Partap Singh occupied Kashmir throne for 40 years. But historian Ashiq Hussain Bhatsays the actual ruler was the British Resident who had limited despot’s authority taking advantage of palace squabbling and intrigues

Dogra Maharaja Partap Singh ascended the Kashmir throne in September 1885 and died in September 1925. Thus he sat upon Kashmir throne for 40 long years.

But the fact is the British scarcely allowed him to exercise authority on “his” State although they had sold and transferred Kashmir State on March 16, 1846, into the possession of Dogra dynasty. Even when Partap Singh was mourning the death of his father, Maharaja Ranbir Singh, the then British Government of India decided to install a Resident in Srinagar.

British had, right from the day of Sale of Kashmir to Gulab Singh, Partap’s grand-father, kept a close watch on the State especially its northern frontiers. In 1852 they installed an Officer on Special Duty in Kashmir followed by the appointment of Political Agents in Ladakh and Gilgit in 1867 and 1877.

During Pratap Singh’s reign, British ruled Kashmir State directly. They justified their intervention in Kashmir on the ground that Pratap Singh’s court was a hotbed of intrigues among his brothers Amar Singh and Ram Singh; and his ministers Lachman Das, and Gobind Sahai; and that his administration was, therefore, inefficient. They also accused him of setting up secret contacts with the Afghans, the Russians, and with former boy Maharaja of Lahore, Dhileep Singh, whom the British had exiled to England in 1853 and who was then a grown-up man aspiring, so the British believed, to re-establish, with Russian help, Sikh rule in Punjab (p 29 Kashmir A Disputed Legacy by Alastair Lamb).

Dhileep Singh was in Russia in 1888. And the same year a Russian Agent, Captain Gromchevsky, accompanied by a six-man Cossack escort, entered Hunza where its Ruler, Mir Safdar Ali, received him as his guest (p 449 The Great Game by Peter Hopkirk). Sometime later three French travellers entered Chitral. The British read these incidents of infiltration as proof that the northern frontier of their Indian empire was too porous.

So at that point of time, the British Government of India maintained that if the defence of Gilgit, the most important border post in India’s north-western line of defence that ran from Quetta to Gilgit along the Afghan border, were left in Partap Singh’s hands it would undermine the spirit of British Forward Policy and of the Great Game against Russia. So they revived Gilgit Agency in 1888 which they had abolished in 1881 (p 29 Kashmir A Disputed Legacy by A. Lamb).

In February 1889, the Resident Colonel Parry Nisbet stripped Partap Singh of government authority on the charge of keeping treasonable correspondence with the enemies of British Empire. The event later became the subject matter for Rudyard Kipling’s famous Great Game novel, Kim.

The Resident declared him unsuitable to rule this strategically important State. He set up a 4-member Council of Regency to be headed by the Resident with Amar Singh as a senior member. Amar Singh had assisted the British conspiracy against the Maharaja by confirming the veracity of the alleged correspondence that Partap Singh was accused of keeping with enemies. Other members of the Council included Ram Singh, Pandit Bagh Ram, and Pandit Suraj Koul, a Kashmiri Pandit (p 17 The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir A S Anand). Koul was part of the conspiracy against Maharaja hatched by Parry Nisbet at Sialkot with Amar Singh.

The British, however, were hardly concerned about the welfare of the people of the State. Their aim was to construct imperial roads to link frontier areas of the State to Indian hinterland and to reorganize State military force to use it for the defence of their empire at the cost of the State exchequer.

Thus during World War-I, they recruited 51000 wartime soldiers from Jammu Province and also siphoned off 10 million rupees from State treasury for their war effort (p 40 The History of Jammu and Kashmir by Mohammad Saleem Khan).

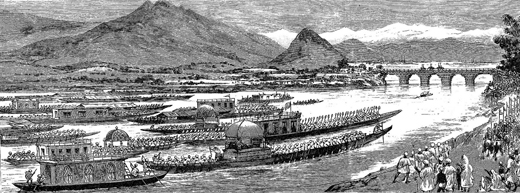

Besides, they used State forces called Imperial Service Troops in their military campaigns against Hunza, Nagar, Chilas, and Chitral during the 1890s (p 30 The History of Jammu and Kashmir, Mohammad Saleem Khan; p 473 – 491 The Great Game Peter Hopkirk).

The Resident controlled Administration spent heavily on reorganization and maintenance of State Army, reduced its strength from 22000 men to 7500 men whom they divided into two branches, Regular Troops and Imperial Service Troops (p 275 The History of Jammu and Kashmir, Mohammad Saleem Khan). Also, they spent heavily on the construction of imperial roads such as Rawalpindi to Srinagar to Gilgit and to Ladakh; on Sialkot – Jammu Rail Link; and on the comforts of Maharaja’s household.

On the contrary, they spent little on education, transport, public health and hygiene, irrigation works. Common people especially the Muslims of the Valley continued to be victims of exactions of jagirdars, chakdars, and Government officials; of forced labour; and of indebtedness to moneylenders.

