Terrified by a threat, 22 men, women and children of an extended family huddled together to save their skin in the summer of 1998. But the death came knocking at their door past midnight with a barrage of bullets silencing 19 of them. Somehow, three of them survived by giving the butchers a slip. Sixteen years later, survivors of one of Kashmir’s goriest mass murders tell Bilal Handoo the frustrating story of their battle for justice and a struggle for survival

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

At one fringe of Mughal road, three closely related families were living an austere life until a nasty peril decimated their lives. But before the intervening night of August 3-4, 1998 wrapped Sailan under dark blanket, one of them had heard an army major taking a vow: They won’t be able to see the next day’s sun! Major’s remark had unnerved them. As panic started petrified them, they abandoned their home and spent night at their relatives living at a stone’s throw. Down the hill they came and divided in two small groups. They took refuge at two separate residences of their relatives. But then, shifting of base couldn’t relieve them from the nightmare. At midnight when guns started blazing, 19 out of 22 members present in two residences were butchered. Three members survived miraculously, only to recount the horror of the night.

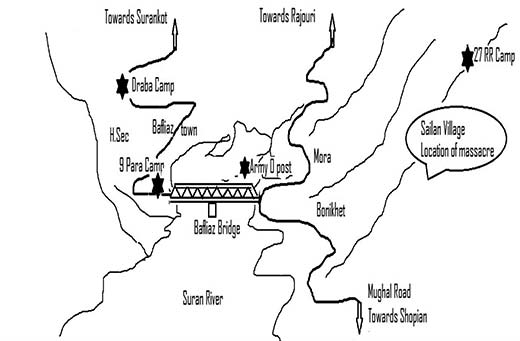

Men in fatigues had come to hunt down a militant, Imtiyaz, who had killed Zakir Hussain (the informer of 9 para army) early that day in Sailan, 14km from Surankote in district Poonch. They couldn’t trace him. And instead, killed 19 members of Imtiyaz’s relatives—his parents, siblings, uncles, aunts and first cousins. A few hours before the bloodshed, villagers had quoted the army major, saying: “It wouldn’t have pinched me so much had Imtiyaz killed my officer, but by killing Zakir, he has invited a great trouble for him.”

It was Lassa Sheikh (Imtiyaz’s father) who became the first casualty of what later came to known as “Sailan Massacre”. It is said that Lassa’s 15-year-old son Imtiyaz (class 9 student) was the first among young Kashmiri to cross over to Pakistan administered Kashmir from Sailan in 1996.

Imtiyaz ‘ran away’ without informing his family along with a group of his friends. A few months later when he returned from ‘training’, his father thought it as ‘dangerous act’ and handed him over to the local police authorities hoping they would ‘teach him a lesson’. He was (as was common in ‘militancy’ related cases) handed over to military authorities, who released him after several days of “brutal interrogation”. After his release, he was subjected to frequent surveillance. His family members bore the brunt of constant raids and harassment at the hands of local armed forces and their informers in the area.

A few months later, Imtiyaz was rearrested on “weapon possession charges”. But a few weeks later while being taken for court hearing, he ran away from police custody and took refuge in the hilly countryside. After that ‘heroics’, Imtiyaz became a ‘real mujahid’ for locals. He was no longer a school boy. But the rising lieutenant of the local wing of the Hizbul Mujahideen, operating from the hills and forests.

Zakir Hussain from the village of Mora (across the Nallah from Sailan) was a few years older than Imtiyaz. At a fairly young age, he began to work as a coolie with the army camp of the 9 paratroopers at Bafliaz. He soon grew in stature to become the army’s main ‘source’ in the area. Some accounts state that Zakir had received ‘militant training’ and thereafter begun to work as an ‘army informer’. However, locals believe, he was never an active militant, but was ‘planted’ to associate with certain members of armed groups in order to infiltrate and inform about them.

