Governance failure apart, societal corruption, greed and biotic interventions in fragile ecology invited Rs 100,000 crore catastrophe to the City of Kashmir. R S Gull identifies factors that policy makers must consider while drafting a futuristic blueprint for Kashmir’s modern capital

(A view of Jhelum flowing over Bund. KL Image Bilal Bahadur)

Historically, Kashmir’s calamities have revolved round three Fs: famines, fires and floods. Key to mass murders in a society that remained entangled in induced strife, it had many eras when all the 3Fs existed at the same time.

While slightly responsive governance and improved seed management reduced famines (the last one was in 1957) and better building sense managed conflagrations, managing floods have remained a pure science in Kashmir for most of its recent history. While one autocrat started large-scale dredging, another invested massively for alternative channels. Even before Dogras’, historic evidence suggests rulers added to the crisscross of city’s canal-structure to improve its drainage capacity.

Totalitarian Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad was the last ruler who invested massively on Jhelum catchment downstream Srinagar for improved embankments. He is credited for converting Sienwari (low lying garden) into Sonawari (golden garden). Barely a decade later or so, the systemic intervention dictated by the political executive started undoing the improvements. The gradual deterioration led to the collapse of the overall systems. Amid loud-thinking on the wrongs which led to catastrophe, experts from various streams have identified a set of reasons that failed Kashmir to save Srinagar. Not many lives lost but the costs of the historic inundation are immense.

CHANNEL CHOKING

(The erstwhile Nalla Mar, a canal that crisscrossed the old Srinagar, it was filled up recently to pave way for a road.)

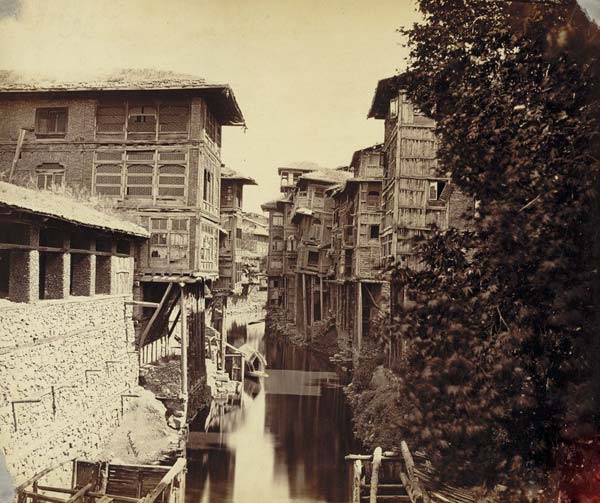

Between Budshah and Dogra’s, quite a few rulers skipped adding more space to waterways. Even ruthless Afghan era Amir Khan created a nulla to add to city’s canal network. These channels led some people terming Srinagar as the Venice of East, a comparison that raises eyebrows in Europe. Flood spill channel (FSC) was the last of these man-made creations that helped Srinagar breathe easy during floods as they would accommodate Jhelum’s most of the discharge.

These channels were literal roads required for transporting grains, merchandise and fuel-wood to the people living on their banks. They would take off from the river and after traversing some distance in the city would rejoin it.

Tchunt Koul takes off from Ram Munishibagh, touch the mouth of Dalgate, reach Barbarshah, and rejoins Jhelum in Gaw Kadal.

Originating near Zaina Kadal, the Kaet Koul rejoins the river at Nawa Kadal after passing through Nawab Bazar, Thugbab Saeb and Watal Kadal.

From Kani Kadal takes off the Sounar Koul and re-embraces Jhelum near Chattabal Weier after travelling a longer distance between Fateh Kadal, Medical College, and Daresh Kadal.

Nalla Maar was perhaps the longest of them all. Taking off from Nawpora, it would cross Babademb, touch Khanyar and go to Rajouri Kadal and Safakadal and then bifurcate to rejoin the water bodies in two different directions.

