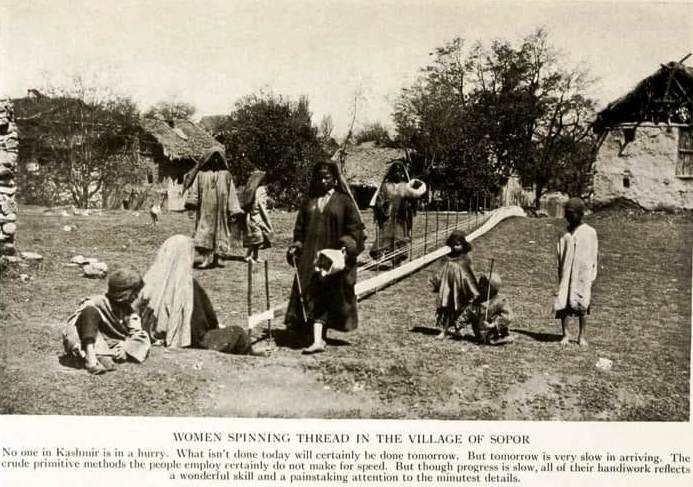

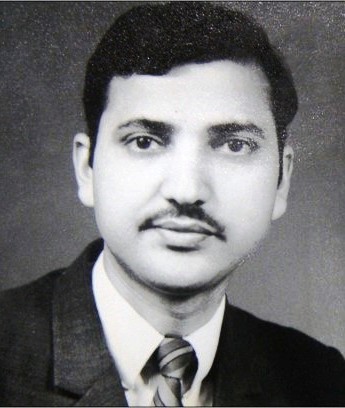

While offering the first-hand account of his birth and upbringing in Sopore, the ninth-century town, scientist and clinician, Dr M Sultan Khuroo details the life within and around the town and the struggles people put in to trigger a change for the good, steadily and surely

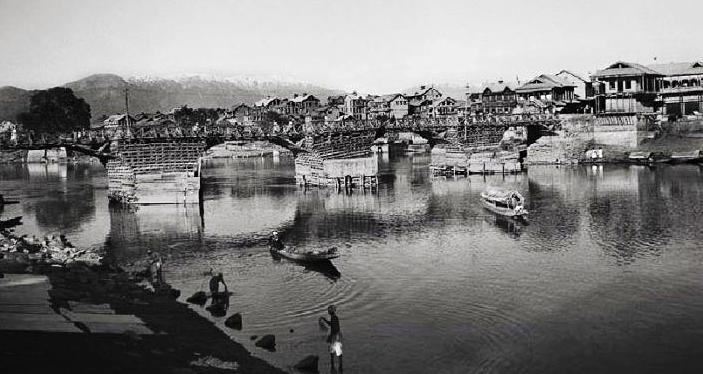

Sopore, my birthplace, is a Kashmir town, 45 km northwest of Srinagar. It is home to one of Asia’s largest fruit mandi (wholesale markets) and is also called the Apple town of Kashmir. Picturesquely located on the banks of Asia’s largest freshwater lake, the 24 x 10 km Wular, the town was founded by Suyya, who was an Utpala engineer and the irrigation minister of king Avantivarman (855-880 CE). While establishing the town from the river Jhelum basin, Suyya faced a deadlock as people avoided working on the project as they had to plunge into the gushing waters. So, he thought of a masterstroke and advised the King to throw half of his treasury into the river Jhelum, which he pleasantly agreed and ordered. To extract as many coins as possible, people plunged into the river and cleared the mud from the basin to search for coins. Through this ingenious design, Sopore town was built. The town was named Suyya-pur (Suyya’s place), which subsequently became Sopore.

Now, Sopore is a crowded busy business centre, a tehsil headquarters and a police district with almost 75,000 people living (2022). Well connected on all sides, it is accessed by Banihal – Baramulla rail link with a station at Amargarh, 2 km from the town. The population is diverse comprising traders, peasants, and fishermen.