It is believed that ethnic and religious minorities, including Gujjars were actively recruited as part of the counter-insurgency information and intelligence gathering network during that period. And, it is likely that this was the trajectory that Zakir’s (Gujjar) biography followed, rather than of being a surrendered militant.

Zakir was soon appointed as a special police officer (SPO) under the direct command of Superintendent of Police, Sevak Singh of the special operations group (SOG). He was attached to the local army (9 paratroopers) camp at Bafliaz, a few months before the massacre. After that, he was regularly accompanied by an entourage of four other such SPOs or ‘informers’: Mohammad Younis, (alias ‘Tiger’), Mohammad Rafiq Gujjar (alias ‘Pathan’), Maqsood Ahmed Khan and Mohammad Akbar Malik.

This band of men led by Zakir “tormented” residents and shop keepers in Sailan, Bonikhet, Chandimarh and Bafliaz. They demanded goods and services for free, interrogated or harassed young women and school children. One resident of Sailan recalls witnessing Zakir pistol whipping and beating an old man wearing a red handkerchief on the street. Later the witness learnt that the man was Zakir’s own uncle.

By the early 1998, the authorities had launched an intensive search operation for Imtiyaz backed by Zakir and his associates. One family member of Imtiyaz who survived the massacre referred to it as an ‘underground’ rivalry. Young men from Imtiyaz’s family in Upper Sailan were ‘picked up’ for ‘interrogation’ about his whereabouts, several times. One of the survivors and Imtiyaz’s sibling Maqsood Sheikh was detained and beaten four or five times. While his cousin Mohammad Shabir (another survivor) then 18-year-old remembers being interrogated twice by 9 para army personnel.

On the morning of August 3, 1998, Zakir and his group were seen stationed at the Behramgala police check post (a kilometre or two North of Sailan village) on the Mughal Road. They were searching for Imtiyaz, pulling passengers out of vehicles and checking them. Meanwhile, Imtiyaz and his friends were bathing in the Parnai, a small rivulet that flows between Sailan and Behramgala.

Zakir and his group came to know about Imtiyaz’s presence. They headed up the road towards the Bafliaz camp (possibly to inform the army) in a bus that they commandeered at the check post. Imtiyaz and his group received advance information of Zakir’s movements from locals. They, in turn commandeered another local bus, emptying it of all passengers except the driver and bus conductor, and headed towards Sailan to confront Zakir. At some distance past Sailan, Zakir asked the driver to turn his bus around and began travelling towards Sailan. Probably he had learnt Imtiyaz’s presence in the village through his wireless set.

The two buses then started heading towards each other. Residents of Upper Sailan saw Zakir seated next to the driver and jumping off the bus. Just past the village of Sailan, on the curve of the road by the Bafliaz Bridge near the village of Bonikhet, gunfire broke out. Zakir was seen running towards the Bafliaz camp, firing backward with his pistol. Imtiyaz was also seen firing back in the direction of the gunfire from the moving bus. The bullets hit Zakir, who fell to the ground. Imtiyaz and his group, then leapt off the bus, and fired more shots at Zakir’s body.

After Imtiyaz and the others disappeared into the surrounding thickly forested hillsides towards Mora, uniformed personnel from the army camp across Bafliaz Bridge showed up. They surrounded the body, began shelling and rounded up the bystanders and villagers, demanding information. They were visibly angry and “extremely abusive”. A man identified as Major Gaurav (locally known as Major ‘Goora’) was leading them.

Soon Zakir’s father arrived who knelt by the body of his son. The elder while cursing his fate, blamed the army for his son’s death. He vowed that he would not allow his burial until the death was avenged. Major Gaurav attempted to console him. The major is specifically remembered as having said that he would ensure that Imtiyaz would pay dearly for this “with the lives of twenty members of his family”.

