A series of civilian killings including five non-native workers have pushed Kashmir into a credibility crisis and an economic mess at the same time reports Minhaj Masoodi

In Srinagar outskirts, a lane branching off from the Baramulla highway near Shalteng was the main address for the non-local workforce. Living on rent, they mainly came from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Every morning, they used to gather at Shalteng Chowk and wait for the clients, mostly those constructing their homes. For almost a week, the bustling square presents a deserted look. Many of these non-locals have already left after some of their colleagues were attacked and killed by unknown gunmen, suspected to be militants by the police.

Many of them have already left and those staying put are packing their belongings. One among them is Mubarak Alam, a painter, who has been earning his livelihood in Kashmir since 2005 summer. This time, Alam is terrified because of the recent killings. Accompanied by his family, he has ceased working and wishes to move out prematurely.

“I have never felt this unsafe in the twenty years that I have worked here,” said Alam. “We don’t know who will be targeted next. It is better to leave till things calm down and see what happens next year.”

Rajesh is hailing from Bijnor in Uttar Pradesh. Though most of the residents from Bijnor and its immediate surroundings control Kashmir’s hairstyling sub-sector (more than 2000 families dislocate to Kashmir for most of the year), Rajesh is a mason. These days, he also shares a similar concern. This is the first time, he said, he felt “this level of threat” in his life while working in Kashmir.

A Spate of Killings

Kashmir witnessed a surge in civilian killings this year, around 30 this year, so far. In the last fortnight, at least 11 civilians lost their lives. These included members of Kashmir’s minority communities, and non-natives earning their livelihoods.

On October 5, when pharmacist Makhan Lal Bindroo was shot dead at his shop, it coincided with the killing of Virender Paswan, a street food vendor at Lal Bazar.

On October 16, two more non-locals were killed in separate attacks- Arvind, a street food hawker from Bihar was shot dead at Eidgah, while a carpenter, Saghir Ahmad from Bihar was killed in Pulwama’s Litter area.

A day later, on October 17, unknown gunmen fired at three more non-locals by barging into their accommodation. Two of them succumbed to their injuries while the third was shifted to the hospital in critical condition.