Kraltengh: The Land of Potters

I was born at Mohalla Kraltengh (Kral means potter; tengh means knoll) situated in the heart of town. I belonged to an educated and respected Khuroo family. The Kraltengh hillock had clayey soil ideal for pottery and was inhabited by several potter families who made beautiful earthenware vessels. As a child, it was a great treat for me to watch them design their pots. These families, however, moved away from the area after the devastating 1957-Kashmir flood.

Our home was a five-storeyed house structured in red bricks and wood. All the floors had beautifully designed walnut Vuresi, sliding partitions, giving the family leverage to change over each floor from an open hall to many living rooms and vice versa. The fifth floor had a long and wide wood-roofed Dubb, an open-air gallery, veranda from which a beautiful view of the extensive willow forestry and Sopore waterways including Jhelum and distant Wular was a pleasure to watch. The ground floor kitchen housed multiple mud chulhas (clay stoves), fired by fuelwood. The traditional cooking provided burning coal for kangris used to fight during the cold.

Kangri is an earthen pot woven around with a wicker basket, filled with hot embers used by Kashmiris beneath their pheran, the long coaks. In fact, pheran and kangri continue to be the key instruments to manage chilly and harsh weather. The floor and walls of the house were made from clay to conserve heat. Gas cooking and central heating of house were a nonentity. We had Hammam on the ground floor that had stone flooring, which was heated by a furnace underneath. As the room would turn cosy, the family would spend most of the time in Hammam.

A four-story mud house constructed nearby was connected to the main building by a passage. Its ground floor had two stables one each for cows and a beautiful white-coloured horse. The roof was flat, could be approached from the fourth floor of the main building, and was exclusively covered with fertile soil meant for a terrace garden. The garden had exotic flowering plants, herbs like cumin and a specially organized saffron corner. However, the snow on a flat roof had to be regularly cleared during winters, an exercise by elders, I as a child would often love to join.

The housefront had a rose garden and a widely spread beautifully designed grape pergola. The pergola comprised four vertical pillars that supported cross-beams and a sturdy open lattice upon which woody vines grew and spread. The bewitching view of beautiful Kashmiri roses (Gulab, Phyllostachys Aurea) with fragrance and hanging grapes from the pergola lattice is yet vivid in my eyes. There was a large family vegetable farm by the side of the house, meant to grow cucumbers, tomatoes, potatoes, garlic, onions, peas, beans, and chillies. As a child, I loved operating Shaduf (toul in Kashmiri), which was erected to raise water from the stream for irrigation. It is a hand-operated device consisting of a pivoted pole with a bucket at one end and a counterpoise at the other end and works like a seesaw. An ancient innovation, Shaduf was used in India, Egypt, and some other countries for irrigating fields.

In front of the house, a wide deep fast-flowing waterway connected a large lake (named Bug) with Jhelum. Soon after returning from school, a swim in this waterway was my daily routine to kill the heat. On weekends and holidays, I would drive an oar-operated boat (Shikara) to reach Wular lake and enjoy swimming and fishing. The 2-km distance from my house to Wular was rich in flora and fauna. Extensive willow forestry on both banks of river Jhelum was inhabited by migratory and non-migratory birds and during my childhood, I often walked through this plant nursery to watch and appreciate nature at its best. This sight is not around now, unfortunately, as urbanisation has devoured it completely.

The Family Pedigree

The Khuroos are descendants of Prabat Khuroo, a devout Muslim who lived in fourteenth-century Kashmir. He is buried on the bank of river Jhelum at Chakroodi khan, adjacent to Sopore fruit mandi. Several generations of Khuroos’ over the centuries were headed by Prabat, followed by Dayam, Salaam, Rasool, Qadir, and Shaban. Khuroos’ in Kashmir have established several colonies in multiple locations which include Batangoo (Qaimoh, Kulgam), Guree (Bijbehara, Anantnag), Dal Lake (Srinagar), Ningli (Sopore, Baramulla), Kraltengh (Sopore, Baramulla) Seer-Jagir (Sopore, Baramulla) and Doabgah (Sopore, Baramulla).

