The dispute over use of Kashmir waters is heating up Indo-Pak relations raking up threats of war and a lot of propaganda. Iftikhar Gilani reports on the vitality of the issue and the state of Kashmir glaciers.

Climate change and water is fast emerging a new irritant in the already plummeting India and Pakistan relations. At a recent meeting to formulate agenda for the forthcoming SAARC summit, India had to withdraw its representative Yogeshwar Verma, joint secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs, after he almost came near to blows with his Pakistani counterpart, who was pressing to include issue of water in the agenda.

Climate change and water is fast emerging a new irritant in the already plummeting India and Pakistan relations. At a recent meeting to formulate agenda for the forthcoming SAARC summit, India had to withdraw its representative Yogeshwar Verma, joint secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs, after he almost came near to blows with his Pakistani counterpart, who was pressing to include issue of water in the agenda.

The summit scheduled in Bhutan on April 28-29 is focusing on climate change issues. India has since sent new representative Harshvardhan Shingla. But as last reports suggest officials have expressed inability to sort out the differences and, all matters have now been referred to SAARC standing committee of foreign secretaries that is scheduled to meet in Bhutan ahead of the summit.

During last foreign secretary-level talks in New Delhi Pakistan Foreign Secretary Salman Basheer presented a paper on climate change issues to India, prepared by Pakistan’s Indus Water Commission.

Although water is not a core issue for the resumption of talks between the two nuclear neighbours, differences over the use of rivers assigned according to the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty have undercut peace-making efforts.

When Pakistan’s chief negotiator on climate change, Farukh Iqbal Khan had called on minister of state for environment, Jairam Ramesh, ahead of December Copenhagen summit , they expressed the need to coordinate and evolve a common stand lest the developed nations thrust their emission standards and other positions on developing countries like India and Pakistan. “We had a useful discussion. We decided to coordinate our positions. The issue of climate change may help us to break diplomatic logjam,” said Ramesh, referring to his meeting with the Pakistani official.

However, there is burning need for both countries to sort out some pressing environmental issues bilaterally. Since the issues are linked to farmers in the Pakistani heartland and touch the lives of ordinary citizens, they need to evolve a mechanism beyond political rhetoric.

However, there is burning need for both countries to sort out some pressing environmental issues bilaterally. Since the issues are linked to farmers in the Pakistani heartland and touch the lives of ordinary citizens, they need to evolve a mechanism beyond political rhetoric.

There may not be the scientific evidence on the melting of glaciers. But there is fairly a large “anecdotal evidence” to suggest that major Himalayan glaciers, sources of major rivers in India and Pakistan were receding. Almost all the Indus line glaciers, Pakistan’s water houses, are melting and receding at an alarming rate, more rapidly than other Himalayan glaciers. The nose of the Kolhai glacier in Kashmir, one of the largest glaciers in the Himalayas, was recorded to have receded by almost 22 metres in 2007, while several smaller adjacent glaciers have disappeared completely. Almost 15,000 Himalayan glaciers form a unique reservoir which supports perennial rivers such as Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra, which are the main source of fresh water for billions of people in the region.

Ironically, while India has taken tough measures restricting tourist and pilgrim traffic to save the Gangetic glaciers, it tends to sidestep the Kashmir glaciers, which are source of water for the Indus and the Jhelum. Blinded by politics to whip up communal passions on land allotment to the Amarnath Yatra board in Kashmir Valley last year, Bhartiya Janata Party(BJP) overlooked a report prepared by its own NDA member Dr Nitish Sengupta in 1996 asking for regulating number of Amarnath pilgrims to preserve the fragile ecology and environment of the region. The forestland handed over to the Shri Amarnath Shrine Board (SASB) at Baltal near Sonamarg houses the Nehnar and Thajwas glaciers.