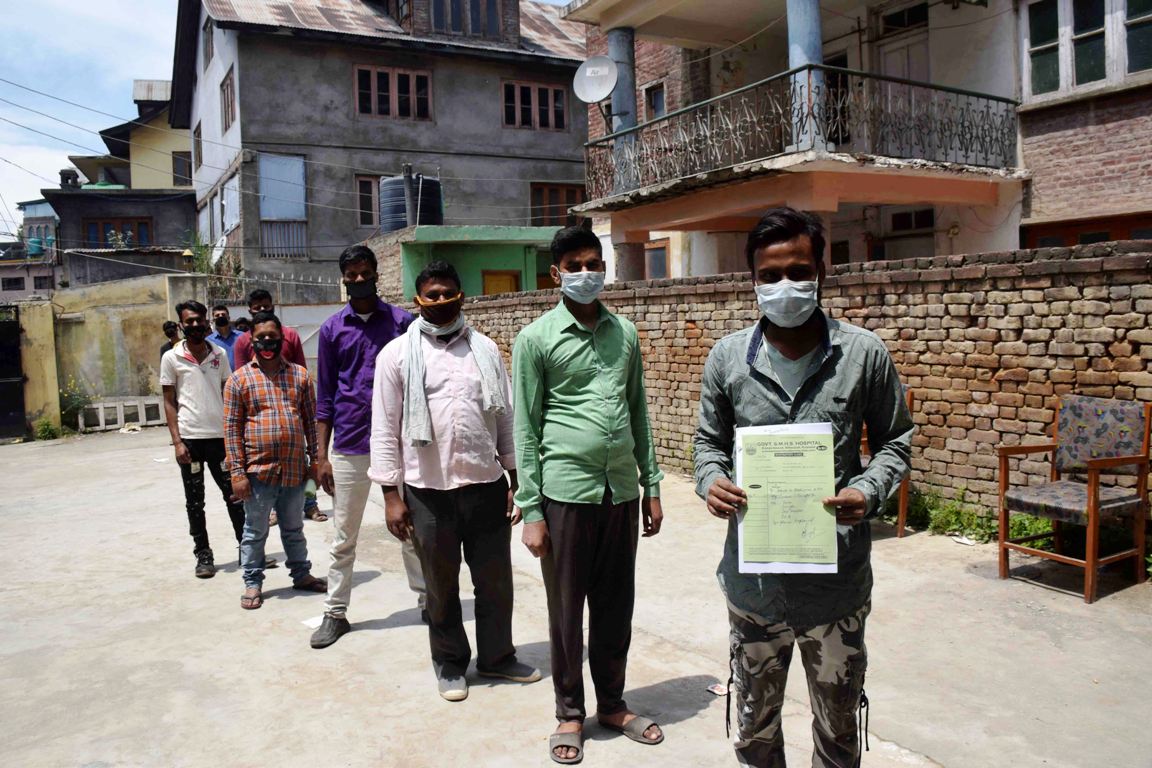

This chain of events has frightened the non-locals working in Kashmir at a time when even the natives are frustrated over the happenings. As authorities detained many hundred people while investigating the cases of these civilian deaths, new tensions were added to a society already in a panic. Quickly, the authorities stopped discouraging people from leaving and instead attempted to drive some of them to special security zones for the time being. Now, all the settlements with non-local presence will have drone surveillance.

Stayed Put

These incidents came at a time when part of the workforce would routinely leave home. The security issues actually added more people to these desperate crowds.

There are countless non-locals who have stayed put. Rajesh Kumar, an expert in Plaster of Paris (POP) work operates from Baramulla. Admitting that though there is a threat perception but it is not high enough for him to leave. Kumar has been working in Kashmir since 2015. The day when three labourers were attacked in Kulgam’s Ganjipora, Kumar was doing interiors of a shop undergoing renovation. When he heard about the attack, he switched off his phone for three days and locked himself in his rented accommodation.

However, with some assurances of people that he knew, he resumed his work and has been continuing to do so.

“I was scared initially after the attacks took place,” Kumar said. “But I decided not to leave. The people here are good. I will leave once our working season here is over.”

However, he has taken his own precautions. He does not venture outside after dusk and prefers to remain at his accommodation.

Impressive Relationship

This is not the first time that the workforce is leaving in panic. There have been attacks earlier as well. In October 2019, a few months after the reading down of Article 370, six migrant workers were killed in South Kashmir. The slain was busy in apple harvest and their killings at that time caused disruption to Kashmir’s key economy.

At the same time, there are countless instances of support and care that they got when a dangerous situation emerged for reasons of weather, health or the situation. These illustrious instances of care were on display during Covid19 lockdown, in the aftermath of reading down of Article 370, in the unrests of 2008, 2010 and 2016 and during the devastating floods of September 2014.

Muni, a carpenter from Bihar witnessed all the ups and downs Kashmir valley has gone through in recent memory. His rented room at Nowgam in the city outskirts was submerged in the 2014 floods when he was rescued and given shelter and food by the hosts nearby.

Muni said that he has never felt like an outsider in Kashmir. During August 2019, and the subsequent pandemic induced lockdown, Muni received ration and other supplies on time.

“I have always felt safe here. People of Kashmir have been very friendly all along,” Muni said. “One or two incidents cannot be generalized.”

Nasrullah, also from Bihar is also not going home. He also shares similar thoughts as that of Muni. Nasrullah works in Kashmir along with his younger brother Ameeruddin for many years now.

“We have always felt safe. We are treated by Kashmiris as their own and accorded a lot of respect,” Nasrullah said. “We don’t see any reason to leave.”

