Ocean of Tears is the first government funded documentary on Kashmir’s human rights crisis. In anticipation of its maiden screening,120000 people watched it. Shams Irfan meets the filmmaker to delve into the remaking of some of the darkest chapters in our contemporary history.

With one lakh plus hits on Youtube in just 15 days, an excerpt of Ocean of Tears (OOT), a documentary on the suffering of women living in a conflict obliterated state by an independent filmmaker Bilal A Jan, has become an internet sensation.

OOT is not the first documentary made on Kashmir. Ezra Mir made the first short feature film in Kashmiri titled Pamposh in 1952. The film was inaugurated by then Prime Minister of Kashmir, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and shot on the banks of the Dal Lake. The film was screened at the Cannes film festival but its print has been lost.

After Ezra, many Mumbai based directors made films like Menzraat, Mahjoor. Prabhat Mukherjee made biographical drama title Shayar-e-Kashmir Mahjoor on Kashmiri poet Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor’s life.

OOT has an edge over these movies because it talks about issues which are controversial in nature and have been either ignored or talked in mainstream media and cinema in whispers.

Funded by the Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT), a non government organization financed by the union ministry of information and broadcasting, the 27-minute-long documentary talks about the violence carried out against women in conflict torn Kashmir allegedly by Indian security forces.

Bilal has managed to raise a few uncomfortable questions in his film which, so far, have been neglected by the mainstream Indian media. He talks about Kunan Poshpora, the infamous village in north Kashmir’s Kupwara district, where more than 53 women were allegedly raped by the Indian army during search operations in February 1991.

Hailing from Sringar’s Chatarbal area, Bilal left for Mumbai after completing his graduation from Kashmir University. “I stayed there for four years during which I struggled as a filmmaker,” he said, “No doubt, the struggle has not ended yet,” he added quickly with a smiling face.

Like most youth of his age, choosing a career was never an issue for Bilal. All he had to worry about was how he would survive in a place like Mumbai where living costs are high. Throughout his stay in Mumbai, Bilal did odd jobs like teaching kids and working as a marketing manager to keep his dream of filmmaking alive.

Bilal’s luck changed when he came in contact with famous Bollywood filmmaker, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, during a film appreciation course at FTII Pune. Vidhu offered him an apprenticeship and made him an assistant director for his upcoming romantic thriller, Mission Kashmir. “Working with Vidhu on Mission Kashmir was my first formal training as a filmmaker,” Bilal recalls.

After Mission Kashmir, Bilal worked briefly as a programme consultant for newly launched Urdu television network by Zee Telefilms, Mumbai. “I consider this period as part of my struggle in Mumbai,” he said. The box-office success of Mission Kashmir gave Bilal hope that his association with the film would be recognized and rewarded soon. Bilal was confident of getting another chance to work with a biggie in Bollywood before he would independently venture into filmmaking. Shyam Benegal’s film, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2005) was announced and Bilal got an opportunity to assist him. “Assisting Shyam Benegal was like being in a filmmaking school,” he feels.

Bilal recalls that since his childhood days, he liked art movies rather than the popular commercial cinema. “I am inspired by Satyajit Ray,” he said. “I was never comfortable with commercial movies. After Mission Kashmir, I got an offer for a very low budget film. It was purely a formula based film. But I refused the offer. Maybe I could have taken the offer if it was an art film.”

Bilal took it as a cue to start his own work and headed straight back to Kashmir. The reason he came back was that the projects he was associated with in Mumbai got delayed endlessly. “I wanted to make a feature film on Kashmir about its culture and language. I could not have waited forever for another chance to come my way. Actually I wanted to make my first documentary on Kashmir issue but my financer was not comfortable with conflict as subject. He didn’t want to take risk with a controversial subject,” said Bilal.

Once back in Kashmir, Bilal immediately started working on a story and sent it to Soni Tarapur Wala, an Indo-American scriptwriter, for consultation. “She liked the story but said that it has many loose ends and needs to be tightened to make it into a feature film,” he said. “Unfortunately, I could not make it into feature film. I am still working on it.”

