Plague like many other epidemics got imported into Kashmir. A Mitra, Kashmir’s erstwhile Chief Medical Officer of Kashmir treated the plague-infected and tackled the epidemic for the government in 1903 while keeping a detailed record of the history.

Kashmir possesses a recorded history in Raj Tarangini of all important events which happened in the country for a long time past, but no record of any epidemic disease similar to plague is available.

The fact that one of the common abuses used by the Kashmiri is piyoi toun or “plague take you ” makes one think, however, that the people had previous experience of this dreadful disease. Nawab Mautamad Khan, one of the paymasters in Jehangir’s Army, says in Ikbal Namah that plague raged in a severe form in Kashmir.

Plague Near Kashmir

In Jammu, 155 miles from Kashmir, and with which place it is in close relationship, officially and commercially, plague has been present since 1901. In Poonch, 26 miles from the borders of Kashmir, there was plague in the autumn of 1902. Rawalpindi, which is connected with Kashmir by a road, gets plague every year.

Thus plague being in existence so near Kashmir, it was obvious that sooner or later it was highly probable that Kashmir would be visited by the disease.

Inspection of Travellers

There were arrangements for examination of travellers coming to Kashmir from Jammu and from Rawalpindi. One case, very probably of plague, coming from Rawalpindi, died near Uri, 60 miles from Srinagar, on 8th October 1903 and was cremated there.

Soon after this elaborate arrangement for disinfection of clothes by Bowman’s Disinfector were about to be made at Uri when on the 13th November a tonga with a veiled native woman and two servants passed Uri. In this tonga came the first case of plague in Kashmir. The inspectors failed to detect the disease. The order to them was to take the temperature of every traveller. Their subsequent report showed that all the occupants of the tonga at the time of inspection had normal temperature

History of the First Imported Case

On the evening of the 18th November 1903, a man was found at the gate of State Hospital in Srinagar with following symptoms: Fever, temperature 100F, anxious look, slightly wandering mind, inguinal glands of both sides swollen. He was left there by a hired pony man from Kralpura, a village six miles from Srinagar. The man said he was a servant of a Mrs B, who was camping at Kralpura.

The symptoms at once suggested plague, and the man was immediately removed in a tent away from the city in a large open ground. Mrs B, a Kashmiri woman, lived near Rawalpindi. She left that place by tonga with two servants on the 11th November. The tonga was booked in the name of Mrs B who had a Burkha (veil) on her. They reached Murree the same evening and stayed for the night in Curzon Rest House. Ghulam Mohamed was the cook and Abdul Rahman was the khidmatgar.

Next day they left Murree and passed Kohala at mid-day where they were examined at the inspection post and provided with the usual passports in which they were entered as “In good health.”

They reached Ghari at night. Ghulam Mohamed was not feeling well that night and could not cook food for his mistress. They left Ghari next morning, passed Uri at mid-day, where at the inspection post they were again examined and passed. They reached Srinagar at 10 pm, and engaged a boat. Ghulam Mohamed did his usual work that night. They were in this boat for two days.

On the 16th Mrs B left in a dandy for Kralpura, the two servants accompanying her on foot. There, they went into the house of Subhan But, a relative of Mrs B.

Ghulam Mohamed occupied a small room on the ground floor of the house. On the 16th, 17th, and 18th Ghulam Mohamed could not do his usual work and was laid up in the room. Several grain dealers and cloth merchants stopped in this house during this period. The patient Ghulam Mohamed died on the night of the 19th. This was the first imported case in Kashmir.

Measures Taken

- The body was buried in a grave 10 feet deep with 2 feet of carbolate of lime surrounding it. Only two persons helped in the burial.

- All articles which came in contact with the patient, including bedding, tents, etc, were burnt.

- There were three contacts, a hospital assistant, one khidmatgar and one sweeper. They were segregated in camp, usual measures of disinfection being taken.

- At Kralpura the house of Subhan But was burnt together with everything contained in it, also the grains kept in the compound of the house by dealers.

- Mrs B, her servants and all members of Subhan But’s house, the ponyman who brought the patient to the hospital, and all suspected contacts were segregated in camp. None developed plague.

The Second Case

About 500 yards from the tent in which the plague case was kept, a police guard of four constables was camped to prevent any communication with the plague case.