It is interesting to note that the BJP government in the north Indian state of Uttrakhand applied Dr Sengupta’s report in Gangotri, where in May 2008 they issued a notification restricting the number of pilgrims and tourists to 150 a day to visit Gomukh, the origin of the holy river Ganges. Gomukh is as holy a shrine for Hindus as Amarnath in the southern mountains of Kashmir. Last year, despite disturbances, half a million pilgrims visited the Kashmir shrine over a period of two months.

Over 20,000 pilgrims are at the cave shrine against the recommended 3,000 per day, plundering the glaciers. Glaciologists have also raised fears of environmental degradation, ecological imbalance and adverse impact on the Nehnar glacier, situated at a height of 4,200 meters around Baltal near Sonamarg, from the heavy rush of pilgrims.

In a decision that shows heightened sensitivity towards the environment in Uttrakhand, the government recently shelved two projects, the 381MW Bhaironghati and 480MW Pala-Maneri hydroelectric plants — planned on the Bhagirathi, one of the key tributaries of the Ganges to allow its flow untamed and unchecked through the year.

In a decision that shows heightened sensitivity towards the environment in Uttrakhand, the government recently shelved two projects, the 381MW Bhaironghati and 480MW Pala-Maneri hydroelectric plants — planned on the Bhagirathi, one of the key tributaries of the Ganges to allow its flow untamed and unchecked through the year.

The decision, taken last week by a three-member group set up by the prime minister was prompted by religio-political and environmental considerations, and marks a big shift from the days when the government would disregard dissent on dams.

Referring to the Amarnath pilgrimage, Prof MN Kaul, former principal investigator on glaciology at the Department of Science and Technology said in a paper he presented in 2005; “it is for the first time that the Baltal route has been exposed to heavy pilgrim traffic, which is likely to affect the ecological balance and the health of the Nehnar glacier.”

Environmentalists have often raised concern that apart from the sewage generated by pilgrims, they also throw tons of non-biodegradable items made from polythene and other plastics directly into the river. This has resulted in the deterioration of water quality.

Environmentalists have often raised concern that apart from the sewage generated by pilgrims, they also throw tons of non-biodegradable items made from polythene and other plastics directly into the river. This has resulted in the deterioration of water quality.

One expert, MRD Kudangar, has recorded that chemical oxygen demand of the river has gone up to 17 and 92 mg per litre, which is beyond permissible levels. Water with such levels of chemical pollution cannot be recommended for consumption.

It has been estimated that every day during the pilgrimage, 55,000 kg of waste is generated. Apart from this waste, the degradation caused by buses and vehicles carrying pilgrims, trucks carrying provisions and the massive deployment of security forces further contribute to air pollution.

Another factor is the threat posed to local inhabitants from the crowding of an ecologically fragile area where they have to compete to retain their access and rights to resources – both water and land.

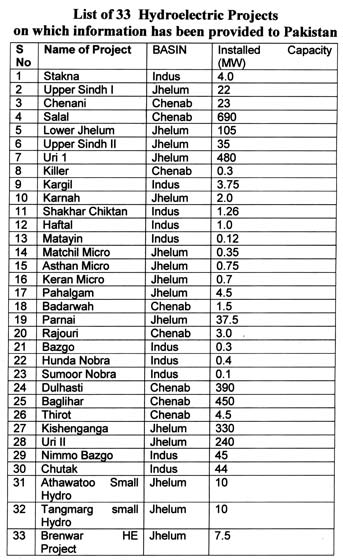

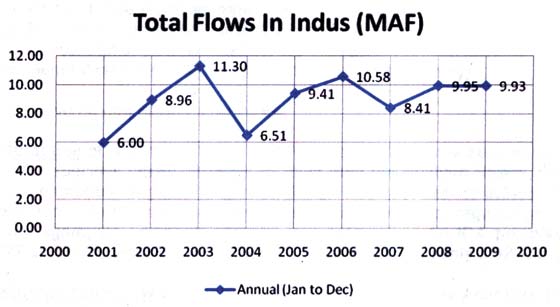

Recently Jairam Ramesh also agreed that most countries have regulated tourist inflows into their mountainous regions. India’s national environment policy also calls for measures “to regulate tourist inflows into mountain regions to ensure that these remain within the carrying capacity of the mountain ecology.” A UN-sponsored study, “Mountains of Concrete: Dam Building in the Himalayas” predicted dramatic decreases in flows in the Indus basin in 100 years.

