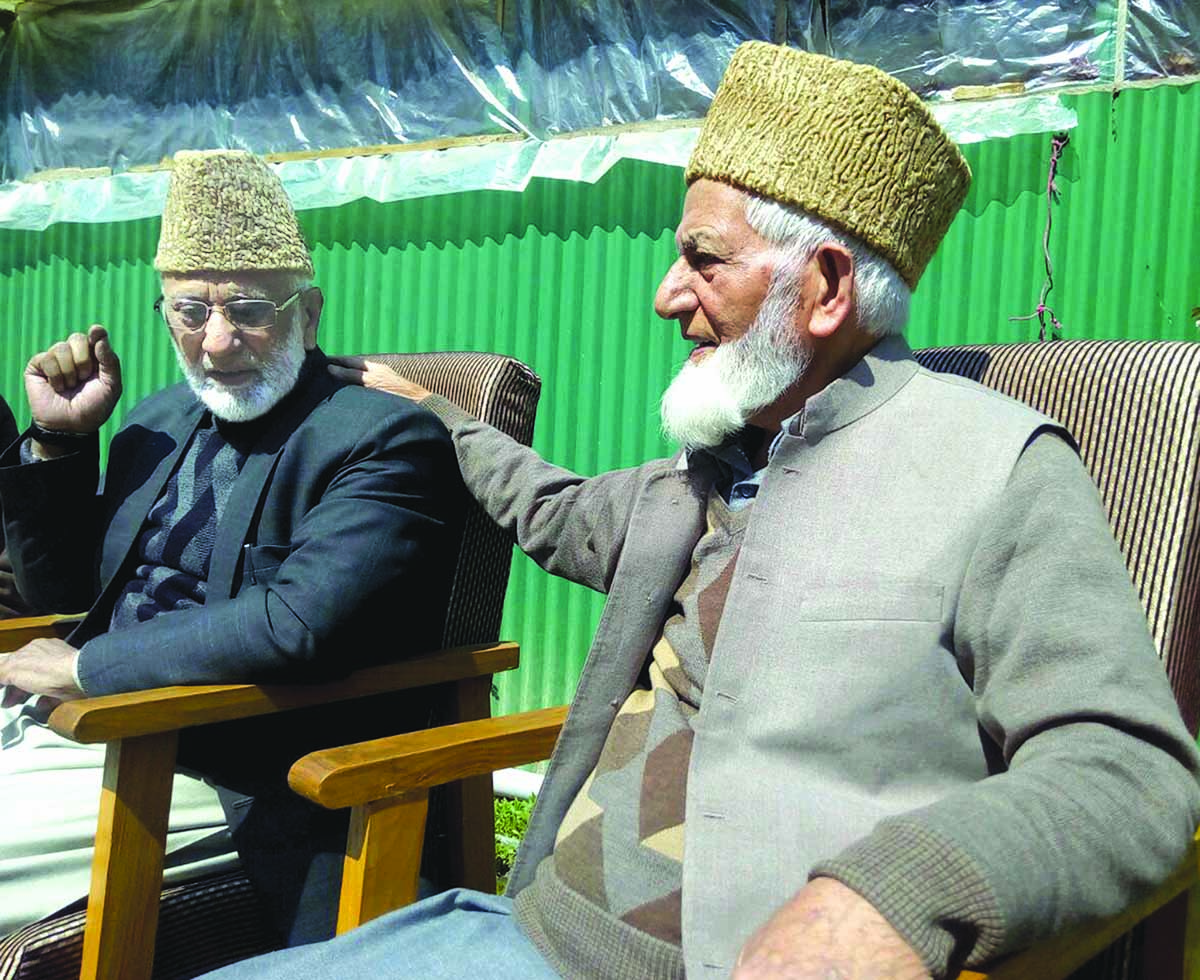

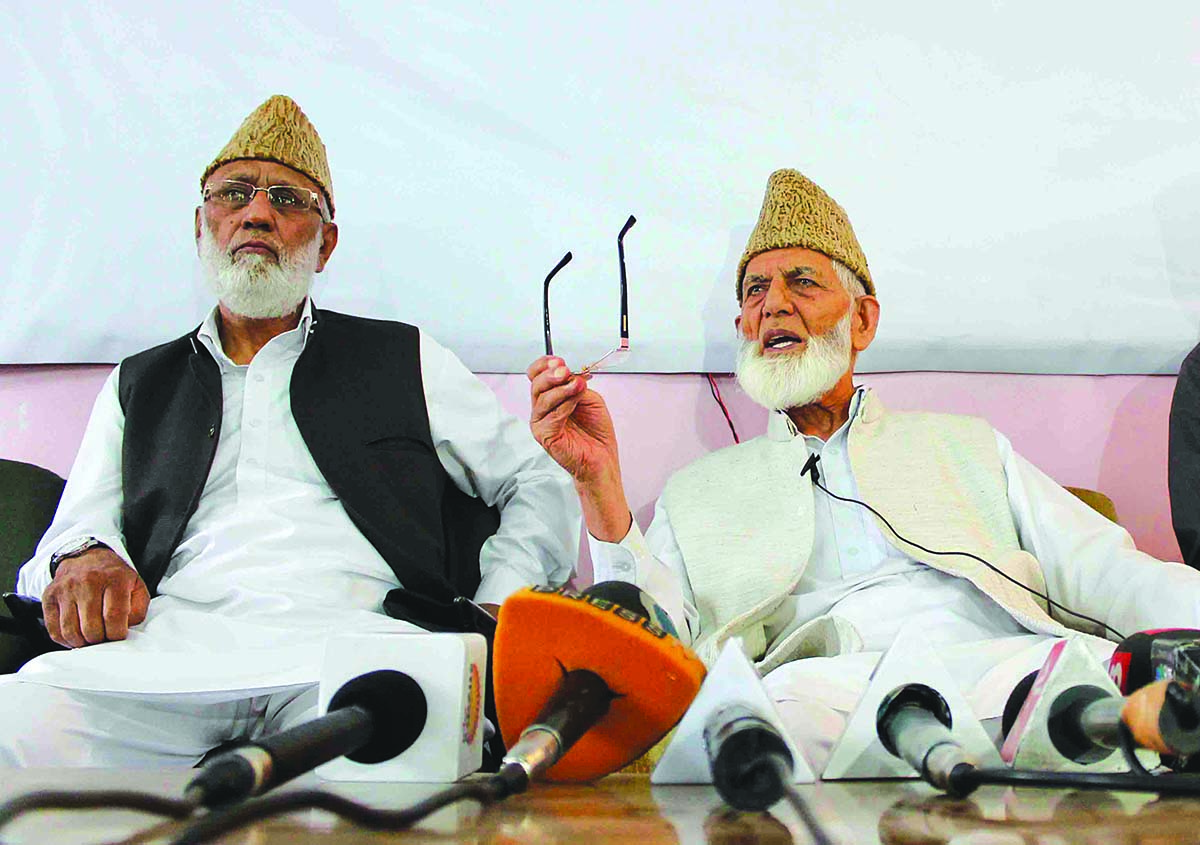

With a frail Syed Ali Geelani passing the baton of his party to his longtime friend and follower Ashraf Sehrai, the talk in the troubled town is who this new man is. Shams Irfan meets both the separatists to create a narrative of their association spanning Kashmir’s last seven decades

Almost five hours after Mohammad Ashraf Khan alias Sehrai, replaced Syed Ali Geelani as chairman of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat, his house in uptown Baghat locality of Srinagar, wore a deserted look. The only visible sign of life in his sprawling house, located in a narrow alley, was from a lone lamp glowing inside a first-floor room. Rest of the house, including the spacious lawn, was completely dark. The main entrance, guarded by two black iron gates, was bolted from inside. One had to literally kick the door, till one traces a small doorbell hidden in a corner, to seek the attention of the inmates. Interestingly, on this day, there were no sleuths in plain clothes loitering outside, pretending to be neighbours.

Once inside, the longtime aide of Geelani and man of the moment, Sehrai shows up and quickly settles himself in a corner of his drawing room. Unmindful of the euphoria surrounding his elevation, Sehrai looks lost in his thoughts.

Five minutes later, a guest, after exchanging greetings, asks him rather directly: how challenging is the elevation? The question follows a long pause engulfed by complete silence. “The biggest challenge is to survive here,” said Sehrai, looking thoughtfully at his guests face.

Sehrai’s journey from nondescript Takipora village in picturesque Lolab valley, to posh uptown Hyderpora’s Tehreek-e-Hurriyat office in Srinagar, is dotted with life-changing events, spanning over six decades. But where and how did it all start?