After the death of the imported case the attendants were in segregation and the police guards were on watch over them. On the morning of the 25th one of the constables was found ill with slight rise of temperature, pain in the chest, very anxious look, and spitting of blood-tinged sputum. On physical examination slight dullness and rough breathing were found. Evening temperature was 101F.

When I saw him in the evening, I found him slightly delirious, and I thought the man had pneumonia from exposure to the severe cold of November in an open field. There was no glandular enlargement. He died at night. When I heard of his death, I suspected pneumonic plague. The body was accordingly buried in a deep grave in an open ground. Some relatives of the deceased and the mullah assisted in the burial, but their application to remove the body for burial in the city near their house was refused.

How this man contracted plague is a mystery. He was supposed not to have gone near the patient at all. I have heard a story, but it is not confirmed by any eye-witness. This constable, probably with the connivance of his brother, who was the hospital attendant on the plague case, went into the tent and handled the dead body for the purpose of stealing anything which could have been found. It is further said, that he put his mouth on the finger of the deceased to bring out a ring, biting it with his teeth. If this story is correct, which I believe it to be, plague commenced in Kashmir from a crime.

On the morning of the 28th, that is, two days after the death of his brother, the police constable, the hospital attendant who was in the segregation camp, was missing. As soon as the matter was brought to my notice, I thought that the man must have got ill and absconded somewhere. In bringing this matter to the notice of the police, I asked them to take the same steps as they would take to find out the whereabouts of a murderer, and pointed out that this man, wherever he was, would probably infect the country if he was plague-stricken, which probably he was. He of course died, but where and how, we do not know.

Sudden Outbreak of Plague in Srinagar

Ten days passed without any further development of affairs. On the morning of the 11th December, we heard of several deaths in two houses in Srinagar. The following was found:

In the house of the police constable who died in camp, a man died on the 10th December, another on the 11th. There were five persons living in the house. In another part of the town, the first case occurred in the house of a relative of the police constable who himself was also a police constable and had attended the two patients in the first house, 5 deaths had already taken place within six days and three persons were found ill. They were all relatives of the police constable, his father, mother, sister, wife and children. A sister-in-law living in the next house also died. The symptoms were, pain in the chest, slight fever, 101F, serous sputum, wandering mind, staggering gait, tongue black in centre. They all died the next day.

Within a few days eight different centres of infection appeared in Srinagar, all patients being contacts and relatives of the cases in the house of the police constable who died in camp.

How the Infection Spread?

There are two probable stories, both of which may be correct, and both incidents might have occurred simultaneously.

- The dead body of the police constable, who died in camp and who was buried outside the city, was exhumed by his relatives, brought in his house and reburied there. Police constables being concerned in the matter, their comrades, who must have known of this, kept silent.

- 2. The hospital attendant who get ill in camp went to his relatives’ house in a village 17 miles from Srinagar. His relatives from Srinagar went to attend on him there and probably brought the dead body to Srinagar.

So the infection started from either the police constable or his brother, the hospital attendant.

News were received at this time of an outbreak in the village called Geru. This is either due directly to the hospital attendant or through his relatives coming to Srinagar to attend on their relatives and returning to Geru with the infection. Unfortunately no one lived to tell the true tale.

Measures Taken

These may be briefly stated as follows:

(1) Evacuation of the house where plague case was discovered. Its burning wherever possible after payment of full compensation of house and property. Where this was not possible, it was infected by perchloride of mercury, door and windows were left open, holes were made in walls and roofs, and the main door was closed up and guarded.

(2) An open place nearest to each infected centre was selected, where temporary huts were put up, in some of which actual cases were kept, and in others at a distance all contacts and inmates of the infected houses were removed. The huts were built with bricks and every possible arrangements were made for comfort, though it was obviously very difficult to do so in the December climate of Kashmir with severe frost and heavy snow. Stoves were provided. Warm clothing and bedding were given in abundance, fuel and charcoal, food, including tea and meat were also given.

Subsidiary Measures

- A careful system of registration of deaths in the city was organized and arrangements were made for the reporting of suspected cases and their inspection. As all cases were directly or indirectly connected with police constables, it was sometimes very difficult to get a report in time.

- A gang of coolies, first inoculated with Haffkine’s prophylactic, was engaged for disposal of the dead and disinfection, in which latter work they were trained.

