Skipping the raging debate over lethality of the non-lethal weaponry – in vogue for six years now, Saima Bhat meets pellet blinds in their colourless tunnels to understand how hunter gunning in Kashmir is changing the lives of the victims otherwise living on the margins

Pic: Saima Bhat

In February 2014, Mehbooba Mufti, then leading the opposition staged walkout from the state legislative assembly over the use of pellet guns and pepper gas on Kashmiris. She demanded a blanket ban on the use of ‘non-lethal’ weaponry and shifting of injured youth outside the state for advanced treatment. Non-lethal weapons were part of her campaigning armoury as well.

A year later, as her party led PDP-BJP coalition is governing J&K, pellet guns are back in focus for their lethal use and government’s apparent indifference towards victims.

On May 22, eighteen-year-old Arman (name changed), a twelfth standard student, who earns as a medical agent to fund his studies, was hit by pellets in Rajouri Kadal when he was on his way to distribute new hand sanitizer samples to chemists.

“I was riding my office bike and my medical bag was in front of me. I did not see any tensions around. When I reached near the Chowk, out of blue I was shot with pellets. Instantly, I moved my face to the other side to save it,” says Arman. But one pellet had stuck his left eye, others to the left side of his neck, arm and skull. “It was a direct hit. A targeted one you can say as there was no mob around.”

The next thing that Arman recalls is that he was in Sheri Kashmir Institute of Medical Science (SKIMS) Bemina, where he was admitted and asked to undergo an emergency surgery. But to avoid police case, that usually follows in such cases, he left the hospital and preferred to stay home.

One week later, Arman is restricted to his room. The only source of light, a small window, located on the eastern side of the room is covered with thick curtains. “I cannot bear light,” he explains while pointing towards his left eye that still gives bloodied look. “It is blood! When I take some stress or simply think about anything seriously, blood starts coming out from it. I cannot see anything from my left eye except an occasional flash of white flash light.”

Apart from Arman’s parents and close family nobody knows about his injuries. “A few days after I was hit, my results came out. You won’t believe I was praying to God that I should not get enough marks otherwise all my relatives would come to congratulate me. I had passed my 10th standard with distinction,” says Arman. “I can’t sleep properly as left side of my skull and neck still has pellet pieces inside.”

When this reporter visited Arman, he was just back from a private clinic where an injection was given directly into his cornea without giving him local anesthesia. He was withering in pain.

A few kilometers away teenager Danish, 17, was hit by pellets on June 18, 2014. That day Kashmiri youth protested against atrocities in Gaza. Around 150 pellets had hit his body from head to toe.

Hailing from a modest background Danish started working from an early age. “I was just 9 year old when I started working with my uncle. He decorates houses for marriages,” says Danish.

Before his injury Danish would add around Rs 3000 a month to his family income – more than what his father earns. His father sells floor sheets on cycle.

Danish has undergone three surgeries – one in SKIMS Bemina and two in Amritsar, Punjab. Doctors in Amritsar had advised him to come again for another surgery in which a lens will be put in his eye. “They (doctors) told me that chances are I might be able to see the world again. But there is no guarantee,” says Danish.

Three of Danish’s friends, who too were hit by pellets on that day, had undergone surgeries outside J&K. But the results were disappointing. “I know I can’t see again. So what is the fun of spending money,” says Danish.

But Danish’s mother says that the reason they are not opting for another surgery is lack of finance. “We have sold everything we had for his earlier surgeries. It cost us around Rs 3 lakh. Now there is nothing left,” says Danish’s mother.

“Last time my brothers and Danish’s uncles came forward and contributed for his treatment. But I can’t ask them again for help. I am planning to visit separatist leaders, may be they will help my son. But I am not sure if they will help at all as I belong to a National Conference patriot family. NC people too won’t help because my son was hurt during stone pelting,” says Danish’s confused mother.

After the injury Danish avoids getting on top of the buildings to place decorative buntings. “I am afraid of climbing now because my vision is blurred. I can’t see from my left eye and my right eye’s vision too gets distracted. I fall quite often while climbing stairs. I have to be doubly sure if I have placed my foot correctly on a staircase,” says Danish.