In 1949, then five, Sehrai’s two elder brothers joined Jamaat-e-Islami as its basic members and started visiting organization’s district office in Kupwara. There they came in contact with Jamat’s district head (Amir-e-Zila), a young orator with extraordinary motivational skills. He was Syed Ali Geelani. Whenever Geelani would visit Lolab, where he had relatives, he used to visit Sehrai’s house as well to meet his newly christened Jamati brothers.

“I started visiting his (Sehrai’s) house for my party-related works. That is how we met,” recalls Geelani, two days after he handed over reigns of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat to Sehrai.

With no road connectivity with Kupwara town then, one had to walk his way through mountains into Lolab valley’s Tekipora village, a godforsaken place in those days. “I would often stay at his home for a few days whenever in Lolab,” recalls Geelani.

Initially, Geelani’s visits to Tekipora and other parts of Lolab valley used to be for the propagation of Jamat’s ideology. “But, later I also used to visit for sake of my bonding with Sehrai’s family,” recalls Geelani.

After Sehrai appeared in his class 10 examination, Geelani came to his house and asked him to teach at a Jamat run seminary in Sopore till his results are out. “I was not sure if I could teach as I was too young,” recalls Sehrai. “But he (Geelani) succeeded in convincing me and my brothers.”

Before Sherai left for Sopore to formally join Jamat’s Darsgah, the seminary, his widowed mother took Geelani aside and said: Yih haz chuie hawal (I am putting him in your custody). “Since that day he is with me as my friend and companion,” said Geelani, with a smile on his face.

First Jail

In December 1963, Kashmir was literally on the edge after the mysterious disappearance of Moh-e-Muqaddas (holy relic) from Hazratbal shrine. Within days it created a storm of sorts as around fifty thousand people, carrying black flags marched towards the shrine. To press the government for the relic’s recovery, Mirwaiz Mohammad Farooq formed Moh-e-Muqadas Majlis-e-Amal, an amalgam of different parties including Jamat-e-Islami, Jamiat-e-Ahlehadees and other religious parties. At first, their aim was to ensure the return of the holy relic, but once it was returned in January 1964, a part of the amalgam started supporting Sheikh Abdullah’s boycott call against Congress in Kashmir. “The boycott call was so effective that local Congressmen couldn’t even move out of their homes,” recalls Sehrai. “When Mir Qasim’s mother died, almost nobody attended her funeral.”

Enraged by the support Sheikh Abdullah received from different quarters, Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq, the then Prime Minister of Kashmir, ordered the arrest of all people supporting the boycott. “Immediately police started arresting people associated with Moh-e-Muqadas Majlis-e-Amal,” said Sehrai. As Jamat was part of the amalgam, its cadres too were arrested. “I clearly remember the first phase of arrests started on January 26, 1965,” said Sehrai.

A teacher at a Jamat-run school in Baramulla then, Sehrai received a letter from Jamat’s Srinagar office instructing him to speak against the arrests during Friday prayers. “After I offered prayers at Pattan mosque, I gave a strong speech against the arrests,” recalls Sehrai.

Amid applauds, Sehrai said, ‘what kind of democracy cages free speech and people who speak the truth.’

The same day, at around midnight, a loud knock at the landlord’s door, where Sehrai was putting up in Baramulla, woke everyone inside the house. “Two Jamat members from the local seminary came with the news that police is looking for me,” recalls Sehrai. “They told me that my speech at Pattan has enraged people in power in Srinagar.”

The next day, in order to save his landlord, who had small kids, from further inconvenience, Sehrai decided to stay for the night at a local Jamat run school. At 11 pm, a knock at the school door alerted Sehrai. “I still remember the date. It was March 13, 1965,” said Sehrai. “The police party was lead by an SHO named Sadruddin. He was looking for headmaster who delivered a speech at Pattan.”

That night Sehrai spent at Baramulla police station. The next day, at around 4:30 pm, SHO came and said, “Get ready. We are taking you to Srinagar.”

At 9 pm, Sehrai was finally inside the Central Jail Srinagar. By the time he reached there, the dinner was already over in jail. “I was kept in Cell No 19, meant for Sangeen (critical) prisoners,” recalls Sehrai.

