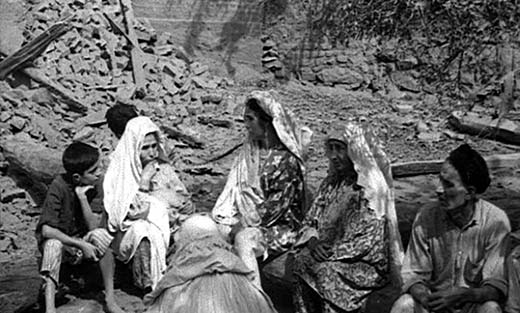

TV suggests that India and Pakistan stand on brink of another war. Even Kashmir is thick with battle talk. War means disaster. Bilal Handoo meets the eye-witnesses of the earlier wars to recount the war horrors that Kashmir witnessed

Out of that militarised village nestled on Line of Control, he walks out every Friday to offer congregational prayers 25km down in Uri town. That day, the gates become slightly more porous in garrisoned Churanda village falling under the LoC fencing.

But these days, Matoo Jinder’s walks remain jittery. Amid peaking Indo-Pak hostilities, he doesn’t want to abandon his crop and cattle — like he did in 1947, ’65, ’71 and ’99.

The hunched octogenarian sporting hennaed beard speaks in a faltering voice. He has seen how wars ravaged those who fell in the line. When the first Indo-Pak war (1947-49) broke out, Jinder was in his late teens. He remembers how armed Pathans from the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan entered the valley ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh, who was yet to decide on accession. When the monarch finally tilted toward Delhi, Indian army flew into valley in Dakotas on October 27, 1947 and war broke out.

“Nobody made sense of that rushed war initially,” Jinder basking under afternoon sun in his courtyard says. “That war went on to alter lives and fortunes.” But before that would happen, the Indian army suffered a setback in December that year because of logistical problems. And then troops from Muzaffarabad forced them to retreat from the margin.

But as war escalated, Delhi under Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru filed a complaint against Pakistan at United Nations on December 31, 1948. In following summer, the UN Commission for India and Pakistan called for an end to hostilities with a truce, to be followed by a referendum for self-determination among Kashmiris. Both the parties agreed to the UN resolution and the war ended.

By then, 1500 soldiers had died on each side, leaving about 30 per cent of Kashmir including Gilgat, Hunza, Nagar, Baltistan under Pakistani control.

Soon, Jinder says, massive migration took place from what had become Kashmir’s frontier areas with people crossing the Ceasefire Line. The movement disintegrated the native population. Those left behind had new neighbours marked with camouflage and jackboots.

“Some big traders and men of fortune lost dear in the war,” Jinder, the eye-witness of first Indo-Pak war, says. “Besides the Jhelum Valley Road connecting Kashmir with Rawalpindi changed the course of valley forever. Kashmiris used to frequent this road to study in Punjab University. But the war blocked it and made Kashmir dependent on Banihal pony road.”

But the biggest tragedy of the war was the forced division of Kashmiris across the Ceasefire Line that later became LoC. Some families got divided by a small stream. “Imagine a scene where a tearful mother longs for her son standing on other side of a stream,” Jinder says. “It was an unfathomable division that drove people crazy for none of their fault.”

Years later, on April 7, 2005, when the cross LoC bus service for members of divided families was started as a CBM between India and Pakistan to bring down the tensions, the reunion apparently evoked more intense emotions than those triggered by the fall of Berlin Wall.

But by the time second Indo-Pak war (August 5 – Sept 23, 1965) broke out, Churanda’s Jinder once again became jittery.

That was one of the most intense wars fought by India and Pakistan—that went on to expose chinks in India’s military armour. And it started after Pakistan attacked India in operation codenamed Gibraltar on August 5, 1965.

Well before Indo-Pak forces would exchange World War-II firearms acquired from Americans, Russians and British — more than 25,000 Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiris had arrived in valley. Indian forces responded violently, launching a bloody summer invasion in Kashmir led by tanks and aerial bombing.

Following initial advances by India in the northern sector, Pakistani forces moved concentrations near Tithwal, Uri, and Poonch. Indian troops went on to capture strategic Haji Pir Pass—8km inside Pakistani territory.

Then in Kashmir’s Batamaloo, Mohammad Shaban—then 25, now 76—had heard arrival of guests from Pakistan through a clandestine radio station Sadai Kashmir. Popular among Kashmiris, the radio was launched to rouse passions and pass on information. On August 1965, it announced that armed rebellion broke out in Batamaloo. Shaban heard it announcing that Pakistani soldiers in civvies have taken over Srinagar. Pakistanis, according to the radio broadcast, were just 2km away from Civil Secretariat.

Those were the Gibraltar forces armed with rifles. But the panic had already turned the lively Batamaloo into a ghost town. What hastened the migration were the nocturnal fireworks by forces.

Meanwhile to take Akhnoor bridge and cut off the lifeline of supplies to southwest Kashmir, Pakistan launched Operation Grandslam. The subsequent Pakistani attack in the southern sector in Punjab inflicted heavy losses on Indian side on September 1. A day after, Delhi called in air support, which was retaliated by Pakistani air strikes in Kashmir and Punjab.

“Then in Srinagar and other parts of valley,” says Shaban, recalling the war in the times of civil uprising inside his windowpane smashed residence in an apparent war-torn Batamaloo, “people would throng to rooftops to wave at Pakistani Cyber Jet airplanes doing rounds in Kashmir skies. Everybody was batting for Pakistan’s victory. Some people even spread a grapevine that a lady Pakistani pilot—Jameela—flew her aircraft over Dal Lake and plucked Lotus from it. It was one hell of an adventurous time.” But shortly, the flames engulfed Batamaloo and forced armed guests to retreat.