Even riding a bike, that used to keep him mobile and help him reach his workplace quickly, is now difficult for Danish with such blurred vision. “Life is long and it’s my reality, I have to live with it. That is why I prefer to return home much before dark as I can’t see properly from even my right eye in the evening,” says Danish painfully. He continuously feels pain in his eyes and complaints of developing ‘pressure’ which aggravates his headache.

Earlier Danish used to attend three functions a day but since pellet hit his eye, he manages only one in a day.

Post-injury he has given up cricket, his favourite sport. “I tried playing once, but when the ball was thrown at me I couldn’t judge it properly. So I left the field,” says Danish.

Danish’s mom is melancholic. “I wish to donate my eyes to Danish. He is my eldest child; I can’t see him like this. But we don’t have enough money for such kind of a surgery. I know he can’t see, but I still hope that he will get his vision back someday.”

The use of shot guns or pellet guns became norm since 2010 unrest. Even though doctors call the damage caused by pellets deadlier than bullets but the High Court sees it “non-lethal”. A PIL, against the use of these weapons, was dismissed by the High Court. Later, the PIL was re-appealed and argued with more cases but is pending disposal. Litigant Manan Bukhari, head of the Human Rights Division APHC, told Kashmir Life that he will take the case to Supreme Court.

Data revealed in response to an RTI suggested Kashmir’s two main hospitals SKIMS and SMHS, from 2010 to October 2013, 165 people suffered serious pellet injuries. Of them at least 12 lost their eyesight partially or completely.

“The number of pellet victims is much more than what these hospitals reveal,” says Bukhari. “They haven’t given us exact figures and there are many injured who don’t even go to these hospitals fearing the raid of state forces.”

Many injured claim their doctors advised them going out of J&K for treatment. “Doctors at SKIMS Bemina and SMHS only do stitching of injured eyes but then ask them to move out of state. I won’t say patients after moving out of state get their vision back but at least they have machinery there to operate upon them. Here we lack basic facilities,” says a parent of one such patient.

Despite a government order that pellet guns be used sparingly in Srinagar, they are used regularly in Old Srinagar and across some particular villages. One pellet cartridge contains 400-500 pellets, small ball bearings. Cartridges come in grades of five to 12, five being the largest, fastest and with the widest range.

“Though written instructions have been given to use the number 9 pellet for crowd control, as it does not cause lasting damage, the directive isn’t followed. In villages, we see number 6 and 7 pellets being used regularly. Most sensitive police stations in Kashmir receive regular supplies of number 5, 6, and 7 pellets,” a newspaper reported.

In May 2015, the state run hospital, SMHS installed its first Vitrectomy equipment claiming that such injuries will be dealt locally. “We had such machines in our state available but what doctors do is they remove the pellet and treat in case of haemorrhages. You tell me what we can do when patients come to us when their eyes are already blasted by these pellets,” says senior ophthalmologist Dr Bashir Ahmad. “We don’t do corneal transplants here because we don’t have donors. Otherwise we have high definition machinery available here and every kind of injury is treated here.”

“These pellets hit eye with high velocity and it creates huge damage to the eye, which is irreparable in most of the cases,” explains Dr Afroz Khan, associate professor and SMHS’s ophthalmology head. “Parts of eye can be replaced in Kashmir and outside as well but nobody in world can do anything when the gel or fluid of an eye is lost.” In majority of pellet eye injuries that fluid was lost, he asserts.

On July 12, 2013, carpenter Mushtaq Ahmad Najar, 45, was hit by pellets in Nowhatta while buying vegetables. “I was not aware that boys were pelting stones at police. I realized my mistake only when I saw young boys running for cover. I too started to run but it was late I guess,” recalls Najar. “First police shot in the air and then directly towards the boys. And in that chaos something hit my body, from face to chest. Confused, I rushed straight to SMHS hospital where doctors said one pellet has pierced through the cornea of my left eye”.

A resident of Malaratta, Najar is the lone bread earner of his family comprising his parents, wife and a son. So far he has undergone two surgeries in Kashmir, one at SMHS and another at a private clinic, but his dark eye couldn’t turn colourful again.