Khuroos’ have traditionally been a trading community and for centuries, held the nerve of the supply chain especially food grains from Maraz (South Kashmir) to Kamraz (north Kashmir). Till the 1960s, much of the internal Kashmir trade depended upon navigation through the river Jhelum and Khuroos effectively supported and promoted it. Kashmir has a rare distinction that Jhelum was navigable for 163 km from Khanabal to Baramulla. In fact, there is no other instance other than Kashmir, situated at an altitude of 5000 ft above sea level, having a navigable river, intersecting it for so long a distance. It was said, “If Egypt is the gift of Nile, the Kashmir is the gift of Jhelum”.

My Extended Family

My family had established their permanent residence in Kraltengh in Sopore in the early part of the last century. Five sons (Gaffar, Fateh, Ramzan, Ismail, and Qadir) of Haji Mohammad Shaban Khuroo (sixth descendant in the family hierarchy) built five palatial houses adjacent to each other. They established lucrative businesses involving trade with food grains, timber trade, and the like.

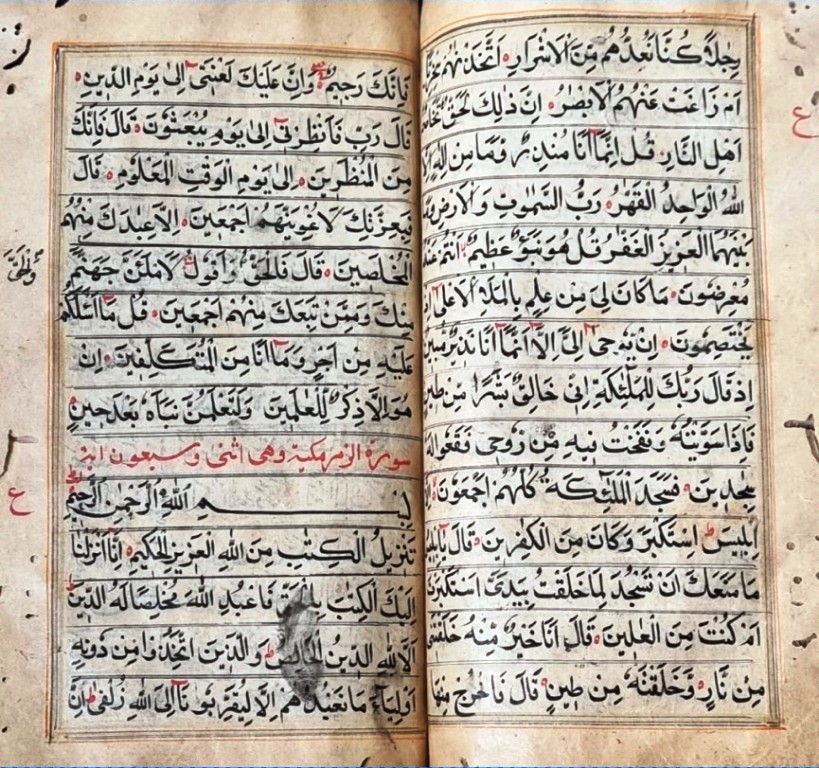

Family grandparent, Late Haji Fateh Khuroo (1885-1958) was a scholar in Persian literature. The Persian language is intertwined with the history of Kashmir and was the official language and a part of the school curriculum in Kashmir till 1947. Besides, Haji Fateh Joo, as he was popularly called, had studied Arabic and his Quranic recitation was so impressive as to amaze and immobilize the audience. As a child, I often visited him to silently listen to his recitation and discourse on religious and social matters of significance. During his life, he came in touch with many Islamic scholars and Sufi saints and his residence became a seat of learning. A 350-year-old handwritten version of the Quran on a Burza paper available with the Khuroo family is a great religious antique and a visual delight.