As evening fell on Sailan later that day, Imtiyaz’s extended family grew extremely anxious. And later when evening merged with night, the terrified family decided to abandon their home fearing a late night ‘crackdown’ or worse. When Mohammad Shabir, then aged 18 returned from Bafliaz, where he had gone to collect his school certificates, he found the elders of all three families – his father (Ahmad Din), his uncles: Lassa Sheikh (Imtiyaz’s father) and Hassan Mohammad, engaged in a tense and anxious discussion.

He informed them that he had seen Zakir’s body at Bonikhet and had himself heard the army major making loud and public threats. Maqsood (then about 18) Imtiyaz’s brother and an eye witness to the chase and Zakir’s killing had also returned from Lower Sailan. On his way home, he had met Hajji Abdul Rashid (the bystander who had seen Zakir’s body being taken away to Bafliaz camp). Rashid had told Maqsood that his family should flee immediately, as he had heard army personnel making threats that they ‘would not live to see the dawn’.

Fearing reprisals, some of the younger males had left the houses, given their past experience that torture and more severe harassment was generally directed at the males rather than at women and children. One of Imtiyaz’s cousins, Afzal, (the son of his paternal uncle Hassan Mohammad) decided to stay the night at his married sister’s house nearby, while Latief (Shabir’s brother) remained in Surankote.

That night, Imtiyaz’s entire family moved their belongings and valuables to leave the village indefinitely. But as it was growing late and dark, besides an undeclared curfew was imposed, they decided to stay the night at Hassan Mohammad and Ahmad Din’s homes and leave the next morning.

The members of the three families huddled together in the two houses. The adults were unable to sleep and stayed up talking about the death of Zakir and their fears of a revenge attack or further harassment. Abdul Ahad, then 20, (and one of the survivors of the massacre) recalled that at 12:30 AM, someone knocked at the door. Two uniformed men with covered heads donning military fatigues barged in. It was ‘Tiger’ and ‘Pathan’, Zakir’s associates. ‘Tiger’ asked Ahad about Imtiyaz’s family. “I replied that some of them were with us and rest at my uncle’s place,” Ahad recalls. The duo along with other uniformed men had already searched Imtiyaz’s home, but found it empty. Ahad saw the shadowy figures of about ten to fifteen men milling around in the compound through the doorway.

The men grabbed hold of Iqbal (Imtiyaz’s older brother) who was mentally challenged. After Ahad intervened, the duo left him and instead caught Maqsood. He was dragged outside, and meanwhile, Ahad managed to slip away and hid himself in nearby maize field. From there, he watched Maqsood being forced to lead the men to the house of his uncle Ahmad Din.

Maqsood was asked to call his father out of Din’s residence. “I yelled loudly, ‘open the door quickly!’ As they entered inside, a commotion gripped the house,” Maqsood recalls. “At this point, I took my chance and hid in the maize field which was over head high.”

Mohammad Shabir (Ahmed Din’s son), who was inside the house at the time when Maqsood managed to flee, remembers that around 12:45 AM, he heard Maqsood’s voice outside. “Imtiyaz’s father was about to open the door, but my father got up and asked Imtiyaz’s father to sit down,” Shabir recalls. “The two SPOs, Maqsood Ahmad Khan and Mohammad Akbar Malik came into the room.” Soon, the other two SPOs, ‘Tiger’ and ‘Pathan’ also entered the house during the questioning. “In the compound, I noticed an army man with a turban.”

After some time, they were asked to walk in a single file and were taken uphill to Hassan Mohammad’s house. Everyone was made to sit down on the ground like school children. Shabir saw a clean shaven officer talking to some of the gathered people. He was wearing an officer’s cap and a jacket, but he had no name plate. “His eyes were blood shot and he had dark skin and even more dark lips,” Shabir recalls.

The officer then started quizzing Imtiyaz’s father: “Where is Imtiyaz?” Imtiyaz’s father replied, “I have already handed him over to police. But he ran away and has not come home since then.” The officer then demanded, “Tell me the truth.” Imtiyaz’s father replied, “I am telling the truth. He went with the militants. He seldom visits the village but not to the house.” The officer then said, “Imtiyaz killed Zakir, who was a source for me.” The officer then made a gesture towards ‘Tiger’ who began hitting Imtiyaz’s father mercilessly.