Recently Jairam Ramesh also agreed that most countries have regulated tourist inflows into their mountainous regions. India’s national environment policy also calls for measures “to regulate tourist inflows into mountain regions to ensure that these remain within the carrying capacity of the mountain ecology.” A UN-sponsored study, “Mountains of Concrete: Dam Building in the Himalayas” predicted dramatic decreases in flows in the Indus basin in 100 years.

The study, undertaken by Sripad Dharmadhikari of the Manthan Adhyayan Kendra for International Rivers, predicts extreme changes in river flows due to global warming and climate change. As glaciers melt, water in the rivers will rise and dams would be subjected to much higher flows, raising concerns about dam safety, increased flooding and submergence. And with the subsequent depletion of glaciers, there would be much lower annual flows, affecting the performance of dams, built with huge investments. Unfortunately, even dam construction was being planned without any assessment of these impacts.

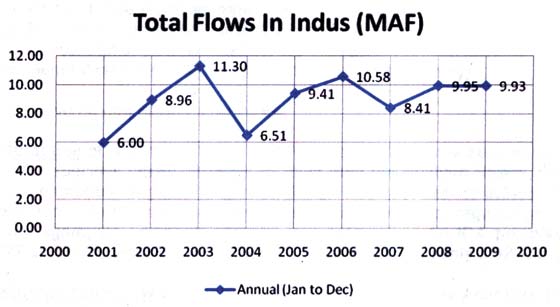

Half a billion people in the Himalaya-Hindukush region and a quarter billion downstream who rely on glacial melt waters could be seriously affected by what is happening to the glaciers. The current trends in glacial melt suggest that the Indus and other rivers may become seasonal rivers in the near future as a consequence of climate change with important ramifications for the economies in the region.

An Action Aid report has also warned that melting of Kashmiri glaciers could trigger massive food security problems in the near future. It said some glaciers have already disappeared as a result of which discharge in streams has significantly gone down.

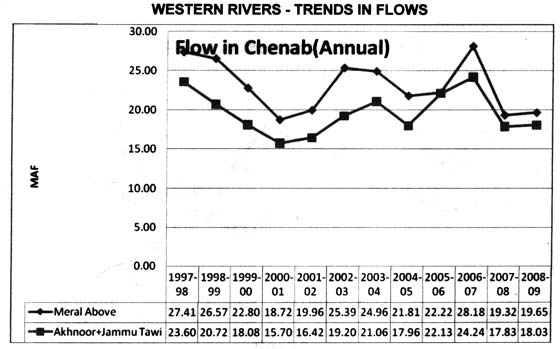

The report, a study identifying the impact of climatic change at the micro-level, said a 21 percent overall reduction has been found in the glacier surface area of the Chenab, a sub-basin of the Indus. Of the 327 major glaciers in the Himalayas, 60 are in Kashmir and Ladakh.

According to the report, while some glaciers have vanished, the surviving ones are fast shrinking. In the Sindh valley, for instance, the Najwan Akal glacier has disappeared, and the surviving trio – Thajwas, Zojila and Naranag – have shrunk considerably. The one feeding the Amarnath cave has reduced by over 100 meters in one year.

Similarly, the Afarwat glacier near Gulmarg has ceased to exist, though once it happened to be 400 meters long.

The report says this is happening everywhere, from north to south. Almost all the major glaciers in south Kashmir – Hangipora, Naaginad, Galgudi and Wandernad – are shrinking. It carries no supporting data, which in certain cases was available with certain official agencies.