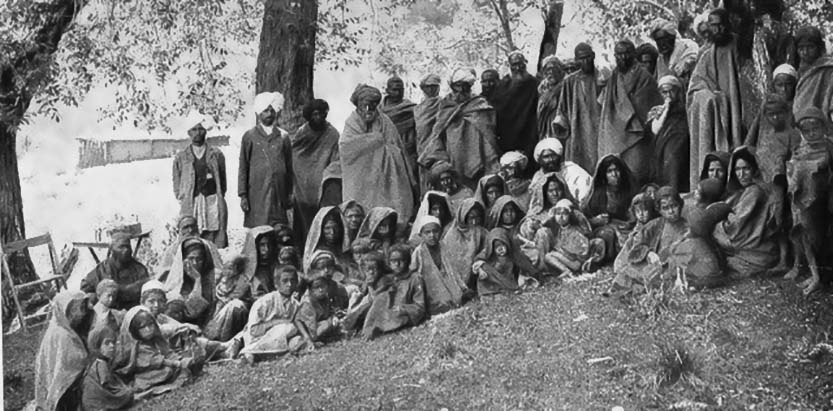

The attitude of the people

In the beginning the people in Srinagar would not believe that it was Plague which appeared in the city. Most absurd stories were circulated, and many attempts were made by misrepresentation to discredit the agencies who were lighting at great personal risk for public good. The superstition of the people was that the police constables and their relations were only suffering for their sins. Many educated people, from whom better things were expected, actually tried to rouse popular opinion against us by making false representations about discomfort in the camps and spreading the rumour that it was only pneumonia and not a pneumonic plague.

But in spite of all difficulties, the measures were strictly carried out with every possible attention to the comfort of the people who were segregated, with the result that there was no new centre of infection and no new cases anywhere in the vast, congested and insanitary town of Srinagar, except in the isolation camps or in the few infected houses till the disease died out.

In the carrying out of plague measures no help of any kind was received either from the people or their leaders. Everything was done through official agencies. No heed was paid to the clamour of the people, and measures which were thought right and suitable were carried out with a firm hand. When plague ceased in Srinagar and news of hundreds dying in the rural districts reached the city, a large deputation awaited on us begging to do something to prevent its re-introduction into the city and to repeat the measures which were previously taken, should it take place.

Districts

I have mentioned how the infection reached Geru, a village 17 miles from Srinagar. In this village the Lambardar the village headman, who was the richest man in it and had a large house with large quantity of grain stored and a number of cattle, was the first to die. His three sons died soon afterwards.

This man had relations far and wide in this and neighbouring villages, who came to sympathise with the family. From Geru, it spread to Charsu, from Charsu to Sail, and so on till it reached Tral, a very populous village 20 miles from Geru.

Our action in this district was in the beginning the same as in Srinagar. When, however, it spread over many places, the measures had to be relaxed.

Wherever possible, the sick and the contact were separated and houses were disinfected. A few houses in which the first cases occurred were burnt, others were disinfected by perchloride of mercury.

From Srinagar the infection also went to another village named Kripalpur, near Pattan, through a relative of the constable. One house was infected which was destroyed, the sick and two contacts were segregated, of which one subsequently developed plague. There was no more case here afterwards.

News came from villages in the neighbourhood of the Woolar Lake, that a large number of men suddenly died there in a few days. The police officer hinted at poisoning. It was, however, found out that plague of virulent type was raging there for over two weeks, and about 20 persons died. It was concealed by the Police Chowkidar and Lambardar, both of whom afterwards died of plague. It rapidly began to spread in the neighbouring villages.

A man came from Geru to Gund Jahangir and died there on the day of his arrival. Those who helped in the burial of the corpse next got the disease.

These villages are small islands on the Woolar Lake. They were totally submerged during the summer flood and all huts were constructed afterwards. The soil reeked with products of decomposition of small fish and water nuts, which latter is the chief food of the inhabitants. They drink very filthy water. Corpses were buried in shallow graves close to houses. In a short time these infected places became very insanitary with a peculiar offensive smell due to decomposition of organic matter. The villages suffered badly. Practically nothing could be done here as no measure was feasible. The virulence, however, gradually lessened, but the epidemic slowly continued for six months.

