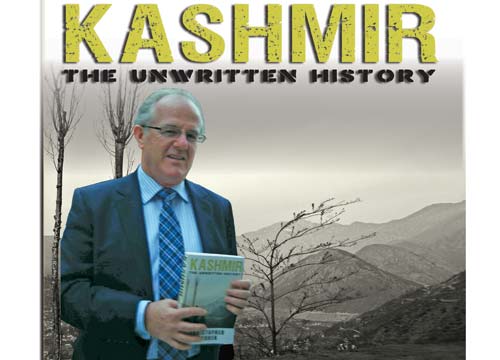

That Poonch rebellion and not the tribal raids were fundamental to the slicing of erstwhile Kashmir state is an established fact. But Christopher Snedden’s ‘In Kashmir: The Unwritten History’, launched in Delhi last week, is important for its scholarly critique of some of 1947s watershed events that were otherwise obliterated from the post-partition narrative.

In 1947, people in Jammu Province engaged in three major actions that divided J&K and confirmed that the princely state was not deliverable in its entirety to India or Pakistan. The first was a pro-Pakistan, anti-Maharaja uprising by Muslim Poonchis in western Jammu that ‘liberated’ large parts of this area from the Maharaja’s control. The second was major inter-religious violence in the province that caused upheaval and death, including a possible massacre of Muslims. The third was the creation of the Provisional Azad (Free) Government in areas liberated or ‘freed’ by the Poonch uprising. These three actions all occurred during the ten-week interregnum between the creation of India and Pakistan on 15 August 1947 and Maharaja Hari Singh’s accession to India on 26 October 1947.

Each was initiated, and then largely undertaken, by J&K state subjects—local people of J&K who had a legitimate right to be in the princely state. The only exception was the inter-religious violence which, while initiated by state subjects, was also fuelled by the arrival of refugees, external and internal, moving into or through Jammu Province, especially via the Sialkot-Jammu-Pathankot corridor.

The Jammuites’ three actions in 1947 were highly significant. They caused a large number of deaths, many casualties and much dislocation. They divided Jammu Province politically, physically and militarily into pro-Pakistan and pro-Indian areas. They instigated the ongoing dispute over J&K’s international status—the so-called Kashmir dispute—before Maharaja Hari Singh’s accession to India.

While the Jammuites’ post-Partition actions in 1947 were significant, we know little about them. This is partly because India, especially, and Pakistan have generally ignored these. There are serious information gaps concerning these events. Few scholars have discussed the Poonch uprising or the creation of Azad Kashmir in depth. People have been reluctant to delve into the embarrassing inter-religious violence in Jammu in 1947. Consequently, we know little about the violence committed against Muslims in eastern Jammu—not to mention of significant violence committed against Hindus and Sikhs in western Jammu. The evidence confirms that the people of J&K—and not outsiders—instigated the Kashmir dispute.

The British departure from the subcontinent in August 1947 caused two significant changes in J&K. First, Maharaja Hari Singh lost his guarantor, the British. No longer could he impose his will, almost with impunity, on the people of J&K, knowing that the British would support him or, at worst, ignore his actions. Nor could he rely on the (British) Indian Government to control sub-continental politicians, particularly in the Indian National Congress, and neighboring populations, particularly Punjabi Muslims wanting to politically or physically assist J&K

Muslims. He could not call on the support of (British) India’s military to quell internal uprisings, as he had done in 1931, or to police J&K’s porous borders and keep out intruders. Instead, Hari Singh came under increasing pressure from the new leaders of India and Pakistan over the accession issue, over the welfare of the people of J&K, and over the release of each dominion’s respective political surrogates then languishing in J&K jails.

Maharaja was placed in a position where, in a volatile and increasingly insecure environment, he was charged with determining J&K’s future status. This decision took on added significance after Muslim-majority Pakistan and secular (but Hindu-dominated) India was created. Hari Singh was now British-free—and on his own. It created expectations among the people of J&K that soon they also would be joining one of these new dominions. This, in turn, put further pressure on Hari Singh to make an accession.

Partition process affected Jammu Province most of all. This province was contiguous to Punjab, where violent and brutal inter-religious activity was occurring. Some of these dislocated souls travelled via a major land route that ran from Sialkot, through Jammu City, to Pathankot, thus connecting the two new dominions. The presence of these refugees and their harrowing stories further agitated Jammuites who, like their Punjabi neighbours, were highly volatile throughout 1947. —