“We were all watching, unable to say a word. The officer then winked at ‘Tiger’ who fired at the leg of Imtiyaz’s father,” Shabir recalls. He fell down, bleeding. His family moved towards the fallen man to help him. Shabir saw his father turning towards the army officer, shouting angrily. “I heard the army officer say: ‘Fire!’. By this time I had reached close to a small trap door. I managed to slip outside into the store,” Shabir says, “And soon I disappeared into the maize field.”

The gunshots continuously echoed for almost ten minutes. Shabir, Ahad and Maqsood stayed awake throughout the night in the maize fields. They heard cries and wails, but couldn’t do anything.

The next morning when Shabir entered the Hassan Mohammad’s house where the gun fire was heard, he slipped and fell on the floor splattered with blood. The first thing he saw was a shell of an SLR (Single Loading Rifle) gun fallen near the door. He saw a pile of dead bodies. They had been hacked and mutilated, cut to pieces. Arms and legs were lying at a distance from the torsos. Some had been hacked at the neck as well. There were axes, rods, kitchen utensils lying all over the room. There was an axe embedded in his sister Javaida’s hip.

“She [Javaida] used to be a big cry baby who would faint at the slightest bit of pain,” Shabir recalls. “I saw an axe penetrated so deep into her hip bone that two people had to hold down the body, and another person had to pull it. But they couldn’t remove it.”

He saw the dead body of Imtiyaz’s mother lying behind a large tray used for kneading dough. It had been placed upright, just like a shield. It was riddled with bullet holes. She had been shot through it while trying to save herself. He also saw his sister Zarina’s stomach hacked. She was pregnant for eight months and her baby’s arm was visible from the bore of her stomach. “I saw so many other terrible things which I don’t remember,” he says. “It was a Katle Aam! (mass murder).”

He came out screaming and crying. Near the doorway, he saw someone had left a note written in Urdu with a Lashkar-e-Toiba letterhead. It said: “Five per cent of the job is done, 95 per cent still remains.”

“I think they meant, killing Imtiyaz alone was 95 per cent of the task,” Shabir says. “The note was planted to make it look like an outside job. The army and police always have such things in their possession. But I had seen with my own eyes, that it was no outsider, no Pakistanis, no Lashkar-e-Toiba. It was Zakir’s men and the army. Everyone most of all the army and police know that.”

Ahad and Maqsood also returned and were requested by villagers to leave the village “to save their skin from army and their informers”. The young Maqsood was spotted by his brother-in-law who gave him Rs 300 and pleaded him to run away. He moved towards Shopian where his slain father had trade links. He stayed at the residence of his father’s business dealers for fifteen days before taken back to his village by his brother-in-law.

“Look, I know you are in constant touch with your brother [Imtiyaz],” SP Sevak Singh told Maqsood after he returned Sailan. “I think, it is better for you to stay tight-lipped. Otherwise, who cares these days. Anything can happen. Besides, who is there to mourn for you?” Maqsood says Singh also called the village Numberdaar and told him: “You better make him understand. Or, you know, what happened to his family.”

Each word spoken by Singh instilled fear in Maqsood who decided to stay quiet. He later heard that his brother, Imtiyaz had been killed by government forces.

Meanwhile deputy commissioner of Poonch MS Khan had heard on the morning of August 4 (a day after the massacre) that some were hatching conspiracy to destroy the bodies by ‘blasting’ the house. He immediately directed to bring the bodies down from Hassan Mohammad’s residence. After some hiccups, finally at about 12:30 PM, bodies were carried down. The bodies were horribly mutilated. There were bullet injuries, blunt force injuries, injuries by sharp objects. “I would say that there were twenty dead, not nineteen, because the baby in the womb was of a viable age and could have survived,” says Latief (Shabir’s brother). “We brought the bodies down to Sailan market, and then proceeded back to Surankote Tehsil headquarters.”