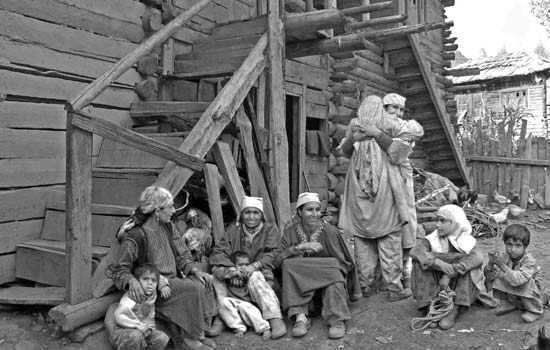

On the south of the Woolar Lake there is a large circular strip of land surrounded by water and intersected by canals. On this are several villages, many of which are flooded when water rises high, others being on higher level, are always dry. The land is very fertile, and people are much attached to their tenements. The situation is open with the vast expanse of the great and blue Woolar Lake in front with snow-clad mountains on the back ground.

Standing at this spot, it strikes one that plague probably never had a more picturesque abode. Except in few instances the houses are built in a row with a pretty good space between each. If instead of being hovels they were better built houses, one would have said that they were neatly arranged villas with vegetable gardens. The interior of the huts, however, present a different picture.

On the lower story are the cattle and poultry with one or two small windows; in the middle story the family live; in this story there is no window except one in a few huts. The upper attic is used for storing fuel, dried cow-dung, etc, in winter, and in summer for living or cooking purposes. It was easy to realize why plague, introduced into these huts, would have a luxuriant growth within them. It was a pitiable sight to see some of these villages nearly depopulated, such as Boon, which was only a few months ago, a flourishing little village with neat and well-built houses, signs of opulence of the village still existed, many houses were empty, others were occupied by distant relatives come from other parts of the valley and occupying the houses and property left without any immediate heir.

Even the Lambardar was a small boy who has just stepped into the shoes of his father, the old Lambardar who recently died of plague.

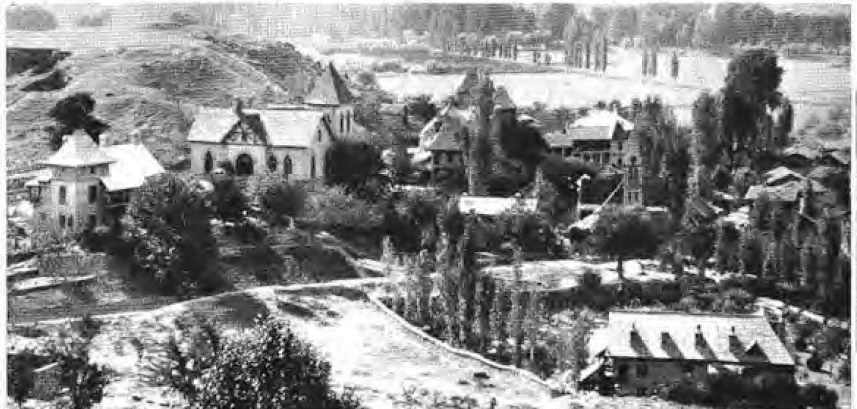

Sopur was the largest town near these villages. There was one imported case in it which was dealt with in the usual way. No more case occurred there.