Things did not turn the way Bilal expected when he decided to shift his base to Kashmir. Though Bilal made a few documentaries for DD Kashir on career and educational development, but the artist inside him craved for more to satisfy his creative genius.

Bilal got a chance to work on a five minute short film for Take One and Zee Kashmir titled Harisa – The Winter Dish in 2006.

That was also the initiating point for The Lost Childhood (TLC), a 32 minutes long documentary about child labour in Kashmir.

“Harisa – The Winter Dish was liked by Zahid Manzoor (the then head of Take One TV). He said ‘Bilal, you have entirely different taste when it comes to filmmaking’, recalls Bilal. It was Manzoor who introduced Bilal to M Maqbool Lone, an entrepreneur and a film enthusiast. “I discussed at least three ideas with Mazoor but he liked The Lost Childhood,” said Bilal.

Manzoor, who has worked as a child labour, immediately offered to fund the project under his banner Arooj Productions. Finally Bilal started working on his first major documentary after coming back from Mumbai. Inspired by Robert J. Flaherty’s famous documentary Nanook of the North, Bilal kept The Lost Childhood a plain narrative documentary with no voice over.

It took Bilal and his team nine months to research the subject alone. “I had to look beyond what was already known,” said Bilal. Made with a modest budget of Rs 2.75 lakh, TLC became first Kashmiri language documentary which got selected for Tehran International Short Film Festival in 2008. In the same year, TLC was selected for Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) under National Special Screening category.

Bilal recalls his maiden meeting with the former Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, SK Sinha, who was a special guest at MIFF. “During our interaction I asked him a few uncomfortable questions regarding Kashmiri film industry,” recalls Bilal. He had asked Sinha why the government has not done anything to help revive the ailing cinema halls in Kashmir which are still under the occupation of forces.

“Kashmir is a troubled state and disturbed area. Hence let us not do anything in haste,” replied Sinha before moving to the next question. On the sidelines of MIFF, the film also won Nina Sughati SR Award for best director for conceptual art of cinema. For Bilal, the success of TLC was because of the efforts his team had put into researching the subject. “Nobody has visited the areas where we shot TLC to highlight the issues of child labour in Kashmir,” said Bilal.

With TLC, Bilal finally realized his dream of making an independent documentary in Kashmir about an issue which concerns his people. But the journey from Mumbai to Kashmir was not an easy one for the idealistic filmmaker. Despite awards and recognitions, Bilal had taken up many odd jobs to sustain his passion for filmmaking. “I worked as a medical representative and a teacher at a private school and was associated with a project called Total Literacy Campaign,” said Bilal.

But survival was not the only thing that kept Bilal on his toes in Kashmir. Having worked with the likes of Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Shyam Benegal in Mumbai, Bilal was forced to manage the shooting in Kashmir with sub-standard equipments. “Filmmakers in Kashmir still use Beta Cam SP while the world has long ago advanced to High Definition,” said Bilal.

Bilal said there are hardly any advanced equipments available in Kashmir. “Filmmakers manage with broken camera mounted on out of balance tripods and sub-standard sound systems. A fresh advanced camera or a boom is a dream in Kashmir. Finding proper sound equipments is the most difficult task in Kashmir.”

In Kashmir, filmmakers have learned to work within the given resources. With no professional sound recorders, no lighting directors available locally, filmmaking in Kashmir becomes a challenging job for people like Bilal. Almost all production houses in Kashmir use second hand equipments bought from Mumbai and Delhi.

Documentary filmmakers like Bilal who usually work on small budgets try to shoot most of the sequences in the day light to save lighting expenses. But if one is making a fiction, then good lighting equipments are required. “We don’t have good technicians in Kashmir. Most people here are in the profession just by chance,” said Bilal.

Working with a limited budget, Bilal completed the actual shoot of TLC in six and half days only. “After the shooting was over, I set out to find a professional editor in Kashmir. And there was not much choice as Jalaal Jeelani is the only person who could compete with the outsiders.” Editing usually cost Rs 1000 per hour (including table charges).