The Nulla Amir Khan would take off near Pukhri Bal from Nigheen then cross the bridge, and connect Gilsar with Khushalsar. The only modern day intervention was using this stream to connect Nigheen with Anchar lakes.

The status of these channels is that Nulla Maar is a road with unending line of shops on both sides. It was filled post-1975 for security reasons. Engineers say filling this channel was the worst policy failure in city’s water management that paved way for bigger blunders in the subsequent years. At least half a dozen water bodies linked by this channel, a major tourist attraction for centuries, were blocked and gradually converted into cesspools.

An extension of Doudh Ganga is completely lost between Alochi Bagh and Chattabal with its remnants still visible. All other channels are chocked festering drains that exist only during floods.

SOWING SOIL

Deforestation is an uninterrupted exercise across J&K and it is key factor for soil erosion. A not so recent study by the Central Soil and Water Research and Training Institute suggests that J&K losses over 5,334 million tones of soil, annually. Where does it go? – 29% lands in sea, 10% is deposited as silt in water bodies and 61% is displaced.

Massive soil erosion makes Jhelum shallow and shrinks its retaining capacity. Huge shoals of silt and gravel even deviate its course gradually. Wullar Lake becomes shallower by six inches every year.

Silt has already destroyed most of the lakes, wetlands and marshes which act like sponges during floods. Dal has shrunken a lot. Anchar has ceased to exist as a lake. Gilsar and Khushalsar were silted up by the Sindh. Narkara-Nadru-Bemina belt that would shroud the Hokersar are done away with as they lack any capacity to retain any water. Some of these spots might still be attracting migratory birds but their active existence as part of the extended basin is over. Now these belts trigger backflows which add to the crisis.

Even Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) has a point. Its report says the catchment area of the Dal Lake is 314 sq km, of which 148 sq km is prone to soil erosion. The open area of the lake stands reduced to 12 sq km from 24 sq km and its average depth also reduced to three meter because of siltation. For this reason the lake’s ability to naturally drain out flood waters has greatly suffered, it says.

The consequences are disastrous. Writing for the 12th World lake Conference in 2008, Humayun Rashid and Gowhar Naseem – two researchers at the State Remote Sensing Centre’s GIS laboratory, made a startling revelation after comparing the area under water in 1911 and 2004 – two years separated by a span of 93 years.

The open water surface was 4000.50 hectors in 1911. It was reduced to 3065.88 hectors by 2004, a net loss of 934.62 hectors. Wetlands and marshy areas exhibited a much serious crisis. They measured 13425.86 hectors in 1911 and were reduced to 6407.14 hectors in 2004 – a net decrease of 7018.72 hectors. It means we destroyed more than 52% of the wetlands and the marshes in last 93 years!

The lost wetlands include Galender, Busar, Chandmari, Baghi Nand Singh (Batamaloo) and a major portion of Sonawar and Indra Nagar.

DREDGING DILEMMA

Helping Jhelum improve space for more discharge, rulers had made dredging a routine process. During Suya’s time, legends suggest rulers would throw golden coins into the river so that people dredge out the silt in the greed of money!

After the ‘great’ flood with nearly 100000 cusecs of discharge devastated Srinagar in 1903, Britons forced Kashmir autocrat to have a substantial flood management plan. Two options were approved.

Firstly, creating a 41.70 kms long flood spill channel (FSC) for 17500 cusecs of discharge from river upstream bypassing Srinagar.

Secondly, dredging the river bed between Sopore and Baramulla to increase water velocity. Jhelum bypasses Dal Lake but lands in Wullar. Removing silt at the Wullar’s mouth between Sopore and Baramulla was considered the key intervention that will drain out floods faster. After the American machines were imported, the requirement of energy led to the setting up of Mohra power station – that gave Kashmir the distinction of being the second place in subcontinent after Mysore to have hydropower. That energy was primarily for the dredgers and the surplus would enlighten the palaces in Srinagar. After 6100 acres of silt was dredged out and river velocity improved, all the equipment was sold as junk in 1917.