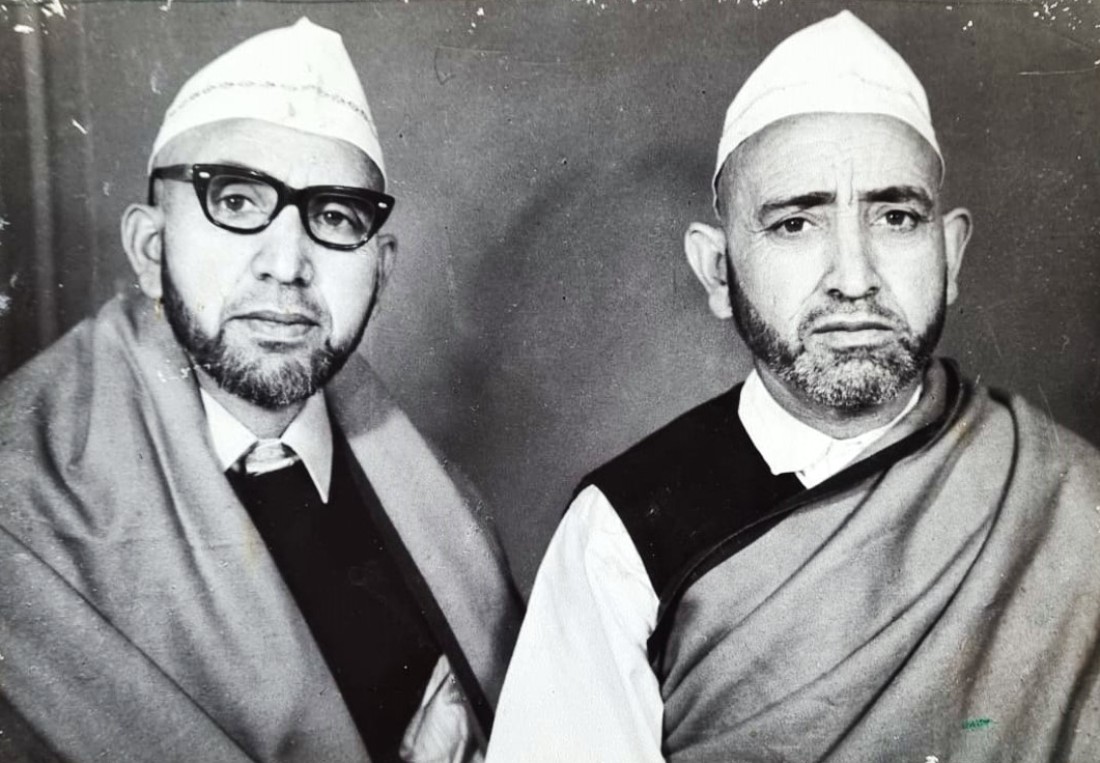

Haji Fateh Khuroo had seven siblings, five sons, and two daughters. My father (Haji Abdul Rahim Khuroo) was one of the seven (third in order) siblings and was adopted by his uncle Haji Mohammad Ramzan Khuroo. Late Haji Abdul Rahim Khuroo (1922-1995, my father) and Late Haji Abdul Khaliq Khuroo (1918-1981, my uncle) were educated in the Persian language. Both brothers were running a successful business. They supported many NGOs working in far-flung regions for orphans and widows. They promoted Islamic teaching and culture in society. Because of their wisdom, they earned special respect and status in society and were frequently approached for support, solutions, and advice. They would find amicable solutions to contentious issues in families.

Haji Abdul Rahim, my father actively involved himself in many social organizations, especially Anjuman-Moinul-Islam Sopore, a religious and educational body registered in 1972. The Anjuman had established many schools and colleges in the town at that time, which did commendable service in promoting scientific and religious education.

Nostalgic Childhood

The excellent love and care from my mother, my grandmother, and my aunt made me feel strong and confident. I was in close touch with my father and uncle and received excellent advice about how to stay focused, face the vagaries of life, and do work with honesty, dedication, and empathy. I attribute my successes in life to my parents and the family members, who guided me at every step in my career to do the right.

I remember one unusual event of my childhood. In the middle of the night, I had been observed on multiple occasions to leave the bed, open the bolted doors, come down and out of my house and walk along the bank of the waterway in front of the house and return to the bed. The family once noticed me sitting on a porch (a covered shelter projecting in front of the entrance of a building) which had been constructed to hold (and cool) an earthen water container on the fifth floor. It was somnambulism, the sleepwalking.

To prevent me from sleepwalking and consequent accidents, my uncle had devised an ingenious plan to tie a thin rope to my right toe, which would wake me up while I attempted to start night walking. Fortunately, over time I could come over this habit. As of today, I disagree with the management but accepted treatment protocols namely cognitive behavioural therapy, benzodiazepines, and melatonin were non-existent at that time.