With no hope of receiving any food, Sehrai decided to offer prayers he had missed during travel. “As I started praying an earthquake struck. There was hue and cry inside the jail. People were crying for help but nobody came,” recalls Sehrai. “After I finished prayers, I got up and stayed close to the iron gate.”

Once the order was restored inside the prison, a person named Gul Saleh, who was serving a life sentence in a murder case, came and gave Sehrai some food and candles. “I ate the stale food and tried to sleep. I knew my first night in jail was going to be a long and memorable one.”

The next morning Sehrai came to know that in Cell No 18, there were more people from Sopore. “They were Mahaz-e-Raishumari activists,” recalls Sehrai.

On the third day Jail Superintendent, a Lal Bazar resident named Qureshi, came to visit the jail. After inspection of cell, he ordered the jailer to put Sehrai in a special cell. “I took my belongings and went to that place,” said Sehrai.

For the next twenty months, Srinagar’s Central Jail became Sehrai’s permanent address. This is where he was about to get a new identity. An identity that would define him and help him survive the changing political fortunes of Kashmir.

Together In Jail

After Sheikh Abdullah gave call for social boycott of Congress workers and its sympathisers in Kashmir, he proceeded on Hajj, the Mecca pilgrimage, with his wife and friend Afzal Beigh. From there he went to Egypt, England, and Algeria, and also met Chu-zu-Lai, the first premier of the Peoples Republic of Chinese. This enraged Delhi as Chu-zu-lai had invited Sheikh Abdullah to China, apparently on the behest of Pakistan. On May 8, 1965, after Sheikh Abdullah landed in Delhi, his passport was seized and he was arrested and sent to Ootacamund Jail. “Given his popularity, his arrest in Delhi led to widespread protests across Kashmir,” recalls Sehrai. “Many protestors died in police action. I remember five people were killed in Sonawari area alone.”

As protests spiraled out of control G M Sadiq, who was now reduced to Chief Minister instead of his original title of Wazeer-e-Aazum or Prime Minister, ordered the arrest of all political and social activists including Jamat-e-Islami cadre. This second wave of arrests brought Geelani to Central Jail, where Sehrai was already lodged. “He was arrested on the same night as Sheikh Abdullah,” said Sehrai. “We were finally together again.”

The next six months Geelani and Sehrai spent together inside the Central Jail Srinagar cemented their bond, and created a lifelong camaraderie.

Khan to Sehrai

At 21, when Sehrai first stepped inside the Central Jail Srinagar, he had no idea he would be kept for such a long time. “I had just packed a few clothes when I was arrested,” recalls Sehrai. “But my main companion inside were my books.”

One book in particular that influenced Sehrai during his early years of incarceration was Zar-e-Gul by Pakistani author Kausar Niazi. “I had bought this book from Baramulla. And with ample free time in jail I had almost memorised it,” recalls Sehrai.

Influenced by its poetic narration style, once Sehrai finished reading the book, he took a pen and inscribed on its last page: Sehrai. “I wrote it without any particular purpose. It was just a way of expressing myself,” recalls Sehrai.

Sehrai, which loosely translates into someone who is a wanderer. Or someone whose life is full of struggles, was soon going to become Mohammad Ashraf Khan’s permanent identity.

A few days later, Shah Wali Mohammad, a teacher from Sopore who once taught Sehrai, and was jailed for his affiliation with Jamat, visited Sehrai’s prison cell as per routine. During the conversation, he started flipping through the pages of Zar-e-Gul. He stopped at the end of the book and read Sehrai word loudly and asked: is this your nom de plume (pen name). “He then went to Geelani and told him that Mohammad Ashraf Khan is now Sehrai.”

First Speech

Once out of prison (Sehrai in November 1966; Geelani and Moulana Saaduddin in March 1967), Jamat-e-Islami started picking up threads of its existence. In order to reaffirm its carder that everything is hunky-dory and Jamat stands firm, both in resolve and ideology, a large ijtemah (congregation or seminar) was organized in Srinagar’s Batamaloo. It was decided that during the seminar Jamat will bring resolutions on certain key issues concerning Kashmir. And each resolution will follow a talk on it by an expert for fifteen minutes. Sehrai was asked to talk about the Kashmir issue after a resolution is presented. “I was too young to talk on such a sensitive issue,” recalls Sehrai. “So, I refused and proposed Geelani’s name instead. But they didn’t listen and said you have to do it at any cost.”