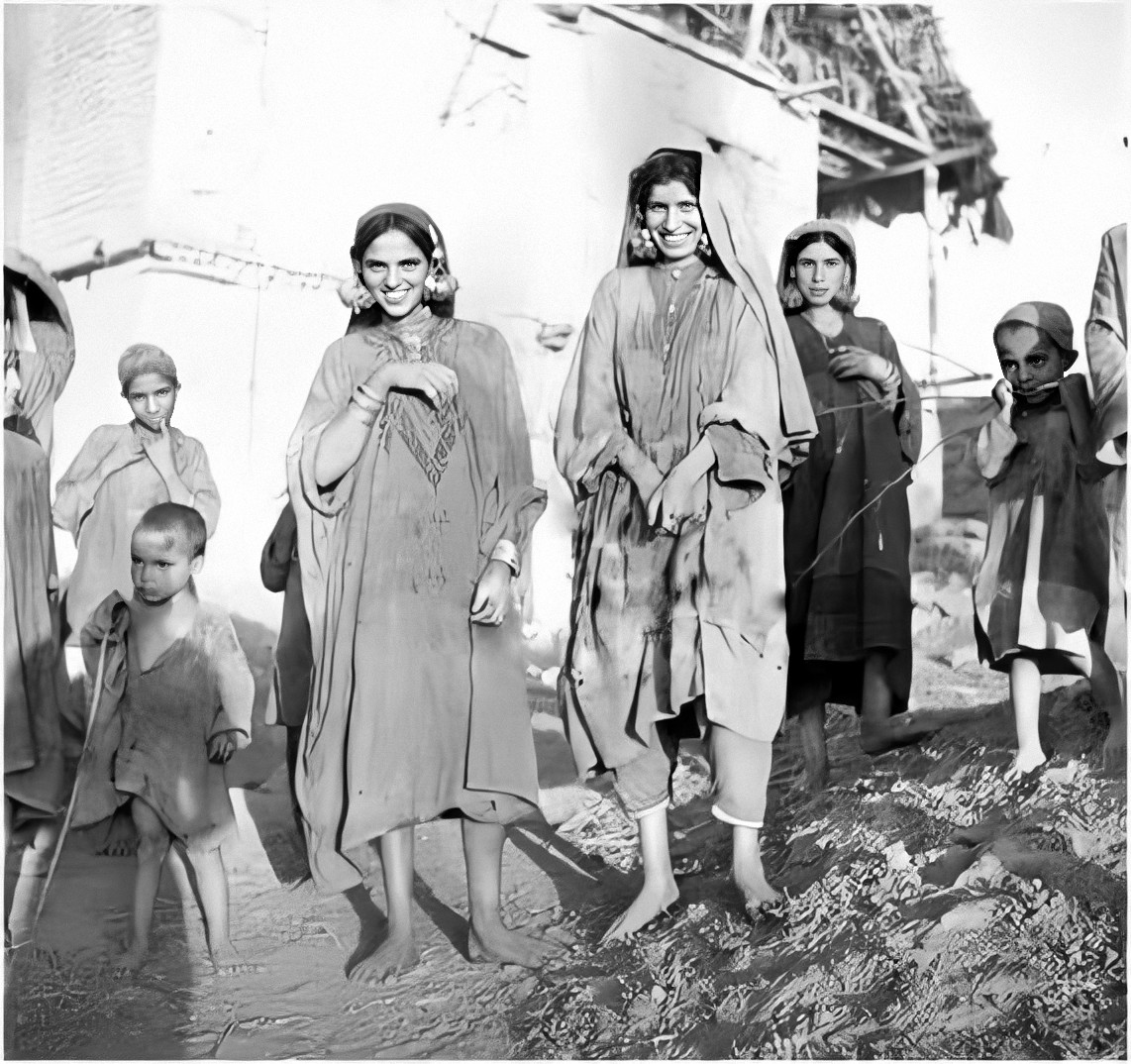

It was indeed very fortunate that the infection was not re-introduced to Srinagar from these villages from where a dozen boats with water-nuts used to come to Srinagar daily. In fact, one such boat with a plague case was detected on the river midway between Srinagar and the Woolar Lake. The conditions of life in these villages during the month of January and

February were extremely unfavourable. Everything round was frozen. A bleak wind always blew. Very little food, except water-nuts was available. All were paralysed with fear, grief, cold and inanition, and nobody took care of the sick or came forward to bury the dead.

Type

The first imported case was of bubonic type, the next infected case was pneumonic. Almost all subsequent cases were pneumonic, except a few about 45 in 1374. Many were, no doubt septicemic. It has been suggested that in winter the lungs were more susceptible to harbour the germs, owing perhaps to the presence of catarrh, bronchitis, etc, but this theory can hardly cover all grounds. It is, however, now established that under local conditions the bubonic variety may change into pneumonic, and may persistently remain so during an epidemic.

Mode of Infection

In the pneumonic cases the principal means of communications is direct infection through sputum, which is loaded with bacilli and which is sprayed about when the patient coughs or even when he speaks. In the

Kashmir epidemic this has been the sole factor in its dissemination.

Thus during the epidemic those only who came directly in contact with a plague case caught the infection and nearly all died after short illness. It was winter; rats were within their holes almost always on the top of houses with their winter food stored therein; snow on the ground prevented their immigration from one house to another, a previous flood killed almost all rats in the fields and specially in the Woolar Islands, and the rapid death of plague cases left no time for the germs to settle and infect the soil for the rats to be infected therewith. Owing to these causes no mortality among rats were observed. In fact, not a single sick or dead rat was found in any of the infected places, though close watch was kept. To this may be attributed the limited spread of the epidemic and its rapid subsidence.

In a Kashmir winter, fleas, flies and biting insects are inactive. If the type was bubonic there would have been more chance of rat infection, and prolonged epidemic and its greater spreading through infected dwellings, linen and clothes.