My School Days

I did my primary schooling at Government Boys School, Baba Yousuf. It was a Jabri School established by Maharaja Hari Singh to enforce education among the general population. Housed in a dilapidated four-story building, it would shake violently when the Sopore-Bandipora passenger bus passed on the adjacent road twice a day. There, I actively participated in the Naya Kashmir (New Kashmir) programme, an immensely popular public movement, with a blueprint for a welfare state notable for a humanistic view of development. Under the guidance of teachers, I visited extensively to adjacent villages and towns and made public utterances on several social issues like the value of education, rights of women and girl-child, antenatal care, personal hygiene and other things.

I did my high schooling (ninth and tenth grade) at Government Boys High School, Sopore. That era witnessed several administrative changes leading to progress as Naya Kashmir started being implemented. One such programme started by the Government in educational institutions was Jashn-I-Kashmir. It intended to bring to light many aspects of Kashmiri culture and served as a vehicle of contact between Kashmir and the rest of India. It showcased regional theatre, music, poetry, and dance of Kashmir as well as of various other states. The students would actively participate in this programme.

In the fifties, the ultimate goal for attaining excellence in education was to pass matriculation, the examination of which was then conducted by the University of Jammu and Kashmir. I remember when my cousin passed his matriculation examination, he was amongst the few who had attained this distinction. As it would happen, the occasion was celebrated in the community in a typical Kashmiri customary style. He was dressed like a bridegroom, placed in a decorated horse-driven buggy, and carried to the most important landmarks of the town including khanqahs of Sufi saints.

Ladies followed the buggy on foot singing Kashmiri folk songs with the theme “I am a Matric Pass”. I completed matriculation a few years later and had the distinction of standing high in merit in the University. It did excite celebrations but not with the same fervour as for my cousin who had completed matric a decade earlier.

In High School, I was a victim of considerable verbal trolls from several backbenchers. It was a reaction to my scores in examinations or good comments passed by my teachers during quizzes. Trolls were about physical appearance, dress, friends, and family and sometimes involved physical abuse as well. I dealt with this crisis with patience and endurance and did not allow it to come in the way of my career. Having experienced and dealt with trolls in childhood, I effectively managed the trolls and cyber-bullying later, launched mostly by some urbanites towards my suburban birth.

I completed FSC (eleventh and twelfth grade) from Government Degree College Sopore. I had a personal liking for Mathematics in addition to science and filled out the registration form for non-medical subjects. However, as luck would have, one senior professor who was receiving the forms on the college lawn advised me to take medical subjects (English, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Urdu as optional) and edited the registration form accordingly.

During this period, I was guided by many stalwarts who taught me discipline and mannerisms. I passed my FSC, obtained the first position in the district, and was a position holder at the University of Jammu and Kashmir. This made me eligible to get into the Government Medical College Srinagar for MBBS and thus ended my intimate attachment with Sopore.

Social Order of That Era

Over the decades’ several fundamental changes had occurred in Kashmir’s social order. These were triggered by improved socioeconomic and educational status of society, administrative orders, changing perceptions, and a shift from one-man rule to democracy. I was born when the Princely State was ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh. During the 101-year-long Dogra rule, the Kashmir peasantry worked as serfs for absentee landlords, with consequent socio-economic impact. In addition, natural calamities like famines, floods, epidemics, earthquakes, and fires resulted in human miseries and enormous loss of life.

During my infancy, several political upheavals occurred in the region. These included the Quit Kashmir Movement (1946), Tribal Invasion (1947), First Indo-Pak war (1947-48), Naya Kashmir movement (1948-1953) that eventually led to the termination of the Jagirdari system, and the imprisonment of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah (1953) and takeover of governance by Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad. To ward off the dangerous effects of these frequent political upheavals, many families including ours had established an alternative residence in a houseboat placed in the middle of the Wular Lake, used it for several years, and would shift to and fro whenever needed for safety.