Bilal feels that making a film in Kashmir is altogether a different experience compared to what he has seen in Mumbai or elsewhere. The crew had to carry an electric generator with them as there was no electricity to use lights in the area where Bilal shot TLC. “We had to carry equipments on our shoulders to reach places where we were shooting,” Bilal recalls.

But the young director says the challenges faced during Ocean of Tears were entirely of different nature compared to what he had to face during the making of TLC. In 2010, PSBT called the proposals for documentary filmmaking under various categories. Bilal submitted the idea for Ocean of Tears under the title Broken Silence. “When I developed the proposal, I clearly mentioned Kunan Poshpora and PSBT accepted,” said Bilal. The fellowship was awarded in June 2011.

Bilal and his team immediately started the pre production research work. The research was done under the supervision of Dr A G Madhosh, an educationist, whom the filmmaker appointed as a subject advisor for OOT. It took Bilal and his team two months to research the subject during which they visited victims at Kunan Poshpora and Shopian.

Bilal said the biggest challenge for him as a filmmaker was to convince the victims of Kunan Poshpora to come on camera and narrate their story. Before visiting Kunan Poshpora, Bilal said he was aware of the fact that nobody before him has shot a film there.

“They had lost faith in media. Anybody with a camera was a potential threat for them. They refused to talk saying that the media has used their sufferings for their own interests only and nobody really cares about them,” said Bilal. On his first visit to Kunan Poshpora, the victims and eyewitnesses of the alleged mass rape in 1991 refused to be ‘humiliated’ any further by the outsiders. They told Bilal that we will not talk to anybody. “It was the most challenging phase in my entire film career,” recalls Bilal.

Finally, Bilal managed to convince them to hold a meeting among themselves regarding his request to shot in Kunan Poshpora. “I said all I want is to understand and highlight your pain post 1991,” Bilal said. “They asked what was the guarantee that you too would not use our pain to sell your film in a twisted manner as has happened in the past,” said Bilal.

After the meeting, the village head decided to allow only males to talk on the camera. But, as the subject of Bilal’s film was women in conflict, he was left with no other option but to revisit the village and try to convince them to let women victims come forward and talk about their sufferings. “After four visits, I finally convinced them to let women talk in front of the camera.”

The next stop for Bilal and his team was Shopian. “I wanted to tell the world what really happened to Asiya and Neelofer, the victims of rape and murder case in Shopian,” said Bilal. However, Majlis-e Mushawarat, the local body that spearheads the campaign for justice for Asiya and Neelofer, refused to talk as well.

“I told them I have some questions which need to be answered and cleared,” said Bilal. The Majlis then called a meeting and agreed to let Bilal question them on camera regarding the case. Bilal claims the members of Majlis have not freely talked about the case anywhere and so he wanted their version as well and what they were doing to get justice for Asiya and Neelofer.

Apart from these two already highlighted stories, OOT has some untold stories as well which were not carried by the media. Among that is the story of one Ashma who was allegedly gang-raped by Rashtriya Rifles. But Bilal’s woes were far from over as there was no cameraperson available in Srinagar on these dates and the filmmaker had to arrange one from Jammu. “We managed to get the best sound recorder along with the sound equipments camera and other accessories. I had to hire some of the equipments from Delhi as well,” said Bilal.

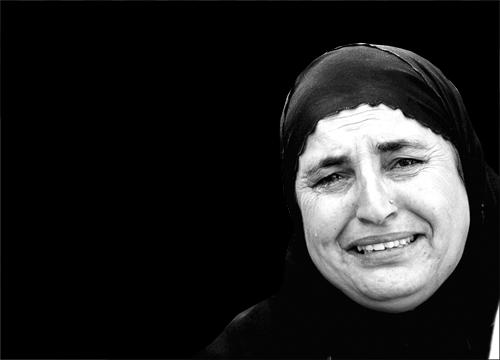

Finally the shooting started and it took Bilal ten days to shoot the entire sequences for OOT. When asked how difficult it was to shoot the victims of Kunan Poshpora, Bilal took a deep breath and said that the entire atmosphere on sets was emotional as the women started to narrate the horrors of rape. The entire team was crying, making it difficult to shoot.

