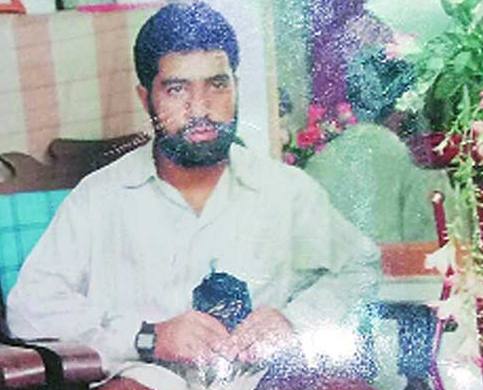

Interestingly, Kashmir’s presence in global jihad might not be on higher scale, but the footprints are glaring. In 2007, a Bandipora boy, Aijaz A Malla died in Afghanistan while fighting against America’s “war on terror”. Hailing from Bandipora’s Patushahi village, Malla vanished from his home in 2001, joined Pakistan-based Harkat ul-Mujahideen and subsequently became the first Kashmiri to participate in the Taliban-led jihad in Afghanistan. As per police records, Malla was just 11-year-old at the time. “I am again going to fight the infidels in Afghanistan,” Malla told his family days before his death, “and do not know if I will come back alive. Pray for me.”

Like Malla, the 15-year-old Muhammad Ashraf Dar of Nagam village of Islamabad’s Kokernag also left home for the global jihad in 2001. After remaining in touch with his family till 2014 winter, Ashraf alias Umar Kashmiri of al-Qaeda outfit was killed in a US drone attack on January 5, 2015.

And now when the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is becoming a new symbol of “global jihad”, it is said one Srinagar youth has “joined” it. The car-enthusiast who was pursuing masters in Business Management from Australia is the first Kashmiri to “join” IS in Syria in 2013.

Back in “Azad Kashmir”, life for Hyderi was akin to exile. He was getting restless over the turn of events. In his moment of unease, he once went to a tea shop in Garhi Dupatta with his associates. There, he saw a photograph, leaving him shocked.

In that “Shaheed” captioned photograph, he saw a known smiling face. Moments later, as his memory flashed, he blurted out, “Allah u Akbar!” That was Ashiq, the Basant Bagh boy.

To address his ‘aching’ curiosity, he asked the shopkeeper, Mukhtyar, the man who took Ashiq home from the shrine, how the boy died. After learning that the man was Hyderi, the shopkeeper hugged him, cried aloud, before telling him, “Ashiq was martyred on his third Jihad trip to Afghanistan.” Like Farooq Kathwari’s son, Ashiq too was buried in some mass grave in Kabul.

Later a letter sent by Mukhtyar broke the news to Ashiq’s family in Srinagar, “your son has attained martyrdom while fighting the holy war in Afghanistan…”

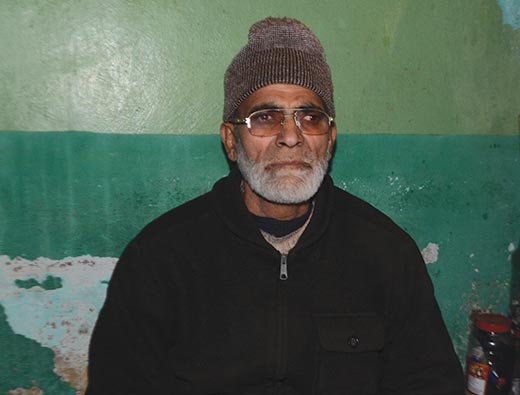

Today, as his toothless, humped and greyed father stands near his 2014 flood-ravaged house in Basant Bagh, he expresses strange longing and pride for his son. A few miles away, Hyderi who returned to Kashmir in 2006 has confined himself within four walls. He is now in the middle of what he calls a “different Jihad“. He is writing a book on his eventful past, and the “wrongs in between”.