The epidemic in Kashmir has proved that plague bacillus is unaffected by cold per se.

Inoculation

Every attempt was made to persuade people to be inoculated. In Srinagar the popular feeling was just beginning to be favourable when fortunately plague abated and with it the zeal cooled down. A large number of men were inoculated in and near the infected villages.

We were ready with 13,473 doses of the lymph.

In Srinagar a gang of 8 coolies were inoculated before employment in disinfection work and disposal of dead bodies. Of these one caught plague 21 days after inoculation and died. Symptoms began usually four to five hours after inoculation commencing with slight feverishness and signs of local inflammation. General discomfort and pains about the joints with headache followed within 24 hours. Temperature in large majority of cases did not go up higher than 102 F; though in a few cases it reached up to 105F. The high temperature and other symptoms usually began to subside after 36 hours.

The inoculated part remained tender for about a week. There was no untoward symptom of any kind except in one case in which cellulites extending down to the forearm occurred and the fever continued for a few days. It was a case of chronic malaria. In some indigestion with diarrhoea was noticed for three or four days. All inoculations were done under strict antiseptic precautions.

Conclusions

The plague lasted in Kashmir from November 1903 to August 1904, but the virulence was only from December to March. In the city of Srinagar its duration was for one and a half month only, the total number of cases were 56, all fatal.

In the districts there were altogether 1,443 cases with 20 recoveries. The recoveries being bubonic cases, which was seen at the end of the epidemic.

There are people who say that this successful suppression of the disease was attributable chiefly to the nature of the climate, the altitude of the country (5,200 ft.) and other favourable physical causes. This to my mind is quite an unwarrantable claim. It is due entirely to the fortunate circumstance of our being allowed in the case of Srinagar to deal with the first few cases in a drastic manner, viz, burning the first few foci and segregating the contacts.

In the districts evacuation of houses and segregation of contacts proved the desired result.

Though not venturing to draw any conclusion from it, I must mention the fact that throughout the course of the epidemic in Kashmir no mortality was noticed among rats, though a very careful watch was kept. The fact that almost all cases, with a few exceptions, were of a pneumonic or septicemic kind naturally raises the question why it was so.

I think that when the mode of infection is through blood by fleas, blood parasites, etc, the type is usually bubonic, while if the infection is directly inhaled by lungs through sputum, etc, the type assumes the virulent pneumonic or septicemic type. In a large number of cases the two latter types are undistinguishable.

Instances after instances were seen in which an infected hut was evacuated and disinfected by mercury and phenyle; the house was locked up, a month or six weeks after it was opened and occupied, immediately after a new case would occur. The disinfection therefore was ineffectual.

The question arises how did the germs, unaffected or untouched by the disinfectants, live and retain their vitality for six weeks. In almost all instances there was no grain or food of any kind in the rooms, no dead rats were found, nor any cattle lived therein: why did not the germs die of inanition?

It is not also known what variations in morphological and cultural characters occur, it any, during the saprophytic existence. The solution of these bacteriological problems connected with plague bacillus will greatly help in the practical measures for combating with the disease.

The disappearance of plague from Kashmir, no doubt, points to the theory that the parasitic bacteria of plague failed gradually to transmit their species through and maintaining their existence in the animal body. They were gradually reduced to a saprophytic existence only, and thus the pathogenicity ultimately disappeared.

I also venture to put a suggestion that the bacillus pest is has the same relation with pneumococcus (both Friedlanter’s and Fraenkel’s) as B Typhosus has with B Coli communis, at least clinically, both probably containing analogous intracellular poison.

To my mind the true light on the proper method of suppressing plague is therefore yet to come from the Bacteriological Laboratory.

I took special care to find out if during the prevalence of plague there was any special prevalence of pneumonia amongst the people of infected localities. The result of the enquiry distinctly showed that it was, and one instance was found in which three members of a family died one after another of acute croupous pneumonia.

There could be no mistake: these cases were kept under my personal watch, and they were found to run through a typical course of acute croupous pneumonia.

(The write-up appeared in The India Medical Gazette in April 1907. A Health Officer for Calcutta Public Health Society, Dr Rai Bahadur A Mitra (b 1858-) was appointed the Chief Medical Officer and Sanitary Adviser of Kashmir in 1885 by Maharaja Sir Pratap Singh. Later, he became the Minister of KashmirPublic Works. He died of diabetes.)