Interestingly, the British did not lend support to Settlement Commissioner Andrew Wingate who recommended in 1887 that proprietary rights on land should be granted in favour of the tillers (p102 The History of Jammu and Kashmir, Mohammad Saleem Khan). And when Andrew Wingate faced opposition from jagirdars, he was constrained to leave the State lest he might meet the same fate as Lt Thorp and Agent Hayward.

The British especially Colonel Parry Nisbet did not care what happened to common people so long as British imperial interests were safe. When in order to appease the then Maharaja and his feudal lords, the successor Settlement Commissioner Walter Lawrence (appointed May 1889) recommended to the Resident controlled Administration that in no case should the proprietary rights on land be granted to tillers, his recommendations were accepted (p 110 The History of Jammu and Kashmir Mohammad Saleem Khan; also p 430 – 432 The Valley of Kashmir, Walter Lawrence).

On his transfer from Kashmir, Parry Nisbet went to Muree via Jhelum Valley Road, the Darbar conscripted hundreds of Kashmiri Muslim peasants on beggar to take his baggage, which included a houseful of furniture, on their backs for hundreds of miles from Srinagar to Jammu over 9000 feet high Banihal Pass. It took them weeks to execute the task and the hardships they must have suffered could be imagined (p 158 Condemned Unheard by William Digby).

The Resident controlled Administration imported Punjabis to serve in the civilian administration (p 129 The History of Freedom Struggle in Kashmir by P N Bazaz). Kashmiri Pandits and Jamwal Dogras resented these measures on the ground that employing ghairmulki (foreigners) in the State will hit the livelihood opportunities of mulki (State people). Together the Pandits and Dogras started a movement “State for State’s People” (also called “Kashmir for Kashmiris”) demanding that employment in the State should be given to them rather than to Punjabis. In response to this movement, it was the then successor Ruler of the State, Maharaja Hari Singh, who passed in January 1927 the State Subject Law which provided that mulki would be preferred to ghairmulki in cases of employment in Government service (p 24-25 The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir by A. S. Anand).

Thus the English Resident was the de facto ruler of Kashmir. He wound up the Council of Regency in October 1905 when the Russian threat was mitigated by Russia’s crushing defeat at the hands of Japan in 1904 in the Pacific Ocean. The Russo-Japanese War caused a drain on Russia’s resources in addition to the loss of 90,000 men. Even then the Resident restored Partap Singh’s authority only partially (p 20 The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir by A S Anand). The understanding was that Maharja would not take any decision of consequence without first seeking permission from the Residency (p 34-35 The History of Jammu and Kashmir by Mohammad Saleem Khan). Amar Singh, his rival brother, would keep a close watch on him.

During the Great War (1914 –19) Russia was an ally of Great Britain against Germany. But the Communist takeover of Russia in 1917 and their making peace with Germany changed the dynamics of global strategy. By 1920 Communists were in firm control of Russia. Russian expansionism was now displaced by Soviet ideology of Marx and Lenin which was even more dangerous because this ideology had its votaries in midst of the British Empire.

So Kashmir once again became the centre stage of British rivalry against the Soviet Union. Its Maharaja was suspect in their eyes. So as to increase their role in running government affairs they made him establish, in 1922, a Council of State with Hari Singh, son of Amar Singh, who had meanwhile died in 1910, as its Senior Member. He would also be Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces (p 23 The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir by A. S. Anand). Thus, the British Resident would keep Maharaja Partap Singh’s authority in check through the device of Council of State.

Partap Singh and his feudal lords treated the Muslim majority of the State as mere beasts of burden that did not deserve even a square meal. The Maharaja, it is said, did not like to see a Muslim’s face before noon (p 27 & 203 Allama Iqbal aur Tehriki-Azadi Kashmir by Ghulam Nabi Khayal). Muslims were neither mulki nor ghairmulki. They were beasts of burden who were supposed to work and suffer starvation in return. But even their endurance had a limit.

In July 1924 Silk Factory workers, all Muslims protested against inhuman working conditions and derisory wages. The Factory had been set up in 1907. It employed 5000 Muslim workers who worked under management entirely manned by unscrupulous Kashmiri Pandits. It produced the largest quantity of silk yarn in the world. Partap Singh’s government reacted to the protests with disproportionate violence and even exiled those eminent people who dared to submit a memorandum of grievances to Viceroy Lord Reading during his official visit to Kashmir that year (p 87-88 Kashmir A Disputed Legacy A. Lamb).

Partap Singh died in September 1925 a thoroughly frustrated man. During his last years as Maharaja, he tried his best to forestall Hari Singh’s ascension to the throne – his son had died soon after birth – by adopting Jagat Dev Singh, a member of Poonch ruling family and a descendant of Gulab Singh’s brother Dhian Singh (p 58 Kashmir: Birth of a Tragedy A Lamb). But the British were extremely indulgent towards Hari Singh as they had been towards Amar Singh. They refused to recognize Jagat Dev Singh as heir apparent thereby paving the way for the ascension of Hari Singh.