The only post-partition intervention was in 1959 when dredging was resumed with the creation of Flood Mechanical Division (FMD) that acquired lot of modern gadgetry. Dredging stopped in 1984 when it had removed only 1255 lakh cfts against the total deposits of 1438 lakh cfts in the crucial 8 kms stretch affecting its velocity. By the time, FMD wanted to get revived, most of its hardware had drowned.

Understanding the inevitability of the old practice, Congress minister Taj Mohiuddin resumed dredging downstream and started improving the capacity of FSL, reduced to 2800 cusecs. While he was in the middle of it, he was shunted out to another ministry. His successor stopped both the operations in 2013 summer!

Interestingly while all the canals are being repaired and dredged every year in Jammu, the process is halted totally in Kashmir. Owing to this crisis, a number of tributaries of Jhelum have changed course at many places because of the shoals. Right now every major rivulet needs massive bulldozing of the accumulated silt that many people are using to reclaim land for orchards and paddy fields.

BASIN BUNGALOWS

(An Aerial view of inundated Jawahar Nagar Srinagar.)

Humayun – Gowhar research has another shocker. In last 93 years, the built up area in Srinagar has jumped to 10791.59 hectors in 2004 from 1745.73 hectors in 1911 – a phenomenal increase of more than 500%.

As soil erosion helped eutrophication of water bodies, the landmass was claimed quickly by the state and the people.

Srinagar has swelled a lot. Zadibal and Buchwara were added to the municipality in 1915, Batamaloo and Sonawar-Shivpora followed in 1923. From 28 sq kms in 1960 to 177 sq kms in 2000, Srinagar consumed every single inch before starting encroaching upon the peripheries of Ganderbal, Baramulla, Bandipore, Budgam and Pulwama districts. Omar’s cabinet on Friday approved extension of Srinagar’s municipal limits from existing 416.25 sq kms to 757 sq kms by including 163 more settlements. But the leap-frog development is haphazard and harmful.

Old Srinagar was all right but the modern Srinagar is a flop. All the flood basins were made habitable and sexed up as posh addresses: Rajbagh, Kursoo, Jawahar Nagar, Gulbarag Colony, Nowgam, Tengpora, Pir Bagh, Shivpora, Indra Nagar, Bemina.

Government took the lead in encouraging the people to live dangerously. Bakhshi wanted to keep Nehru in good humour so he converted a vast vegetable garden into Jawahar Nagar, the worst sufferer of 2014 flood. Indira Nagar was to please Mrs Indira Gandhi. Sadiq has no option but to build a “modern” Batamaloo on the ruins of the devastated habitation during 1965 war. Bemina was the first state promoted locality after 1975 when the erstwhile Plebiscite Front followers wanted their share of fortune. Now best of state assets are located there.

“My locality (Parraypora – Baghat) was green belt in 1977 plan,” says lawmaker Naeem Akhter. “Later, Sheikh Sahib permitted Mohan Kishan Tickoo, the judge in Kashmir Conspiracy case whom he had made his minister and then all others followed.”

Politics was at the core of undoing of Srinagar. When Dr Naseer A Shah wanted to build home, Sadiq refused permission despite the proximity the families had. Later, he got the permission. But that started an unending process of commercialization between Dalgate to Nishat. A general belief is that autocrats oversaw the evolution of Srinagar on scientific lines. When democrats replaced them, they handed it over to land-grabbers and Drauls! The government is fast filling up Rakh-i-Arth to rehabilitate Dal dwellers and it is also part of the extended flood basin.

POLICY PRALYSIS

With normal discharge, if Wullar outlet is blocked, Kashmir will survive for three days. But the lake lacks space to manage such a massive discharge as Jhelum drained from south in 2014.