The survivors didn’t bury the bodies until some official inquiry was made. The crowd was outraged and adamant. At 8:15 PM that day, an FIR (no. 122/98) regarding the massacre, under sections relating to waging war against the state, illegal acts by enemy agents, murder and house trespass was registered at the Police Station Surankote. It blamed unidentified “foreign militants” for the killings. The FIR written in Urdu states that a gang of militants who had come from Pakistan, equipped with arms and ammunition had entered the “country” with the aim of disturbing the peace and committed murders with criminal intent.

“The statements of survivors and eyewitnesses were never properly recorded as part of the police investigations, and we were not even aware of what the FIR said,” Shabir says. But there was no way to counter the police argument. After the massacre, the survivors were left terrified and would even dread by the idea of going near the police station.

After the post mortem, the bodies were placed in the Tehsil (Revenue and Court) Complex in Surankote. The bodies had begun decomposing in the August heat. And some white solution, perhaps a disinfectant, was sprayed on them by officials. They were also hosed down by the fire brigade with water to delay the decomposition.

At about 2 AM (early hours of the August 5), SP Sevak Singh visited the Tehsil complex. He was accompanied by several labourers and stated that the bodies had to be transported to the graveyard for burial. Shabir’s brother Latief went with him to the site accompanied by several locals.

“They had dug up very small graves, hardly two or two feet long,” Latief says. “They were just planning to heap the bodies together and dump them in these shallow graves. I was so angry that I slapped him [Singh]. We even pelted stones at him. He was forced to leave.”

The survivors and locals sheltering at the complex spent the rest of the night wide awake. They stood guard besides the bodies with sticks and rods in a vigil. Meanwhile a strange rumour spread: At late night while they [Police] were digging the graves to make them bigger, a huge black snake came out of one of the graves. It was raining heavily. The policemen all got terrified and ran screaming back to the police station.

Several senior police officers and officials came to the Court complex to inspect the bodies the following day, including the present day top police official. “I shouted at him and told him: ‘My father was six and a half feel tall, how do you expect him to fit in such a small grave? Why don’t you lie down in it, and see if you fit.’ We pelted stones at the police official. He was involved in the cover up too.”

By August 5, the surviving family members took a decision to bury the bodies themselves as they were decaying rapidly. Surankote was under a state of undeclared curfew. About 500 to 600 local residents from Surankote and Sailan attended the funeral prayers read in an enclosed ground, adjacent to the graveyard.

Sixteen years after the massacre, a Mumbai based lawyer visited Sailan. She saw the nineteen graves of the Sailan victims lie in a shady corner of the graveyard with terraced paddy fields and the Suran River visible beyond them. “The graves bear markers memorialising the victims and the massacre,” says Shrimoyee Nandini Ghosh, a researcher-cum-lawyer who prepared a report on Sailan Massacre. “They are arranged in order of size. The smallest of the concrete graves, probably that of the youngest child, covers an area of barely two feet.”

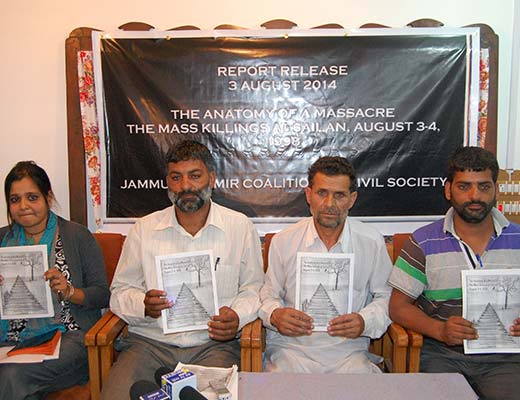

On the 16th anniversary of the massacre on August 3 this year, Ghosh with the support of Coalition of Civil Society (CCS) released a report “The Anatomy of a Massacre: The Mass Killings at Sailan, August 3-4, 1998” in association with the Survivors of the Sailan Massacre. “The idea was to document the case on community level,” she says. “I merely acted as a facilitator. But let me tell you, it was bone-chilling to learn how sleeping babies were killed.”