After Bilal was done with the shooting, he submitted a 78 minute edited version of the film to PSBT for their approval. The film was evaluated by Prof. Suresh Chabaria and K Bikaram Singh. Bilal said both the evaluators liked the film in terms of its content research and cinematic mise-en-scene. They also liked the way Bilal had dramatised some of the emblematic montages for the film.

“But PSBT wanted to feature my documentary under 26-minute short film category. So I was told to edit the film accordingly,” said Bilal. One of the evaluators suggested Bilal that he must choose only three or four stories out of the total footage available. He was of the opinion that Bilal should focus on a single subject as the story submitted by him talks of both domestic violence and violence against women in conflict.

The next step was to apply for a censor certificate for OOT. “The reason I applied for a censor certificate was that I wanted to distribute and exhibit my film throughout Indian without any problem.” The censor board passed OOT with a condition that it should carry a disclaimer which would say that the views expressed by different people in this documentary are solely their own views and not against any person, caste, community, religion, institution or organization.

Bilal feels that cinematic mise-en-scene, ambiguity, metaphor and allusions are some of the elements of filmmaking that bind the viewers to a film. “You never know what happens next. You have to catch the viewer’s attention. Cinema is a visual poetry. It’s like literature but a visual literature. A filmmaker should have imagination and observation. Documentary filmmaking has more than five genres but the pure cinematic genre is creative interpretation of actuality, and I follow that,” he says.

Bilal is currently working on another women related issue. The film titled Daughters of Paradise is under production.

Nice article….when can we watch the full documentary

Can you please ask Bilal Ahmad Jan, to youtube or make a DVD of the entire documentary?

I found the inspiring veesrs that may have caused great mayhem in Mumbai and 9/11 and could lead to WWIII.The text below from the Quran seems very clear about the militancy against those who do not share the believers’ faith:(27) O ye who believe! The idolaters only are unclean. So let them not come near the Inviolable Place of Worship after this their year. If ye fear poverty (from the loss of their merchandise) Allah shall preserve you of His bounty if He will. Lo! Allah is Knower, Wise. (28) Fight against such of those who have been given the Scripture as believe not in Allah nor the Last Day, and forbid not that which Allah hath forbidden by His messenger, and follow not the Religion of Truth, until they pay the tribute readily, being brought low. (29) And the Jews say: Ezra is the son of Allah, and the Christians say: The Messiah is the son of Allah. That is their saying with their mouths. They imitate the saying of those who disbelieved of old. Allah (Himself) fighteth against them. How perverse are they! (30) They have taken as lords beside Allah their rabbis and their monks and the Messiah son of Mary, when they were bidden to worship only One God. There is no god save Him. Be He glorified from all that they ascribe as partner (unto Him)! (31) Fain would they put out the light of Allah with their mouths, but Allah disdaineth (aught) save that He shall perfect His light, however much the disbelievers are averse. (32) He it is Who hath sent His messenger with the guidance and the Religion of Truth, that He may cause it to prevail over all religion, however much the idolaters may be averse. (33) O ye who believe! Lo! many of the (Jewish) rabbis and the (Christian) monks devour the wealth of mankind wantonly and debar (men) from the way of Allah. They who hoard up gold and silver and spend it not in the way of Allah, unto them give tidings (O Muhammad) of a painful doom,

It is a grand effort and for this Bilal Jan deserves all the appreciation. One can understand the difficulties Bilal must have faced in his endeavours to tell the world what the hell have human rights’ violation victims in Kashmir gone through. What is important now is how to wipe out some of the tears of victims and help them move ahead in life. What is also important is how best can we help our talented youth like Bilal Jan to continue with the journey they have undertaken. Bilal Jan is a highly talented person , he is young and energetic ; he has the necessary understanding of human sufferings and the courage to stand up and sensitize people about sufferings of innocent men and women. I salute Bilal Jan Sahib for his courage and perseverence and wish him all the success in his endeavours.

Bashir Ahmad Dar