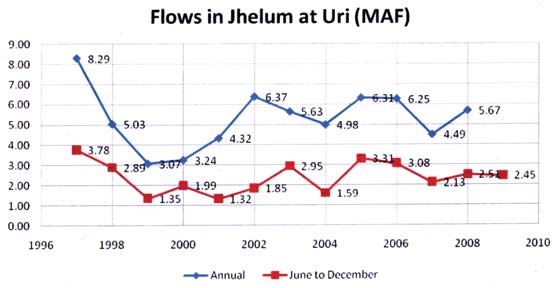

Barring certain water bodies that are spring-fed, most of the streams of Indus water system are glacier-fed. Since early melting triggers massive discharge in rivers, the water bodies lack the adequate quantity once agricultural activity begins. The report says that while snow and rainfall have reduced, temperatures have risen a bit. Early melting triggers flash floods, and fall in water discharge impacts agricultural production, which according to the report is otherwise affected by arbitrary land use.

The report has tried to link the possibility of heat-trapping gases in Kashmir’s “almost closed environment” with the melting of glaciers and other indications of climatic change. Kashmir’s forest area has shrunk considerably, from 37 percent of its total area to merely 11 percent now. Barely 20 years ago, the snow line to the Kashmir valley’s east was just above areas like Pahalgam and Sonmarg (3,200 meters).

“Currently the line has receded to Shishnag area which is at an altitude of 5,000 meters only. Same is true of the Pirpanjal mountain range in the west where the snow line was above Kongwatan and Zaznar (3,000-3,500 meters)”.

Most of the glaciers of the Great Himalayan range, from Harmuk to Drungdrung, including Thajiwas, Kolahoi, Machoie, Kangrez and Shafat, have significantly receded (4,000-5,000 meters) over the last 50 years. According to testimonies of villagers in the Choolan area, located in the Shamasbari mountain range in north Kashmir, the nearby glacier, Katha, has reduced from 200 feet to 80 feet over the last 40 years. Similarly, people living around Tangmarg and Gulmarg in North Kashmir say the Budrukot glacier in the area has reduced from 16 feet to only 5 feet in height over the years.

The Khujwan glacier in the mountains of the Kichama area has reduced from 40 feet to only 20 feet over the years. The Afarwat glacier around the Nambalnar Hajibal area, which used to be 300 feet long 40 years ago, has completely disappeared.

Fifty years ago, the Chenab basin used to have about 8,000 sq km under glaciers, permanent and ephemeral snow cover which would contribute huge quantities of water during summer to this river through numerous perennial tributaries as compared to the present 4,100 sq km under snow cover. In the Pirpanjal range, there is hardly any glacier remaining at the top of this mountain range; the terminal morains at Akhal (Rajpora) on the Romshi river, Dubjan on the Rambiyara river and Gurwatan on the Veshuv river bear testimony to the fact that glaciers once extended up to these places in the recent past. If the situation continues like this, all rivers flowing from the Pirpanjal range will lose their perennial status and will become ephemeral.

On the ground, the picture may be even more horrific than portrayed here. Terrorism may be the biggest threat to innocent lives in the region, but the environmental catastrophe will affect generations and cost more lives than any other threat.

Therefore, it is surprising that these issues have not received much attention in the diplomatic circles of India and Pakistan.

It is imperative for both neighbours to evolve a mechanism beyond the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) and hold water-sharing talks to save the sources of water. There is greater need to set up a cooperative mechanism to govern and protect resources across the Line of Control.

One cannot expect the Indian exchequer to spend on the protection of resources where India is not directly benefiting. It is Pakistan and its farmers who have a vested interest in the protection of such resources in Kashmir.

Another way out could be to expand the mandate of SAARC to prioritise greater cooperation on environmental issues. There is also need to set up monitoring committees for resource management. Still another way to foster environmental cooperation could be to expand knowledge and data sharing mechanisms.

Security is no more confined to national security threats or international relations. Environmental changes are now being listed as security threats. Richard Ullman defined threat as “…anything which can degrade the quality of life of the inhabitants of a state, or which narrows the choices available to people and organisations within the state.” It is time for both India and Pakistan to redefine their strategies and attend to this issue, which has far reaching consequences for their people.