Before that incident, Najar would work throughout the week so that his son can have a better life and future. But now he is planning to change his profession. “Every day is a struggle for me. Other carpenters, whom I had once taught, scold me for even small mistakes. I don’t do it deliberately but they don’t understand,” says Najar. “I work for just 3 to 4 days a week that too for lesser wages. For rest of the days I stay at home because of the pain.”

Doctors have advised Najar to use two spectacles: one for near vision and another to see far away. A few months back his toe hit something on the road and he fell on the ground hitting his head and leg. His glasses for near vision got damaged and now he is managing without it. “A new pair of spectacles costs around Rs 500. I cannot afford to spare that much from my limited earnings. After all I have a family to look after. Cannot let them beg on streets,” says Najar.

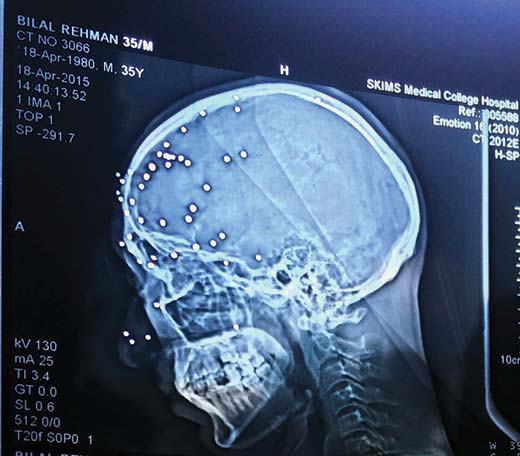

On April 17, 2015, Bilal Rehman, 35, father of three sons, was hit by pellets on his left eye, nose and head near the Jamia Masjid. He had gone to Jamia market looking for cheap school uniforms for his kids. “It was Friday and most of the shops were closed for afternoon prayers. I too went inside the mosque to offer prayers thinking that on my way out I will buy uniforms,” says Rehman, a pashimina shawl weaver by profession.

After the prayers when Rehman walked out, he found main gate of the mosque locked from outside. “There were policemen on the other side of the gate firing at people coming out of the Masjid. There was no stone pelting going on in the area as everybody was busy with offering their prayers,” claims Rehman.

Within no time there was chaos all around. Everybody was running for his life. “Suddenly I started feeling pain and something was coming out from my face. When I checked, it was blood,” recalls Rehman.

Rehman was not alone; at least ten others were hit by pellets on their faces and eyes that day. “One among the victims was a 12-year-old boy who was accompanying his father for prayers. He was hit by a pellet and fell on the ground. In the chaos people ran over him. I still remember his face,” says Rehman.

Rehman was taken to the hospital where doctors diagnosed him with Vitreous haemorrhage, leakage of blood into the areas in and around the vitreous humor of the eye. The vitreous humor is the clear gel that fills the space between the lens and the retina of the eye. “Doctors first stitched my eye so that liquid stops coming out of it. But later, they advised me to go to Amritsar for further treatment,” says Rehman.

“I managed some money from relatives and friends and went to Amritsar directly where I was operated upon. They (doctors in Amritsar) have guaranteed me that I will get my vision back. But it has already been a month and I am still in the tunnel,” says Rehman.

Once Rehman was back, his eye started aching again and he consulted a local doctor in civil lines area, who advised him to rush immediately back to Amritsar as his vein had got blocked. “As I reached Amritsar in next 12 hours doctors there just changed my eye drops. Imagine a local doctor couldn’t rectify a small issue for which I had to fly in emergency,” says Rehman.

So far Rehman has spent around Rs 2 lakhs on his treatment but what he sees from his left eye is just the outline of people sitting on his left side. Rehman has to manage a family of seven members including his aged parents with his meager income.

Before leaving for market to buy uniforms for his kids Rehman had left an unfinished Pashmina shawl back home. “I was hoping to complete it in the evening,” says Rehman regretfully.

After he was hit by pellets Rehman decided to handover the incomplete shawl to his friend for final touches. “It was such a painful moment for me that I cannot describe in words. I was not only passing a shawl but surrendering my talent, my pride, my livelihood,” says Rehman while holding his tears back. “I cannot even cry!”