Survivors have moved on, but haven’t forgotten anything, Ghosh says, but it is an act of survival. “You see, impunity is complete in Kashmir. I mean why police files have been disappearing in such cases. Be it Al Faran case, Masooda Parveena case or Sailan Massacre, the police files have caught fire. Under such circumstances, we need to fight the impunity through legal process.”

A week after the massacre, then J&K chief minister Farooq Abdullah along with then union defence minister George Fernandes had come to Surankote to quell the unabating and intense protests. Shabir says Dr Farooq called him to Dak Bungalow at Surankote. “He told me: ‘Don’t tell anybody about it [the massacre]. Your life is in danger.’ He assured that killers would be punished. Fernandes also made a similar promise.”

Shortly afterwards, the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) inquiry into the case was instituted. Headed by Justice GA Kuchay, the rights body inspected the house of Hassan Muhammad where the entire killings had taken place. They saw bullet holed walls, blanket perforated with bullets, two bored metal utensils used as shields against the rain of bullets and one dirty quilt drenched in blood was also shown on the spot.

In light of their complaints of threats and intimidation from the implicated SPOs and Police, the SHRC recommended police protection to the survivors. But it was proved ineffective, as an IED blast and a fire (a part of a ‘fake encounter’) occurred at the top storey of the complex where the survivors were staying. The incident terrorised the survivors even more.

Some days before the blast, SP Sevak Singh had met Shabir along with his local lawyer Iqbal Vakil. Singh told Shabir that he should persuade Imtiyaz to surrender. Shabir told Singh that he did not know Imtiyaz’s hideout, but Singh kept on “insisting and threatening” him.

“Finally I told him that if I go into the hills looking for him, they [militants] would persuade me to take revenge for the killings. I would have to pick up arms too and join the jihad. Is that what he wanted?” Shabir recalls, “In fact, I got many offers to join the militancy, Mujahids came to our village and offered us guns. I thought about it seriously many a times. I was tempted but I refused. I did not want to participate in further bloodshed and violence. In fact, if I had a gun, Sevak Singh would be the first person I would kill.”

The reply had left Singh fuming with rage: “You better keep your mouth shut, if you want to save your life.”

A day after the blast, a constable named Khadim (who was part of the police protection team at Tehsil complex) told Shabir: “Sevak Singh had come at night and asked specifically about you. I told him that you had gone elsewhere for the night.” Besides, one Ajay Gupta of Jammu, the sub-inspector of police had objected to the “murderous” ways of the SP Singh. “He had heckled Singh in front of many people and criticized him on his face that he was victimizing and killing innocent people. But we learned Sevak Singh got Gupta killed in a fake encounter,” Shabir says. This scared Shabir who then shifted to Poonch and lived there for two or three years. On February 7, 2012, Singh was awarded life sentence in murder case of Gupta. But lately, some reports are saying that Supreme Court has released him on a bail.

Ten years after the massacre (in 2008), the survivors of Sailan felt a strange courage to fight for justice. They say, the opening of Mughal Road brought them closer to Kashmir. “The road cut down the distance between us and the valley where things are entirely different than in Jammu,” Maqsood says. The legal route was not the only one available to the survivors. But despite the threats, intimidation and frustrations, they are continuously articulating their demand for justice as a matter of rights than revenge.

In December 1998, the case was closed by the police. But Shabir and others from the village moved the High Court on Nov 2, 2011. The High Court admitted the petition on Feb 8, 2012. Then on May 22, 2012, a complaint was filed before the SHRC by the family members alleging that following their move to the High Court for re-investigating the case, the four of the alleged SPOs: Mohammad Younis ‘Tiger’, Mohammad Rafiq ‘Pathan’, Mohammad Akbar Malik and Maqsood Ahmad Khan were constantly harassing family members of the victims of the massacre. They asked for the security from the “constant victimization”.