A shy young man who was hesitant to speak in front of elders finally talked about the Kashmir issue for fifteen minutes, leaving everyone in the audience spellbound by his oratory skills. “When I was called on the stage, Geelani Sahab introduced me as Sehrai. Afterwards, everyone knew me by this name only,” recalls Sehrai. “In a way it is Geelani who created my identity, both then and now.”

Safa-e-Pakistan

Later that year Geelani, who was the editor of Jamat’s mouthpiece Azaan, a monthly magazine, asked Sehrai to gather views from first-time participants at the Batamaloo seminar. Sehrai talked to a number of people, collected their views in a single article, and started it with a couplet: Ek walwala i taza diya mainey dilon ko (I have given new enthusiasm to hearts). This article was liked by everyone especially Geelani, who asked him to continue writing for Azaan.

In 1969, Sehrai started publishing a monthly magazine titled Tuluv (sunrise), from Sopore on behalf of the local Jamat office.

Apart from the editorial which Geelani used to write, everything from commissioning of articles, designing, printing, and writing a dedicated column about happenings in Pakistan titled Safa-e-Pakistan was done by Sehrai. “My column was about political and social developments in Pakistan,” recalls Sehrai. “It was widely read and appreciated.”

Within a year of its publication, Tuluv started getting letters and submissions from as far as South Africa. But in late 1970, Tuluv stopped publication after it ran into trouble with local socialists for calling Pakistani poet Allama Iqbal a non-socialist personality. “It was a huge controversy that saw G M Sadiq backed socialists writing against us,” recalls Sehrai.

For the next few months, Sehrai and Geelani wrote long columns in defence of Tuluv’s special issue, which they had dedicated to Allama Iqbal a few months back. Their job was to defend both Jamat and Tuluv and counter socialist’s propaganda.

Their main target was Ghulam Nabi Khayal, who had written long pieces in monthly Chinar, trying to expose Jamat, and its “false” claim over Allama Iqbal. Also, Geelani and Sehrai targeted a woman writer named Ashia Bhat. “It was a fake name that local socialists had created to criticize Jamat and its cadre in various publications,” claimed Sehrai.

When the controversy refused to die down even after six months of writing articles and counter articles, Sehrai wrote a postcard to Deoband-based Maulana Amir, explaining his situation. “He wrote an article in the next issue of Tuluv in which he criticized Ashia Bhat and others. It was a hard-hitting article but sadly it failed to keep socialists quiet,” recalls Sehrai.

As “Iqbal controversy” kept Sehrai busy most of the time, a few Jamat workers in Baramulla felt alienated. They started lobbying against Tuluv saying it keeps Sehrai away from other party-related works. “That was not true. I used to manage both things finely,” said Sehrai. “But they didn’t listen. And finally, in 1971, Tuluv was closed.”

A few months before Tuluv stopped publication Sehrai and others were jailed once again.

Passing It On

On March 19, 2018, after almost seven decades of friendship, a frail but resolute Geelani passed on the charge of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat to Sehrai, during a small ceremony held inside his Hyderpora residence, where he remains under detention since 2010. “I still recall his mother’s words: Yi haz chuie hawaal (I put him in your custody),” said Geelani with a smile on his face.

But taking the reign of Tehreek-e-Hurriyat, one of the most powerful separatist camps, in post-Burhan Kashmir is like walking on the razor’s edge. “He faces a very tough situation given the circumstance prevailing in Kashmir. The foremost being the rise of alternative narratives like ISIS and Al Qaida,” said Geelani. “It is a very dangerous situation.”

But Geelani is confident that Sehrai’s experience and political acumen, and a long illustrious life full of hardships, will come in handy in facing any situation. “I am sure he will prove to be an able leader if he is supported by the Tehreek-e-Hurriyat cadre,” said Geelani.

However, both Geelani and Sehrai know that countering alternative narratives and politics of flags, which have emerged in the past few years and gained some support among a section of youth, is not an easy job. “This challenge comes from within and not from outside. That is why it is more dangerous,” feels Geelani.

But with less than a week in Kashmir’s most powerful chair, Sehrai has already made his intent clear. “We won’t remain mute spectators,” he tells a small audience sitting inside his tiny office at Hyderpora.