I witnessed several calamities during the sixties that took a heavy toll on Kashmir. The massive flood of August-September 1957, devastated Sopore. It was followed by a drought (1958) that left a large population rendered homeless by floods, penniless and hungry. Schools reported massive dropouts. My family fought this calamity with hard work and dignity. I did my part and housed myself in a makeshift room and ran a small parallel business, and extended tuition facilities to other fellow students in the community to generate small money to sustain my education.

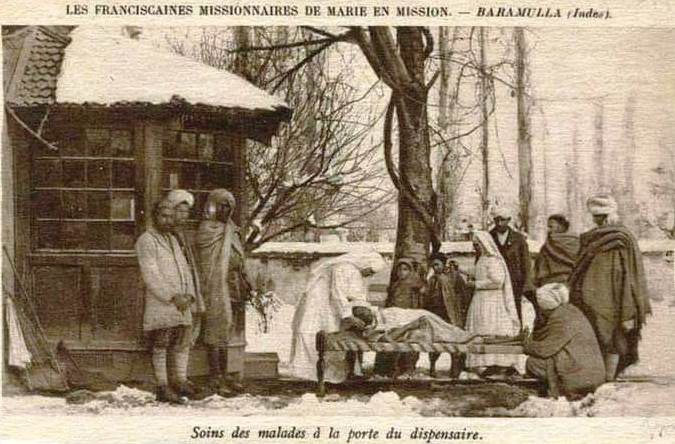

The Healthcare

The healthcare in that era was focused on the Hippocrates Tibb as allopathy (modern medicine) was non-existent. Unani medicine, along with herbal treatment was adopted and practised at its best. Unani medicine, as the name implies, was established in Greece by the great physician and philosopher, Hippocrates (460-377 BC). It subsequently spread to Egypt, Persia, and the Arabian Peninsula and was introduced in India around 1350 AD. India has had many great Unani physicians (Hakims), of whom Hakim Ajmal Khan’s (1864-1927) stands tall. In Unani Tibb, disease diagnosis is done by examining the patient’s pulse and observing the patient’s appearance. Treatment revolves around herbal medicines, massage, hammam (bath and sauna), vomiting, purging, cupping, leeching, and a special diet.

During my childhood, most elders knew the name of the herbs meant to treat common ailments and I often would procure them from Guppa-Bohar, a resource shop, located in the main market outside Jamia Masjid. The children in that era were often infected with roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides) and as it would, this highly motile parasite would explore every human orifice, maybe eyes, ears, nose, mouth, umbilicus, and of course anorectum. Parents would deworm children once or twice a season with a decoction of a herb called Tethwan (Wormwood, Artemisia).

The experience of drinking this decoction was a very unpleasant experience, hated by one and all. The practice of bath and sauna in Hamams, however, was popular, especially among ladies after childbirth. The practice of leeching to purify the blood, help wound healing, and relieve the pain was another popular remedy. The obstetrical services were offered by elderly respectable women in the community who had gained such experience by practice without formal training. Obstetrical services for our family were provided by a missionary Midwife, Mrs Fazal Bibi, who had established a dispensary with a Labour room in the Mis Bagh (Mis means nurse; Bagh garden) on the town outskirts. She conducted deliveries both in the hospital and at home. She was pleasantly attached to womenfolk and would give them a lot of social and emotional support.

The Tanga Town

Sopore’s transport services have always been exceptional. It TangaTown. I have seen Tangas on Sopore roads as the main and sometimes exclusive mode of transport. A tonga or tanga is a horse-driven light carriage or curricle. It has a canopy over the carriage with a single pair of large wheels. The passengers reach the seats from the rear while the driver sits in front of the carriage. Some space is available for baggage below the carriage, between the wheels. This space is often used to carry hay for the horses.

I remember a few Tangawalla’s (tanga drivers) who loved this profession and would decorate the horses, the canopy, and the wheels. It was great fun to have a ride in such carriages, though a bit costly. While Sopore has maintained the time-old Tanga tradition, the only place I can locate one in Srinagar is when I visit Hotel Grand Lalit, where a decorated Phaeton (carriage) is waiting to give you a ride on the parking way.