Maqsood Khan then SPO has taken over as an officer in CID wing of police in the Surankote. While Mohammad Akbar Malik another SPO is presently a Head Constable with SOG wing of police in Surankote. Shabir says Malik had told some villager that he would shoot them (survivors).

‘Pathan’ is presently working in district police lines Poonch. “He has also told many people that whenever he would get a chance he would shoot us dead,” Maqsood says. “‘Tiger’ who is presently working with Army at Draba Camp in Surankote has also threatened to eliminate us.”

Surprisingly, the survivors were told on September 19, 2012, that the office of the Sub Divisional Police Officer (SDPO), Mendhar (where the case file was last traced) was gutted in a fire in September 2010 during the agitation against the ‘desecration of the holy Quran in America’. The only remnants of the police investigations 1998 were a ‘shadow’ case diary with the last entry dated June 30, 2006, written by Deputy Superintendent of Police.

Based on this report (on November 21, 2012) the High Court ordered a re-investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s apex investigative body. After some delays regarding the transfer of the case, it was finally forwarded to New Delhi Special Task Force (STF) as Jammu branch was an Anti Corruption Bureau.

The investigations were entrusted to Investigating Officer, Inspector Ashok Kalra of New Delhi, STF on anti-terrorism. The survivors made the 192 km journey to reach Jammu to record their statements.

In November last year, when the family members had gone to Jammu to record their statements, Mohammad Afzal (Abdul Ahad’s brother) was hit from the back by a speeding motorcycle. He suffered serious injuries to his head and face, and had to be hospitalised for several weeks. He had to undergo surgery to reconstruct his fractured jaw bone, which he could not open for several months. He was deeply shaken and frightened and did not thereafter record his statement before the police.

Lately, one survivor was directly threatened by an SPO by saying: “Jo haal kiyaa thha, wahi haal kardenge.” (We will made you suffer like earlier). An altercation broke out, and a case was registered against the SPO for breach of peace (Section 107, RPC) on July 23, 2014. The High Court has ordered the CBI to file its ‘status report’ on the case by the August 18, 2014.

Some of the villagers of Sailan who abandoned their homes and livelihoods as a result of the massacre in 1998 have not returned. At present Sailan consists of about 600-700 scattered homesteads. In 1998, the SHRC reported the population of Sailan as 1888 persons.

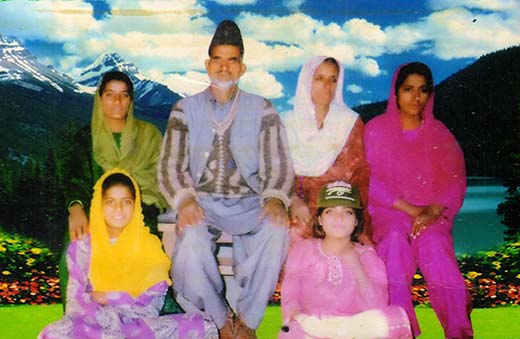

Abdul Ahad, whose father, mother, wife, two daughters, and two sons (aged 14, 10, 8, 7) and niece (10) were killed that night has remarried and has a new family. He works in the Sheep Husbandry Department. His eyes glaze, when he talks about that night, and his lost children. Shabir, now 35, was a high school student when the massacre occurred. He teaches in the Primary school located next door. He was married in 2004, and has three young children. Maqsood Sheikh, Imtiyaz’s brother, who lost six members of his family that night, and later his brother Imtiyaz, is also married and works as an electrician. The family members all speak bitterly with the anger and humiliation they feel at the sight of the perpetrators still roaming free.

“We are not safe yet,” Maqsood says. “Be it Army or Police, we continuously pass through their surveillance. Whenever we pass around, they [army and police] subject us though stares which only instils a sense of fear in us. But we are resolute enough and will never let the system to silence us!”