But that does not impact the policy makers who conveniently agreed to the diversion of major discharge from Neelum (Kishangaga) river from Gurez to Bandipore. This water being transferred through a 22-kms tunnel would produce energy at Bandipore for NHPC’s 330-MW Kishangaga project and then get into Bunar Madumati Nullah and eventually into Wullar Lake. If Kashmir lacks space for the water it already has, why add to the crisis?

This is one of the classic instances of crisis-creation at the policy making level. Recent flood witnessed the costs going up primarily because of two pieces of communication infrastructure built quite recently: the railway track and the upcoming alternative highway passing through the middle of apple orchards and the saffron fields.

The railway track that connects Qazigund and Baramulla through Islamabad, Pulwama, Srinagar and Budgam actually slices the valley into two parts – the upper Valley and the lower Valley. Though railway engineers have kept small ducts for petty streams to stay connected under the track, there is no adequate connectivity for water if these streams fill up. This has resulted in water logging of the areas hitherto untouched by floods.

When the central government started executing the gold quad, some senior officials in J&K had suggested the new road between Srinagar and Qazigund should follow the foothills. They pleaded that taking road through the middle of the leftover plains would create another hazardous divide and devour swathes of fertile land thus adding to landlessness and unemployment. As always, they were overruled. While the road is yet to come up, the impact of massive embankments on the people living on its two sides offers just a glimpse of how investments can go bad.

ENIGMATIC ENGINEERING

(Aerial shot of devastated Bund.)

Given the limitations of the space, massive discharge of Jhelum was supposed to overflow. But it might not have been so ferocious had there been enough of room for its fast passage. Engineers had created two bottlenecks in the main river as well as in the FSL.

For the last three years the JKPCC is building a bridge between General Post Office (GPO) and the Presentation Convent. Apparently a political project, the government suppressed opposition to it. But it could not complete it. The massive obstructions triggered backflow in the main river and forced excess water to the banks on both sides.

Same is true with the causeway that connects the Jawahar Nagar side of the FSL dyke with Mehjoor Nagar. It was laid to ease the pressure on traffic created by the upcoming fly-over. It also acted like a block and triggered backflows.

The supervision part of the embankments had apparently being done away with. The river chose the weakest spots and most of them had skipped the eye of the Irrigation and Flood Control department. A major breach near Shivpora took place near a protected embankment stretch that had least movement of people because of concertina barriers raised by the security men. Same was the case near the erstwhile Srinagar Club. Even at a few places the breaches followed the encroached spots where there was enough room. A water lifting point near Sempora was an ideal entry passage for the flood because there was enough of room.

Though top engineers asserted the use of bund for passage of a massive pipeline, simply buried without concreting, was all right, there is an alternative contrarian theory to it. At many places the floods started getting in through dewatering outlets, located dangerously.

GOVERNANCE GLITCH

(Army during rescue.)

Second identity of Kashmiris is being boatmen, courtesy tourism. But where are the boats? Had not people innovated and availed the jugaad option, death toll in Kashmir might have been in thousands. Authorities have stopped offering timber to houseboats and Shikaras owners. Now quite a few carpenters survive who know the art of making these water wonders. Though not many shikaras are there, most of them could not be mobilized in time.

Nobody ever raised the question about the number of rubber or motorized boats that Kashmir owns.

Despite being flood prone, J&K is a rare state that lacks a flood warning system. Srinagar must be outnumbering all other states in bullet proof vests, but it may not have even 100 life saving jackets that rescuers could use during floods.

J&K’s inability to raise State Disaster Response Force (SDRF) despite availability of resources is a key question mark. After the floods, they are now getting attention to acquire whatever they require. It was almost in the line of I&FC department toying with the idea of purchasing 10 crore bags for dyke-protection, three days after the flood water was in Rajbagh!

While there were a number of exercises to identify the encroachments on Jhelum, a serious effort to clear it has not started yet.