During my student days, places adjacent to Sopore were reached either on foot or in Tanga. However, it was hard to cover a distance of 30 miles to reach Srinagar by Tanga, though some veteran Tangawalla would try it occasionally. So, this expeditious distance had to be covered by one bus trip per day. A 25-seater minibus would be parked in Sopore Bazar and would call for passengers to Srinagar. It would only start its journey once all the seats were occupied and this process would take hours. On some days the seat occupancy would not get full by late afternoon or evening and the driver would advise passengers to return the next morning for the Srinagar journey. People were relaxed and would happily agree to this arrangement of making the Srinagar ‘expedition’.

Calendar and Coins

Those days the popular calendar in vogue, especially for business purposes was the Vikrami which is 57 years ahead of the Gregorian calendar. My date of birth recorded in family records was in the Vikrami calendar. The Gregorian calendar had been adopted for official and educational purposes in India on March 22, 1957. However, it took several years before we shed the Vikrami calendar.

The currency was in rupees with currency notes from Rs 1, 5, 10, and 100. The rupee was divided into 16 annas and 64 paise. Well-designed coins of Bronze, Copper, and Nickel were meant for various denominations of Anna and Paisa. I was very proficient in using these coins. In the morning I was given 2 annas to buy Kashmiri bread from the baker’s shop and 6 annas to buy one paw (250 g) of mutton. On Eid, I would be excited to receive two paise as eidhi.

The move toward decimalization was being frequently discussed, however, the amended Coinage Act came into force on April 1, 1957. The rupee remained unchanged in value and nomenclature. It, however, was now divided into 100 paisa instead of 16 annas or 64 paise. For public recognition, the new decimal Paisa was renamed Naya Paisa till June 1, 1964, when the coin shed prefix Naya.

Mass Media

That era belonged to the radio and cinema as sources of information, education, and entertainment. Some of the new announcers were legendary and BBC radio news was highly rated, listened and sought. Sopore had the distinction of having Samad Talkies, which procured and telecast great Bollywood films. Many of us would silently slip into the front row (third class) after paying six annas and watch the film.

I recollect watching great films like Awara, Baiju Bawara, Daag, Do Baiga Zamin, Aaah, Amar, Boot Polish, Devdas, Shree 420, and Naya Daur to name a few. Each film had a message and these cinema-driven messages left a deep impact on the social setup. The songs and the music were of excellent quality and impressive for the young generation.

Festivals

Festivals in Sopore were celebrated with great interest, fervour, and involvement. Eid was a special occasion to visit and socialize with neighbours and relatives. Children would enjoy playing and socializing with friends and return home late at night, only after the family would start looking for them. Dussehra was a source of great attraction and all of us would assemble on college ground to watch the burning of effigies of Ravana, Kumbhakarna, and Meghanada.

One distinctive feature of Sopore was the highly coordinated and disciplined use of Charas in society. Charas is a cannabis concentrate made from the resin of a live cannabis plant (Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica) and its use can make one feel relaxed and may lead to hallucinations.

A dedicated Charas Centre called Charas-Pindh had been created in the heart of Sopore town where the Charsi’s (charas addicts) would visit in the evening and smoke charas in Chillums and enjoy the fag and listen to sofiana music.

Then, Charas use was legal and there were no drug addicts in society. Charas was made illegal in India under pressure from the United States in 1985 and trafficking of charas was prohibited by the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (NDPS), 1985.

Conclusion

A lot of water has flown down the Jhelum since then. Sopore saw an economic boom in the fruit industry. This led to improvement in infrastructure, socio-economic parameters, educational institutions, and political awareness. Over the years, Sopore gave birth to many legendary personalities across all spheres of life. Some of them are part of history. Long Live Sopore.

Post Script

The author wants to acknowledge the efforts that several of his family members including his brothers (Haji Mohammad Ismail Khuroo and Haji Rafiq Ahmad Khuroo), cousin (Late Haji Mohammad Ramzan Khuroo) and nephews (Hafiz, Imran and Junaid) made by travelling extensively to explore and document the pedigree of the Khuroo family. He is

personally indebted to (Late) Mohammad Amin Shakib and Jenab Mohammad Yousuf Taing for their opinion on the hand-written copy of Al-Quran that is with the family.

(Leading gastroenterologist, Dr Khuroo is a scientist, who headed SKIMS earlier.)