The entire Batamaloo inhabited by Muslims was razed to the ground. Fire consumed around 440 houses, The Washington Star reported on September 1, 1965. “Many Muslims were burnt alive in this suburb by the Indian Army. Indian officials claim Pakistani infiltrators started the fires. But both extremist and moderate Kashmiris and the victims themselves, interviewed while digging in the smouldering wreckage, claim the Indian army was responsible.”

By September 20, UN Security Council unanimously passed a resolution, forcing Delhi and Islamabad to end war. The war ended on September 23, 1965—not before it officially devoured 3,000 Indian and 3,800 Pakistani troops.

General Musa Khan, then commander-in-chief of Pakistan army wrote in his book My Version that the Kashmiris weren’t taken into confidence about the operation aimed to “liberate” them. But it was “the best opportunity lost for Kashmir’s freedom”, Sheikh Abdullah’s confidante Munshi Mohammed Ishaq said.

After the blaze, Batamaloo changed forever. People were barred from reconstructing their gutted houses, paving way to bazaars and bus stand. Rebuilding that followed reduced a ‘self-sustaining’ community to mere consumer marketplace.

To resolve the war, India and Pakistan entered into Tashkent Declaration. But Kashmir passed through a camouflaged change. Highland pastures, plateaus and hills became highly militarised. People lost major landholdings to garrisons that alarmingly mushroomed across the valley. Even protracted courtroom battles couldn’t relieve people’s land from the throes of “national security”.

By the time third Indo-Pak war (1971) broke out, Srinagar Airport became an apparent war-turf. Despite two neighbours fighting it outside the territorial limits of Kashmir, heightened military footfalls deserted an airport village, Gogo.

A village elder Abdul Rehman still remembers tensions triggered by the war that Delhi fought to liberate East Pakistan. Before the battle, a revolt following detention of Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rehman had started in 1970. Pakistani army cracked down in East Pakistan, triggering mass migration to India. A Pakistan airstrike on Mukti Bahini camps located inside Indian territory in West Bengal displeased Delhi under Indira Gandhi. On December 3, 1971, Pakistan Air Force struck Indian airfields in northern India. By midnight, India was officially at war with Pakistan. Delhi had quietly sought and got arms from Tel Aviv, writes a scholar Srinath Raghavan in his book, 1971. At the end of that 14-day war, East Pakistan became Bangladesh on Dec 16, 1971.

“Throughout the war period,” says Rehman, “we were inside trenches dug on our farmlands.” The moment they came out, their life had changed. Most of their farms were occupied by army. “And when we went to our farms, army forced us out,” the village elder says.

The villagers took the matter to court where the final settlement fetched them a paltry Rs 2600 per kanal. The war went on to consume hundreds of kanals of land in Gogo. Later on the same land, a dreaded torture centre Gogoland came up during early nineties. Today, this tarmac village looks more of a garrison.

But with the fall of Dhaka, the mood had badly soured in valley. Kashmir went into instant mourning. “But the biggest war destruction was the change in Sheikh Abdullah’s heart,” says Zareef A Zareef, a noted poet-historian. “After the creation of Bangladesh and subsequent signing of Simla Pact on July 2, 1972—wherein both countries agreed to respect the LoC until the issue is finally resolved—Sheikh thought running Plebiscite movement at behest of fragmented Pakistan is hopeless. And then, he shortly signed that Accord.”

Years later when the top rebels of nineties were asked what prompted them to settle the matters with guns, some of them cited 1975 accord that saw Kashmir’s “towering leader” junking the plebiscite movement. This made many believe that 1971 war was indeed a “bad bargain” for Kashmiris.

By the time India and Pakistan locked horns fourth time on uneven ridges of Kargil in 1999, the entire Kashmir anticipated brutish battle consequences. By fighting the war at the frozen heights of Himalayas, many Kashmiris thought Pakistan’s invasion was aiming at slicing off the Ladakh in an apparent pay back of 1971.

That televised war had begun after army patrol had seen gunmen prowling in the Batalik sector on May 8, 1999. They were equipped with medium machine guns, heavy mortars and sophisticated small arms. By May ending, Premier Atal Behari Vajpayee announced a “war-like situation” in Kargil. On June 6, the army launched Operation Vijay, accompanied by air strikes. For Delhi, the objective was to keep the crucial Srinagar-Leh highway free from any Pakistani threat.

Finally when US President Bill Clinton urged Pakistan to pull out off Kargil, Premier Nawaz Sharif announced the end of the war on television on July 12 and proposed talks with Vajpayee.

That war wound off many businesses in Kargil, forcing many Kashmiri traders to return home. But the war apparently clicked for Kargil. It triggered a new tourism boom in the cold desert: patriotic tourism. People from different parts of India started visiting the place of war and war memorial. Many hotels and restaurants came up in Kargil to accommodate the visitors.

17 years after the Kargil war, Churanda’s Matoo Jinder is badly perturbed over the possibility of another war. Life in his fringe village has been thrown out of gear after “surgical strikes” and subsequent full-blown war theories started doings rounds.

Last time, when the war broke out, the villagers had taken shelter inside bunkers dug on farmlands. But Oct 2005 earthquake decimated everything including traditional kothas and underground bunkers.

“Now, the kind of houses we dwell will be blown to pieces by a small shell,” Jinder says. “In case, there is war now, I don’t think, anybody will survive to recount the war stories anymore.”

Amid tensions, the question remains — is the fifth war between two nuke-armoured neighbours on? Jinder says he lately saw troopers doting LoC with white flags—an Olive Branch, perhaps. But then, were those anti-aircraft guns and a tank seen recently inside Baramulla district hospital premises just for public posturing?

Well, down in Srinagar, they have already started talking: So much for Alpha Charlie!