Custodians

One of the landlords who rent out his rooms to the non-locals said, it is his duty to assure them of their safety.

“We didn’t let anyone do any harm to them in the previous years and we wouldn’t let that now,” the landlord, who wishes to remain anonymous, said. “We have always ensured that they get all the supplies, ration and other daily needs, accommodation etc. It is not because we are Kashmiris but simply it is a basic human trait.”

It was this relationship that distinguished Kashmir at the peak of 2020-Covid19 lockdown when tens of thousands of labour force went home on foot takes months to reach home. During those days, special camps were held within and outside Srinagar to ensure all the basic facilities to the workforce so that they do not feel neglected. It created instances that part of the labour force that exited India’s metropolitan network would come to Kashmir, sometimes illegally.

Dubai of India

For most migrant workers, Kashmir is an attractive prospect. Though there has not been a proper survey, a smart estimation suggests that around half a million non-locals make their livelihood in Kashmir on a seasonal basis. Of them around one-fifth actually never goes home and live year-round the year.

While the typical demand-supply chain is believed to be the basic, the fact is that Kashmir offers more value to them in comparison to other places. The weather is good and the wages are considerably higher. Right now, the daily wages for a 9 am – 5 pm day are around Rs 700 and in the skilled category, these can go up to Rs 1000, depending on who works where. Right now, the daily wages for non-native workers in apple-plucking has already reached Rs 900 in south Kashmir. These wages are more than two times higher than plains in mainland India.

Coupled with low costs of living, margins in working in Kashmir are better. In Srinagar, the workforce is served tea and bread twice a day. In the periphery, especially in the apple-belts, they are being served both meals, and in most of the cases retained at home. However, most of the workforce in the Kashmir periphery is from Pir Panchal valley while the migrant labour from Punjab, UP, Bihar, West Bengal and Rajasthan mostly takes care of the urban constructions sector.

This is in addition to thousands of highly skilled workforce in the manufacturing sector, certain handicrafts, tailoring and hairstyling. Most of the brick-kilns are managed by non-local skilled labour, who mostly move with their families to the sites in Kashmir. Though the season is about to conclude, there are still a few weeks for work. A number of workers who decided against moving out admitted that they have to make a decision between sleeping hungry at home and working with dignity in Kashmir.

Economic Costs

Nevertheless, the killing of the non-local workers comes at a time when harvesting is at its peak. Most of the labour force has fled, and orchardists are facing difficulties in finding their replacement.

With the harvesting season at its peak – especially in south Kashmir, the exit of the workforce takes away much-needed labour required right now. The adverse weather forecasts have already triggered a massive rise in wages as panicky growers want to harvest well before a light snowfall impacts the produce.

Kashmir’s apple and allied fruits is a cumulative Rs 10,000 crore economy. With more than twenty million tons of yearly produce, Kashmir is India’s main apple basket. In south Kashmir, almost two-third of apple is still on trees.

“The season is at its peak. I wanted to harvest my apple produce but I cannot find any labourers. It feels like all of them have gone,” said Ghulam Nabi, who owns an orchard in Langate, down north.

Not Workers Alone

Mudasir Ahmad, the President of Sopore Fruit Mandi’s said that almost half of the non-local buyers have also left Kashmir and headed back to the plains. With harvesting season at its peak, he said that many used to leave after Diwali while others used to camp here till January.

“The buyers used to camp here for procuring fruit till January. Our money is stuck with them while some of their money is with us,” Mudasir said. “This is the peak season but unfortunately more than 50 per cent have left.”

Mudasir said that there used to be 400-450 buyers at Sopore Mandi alone. Now only 100-120 buyers remain, and they are those who have been coming here for the last 20 years. On a normal business day, he said that 200 trucks carrying more than 200 thousand boxes would leave for about 450 mandis spread across India. Some would also leave for Nepal and Bangladesh also.

“Even some Nepali and Bangladeshi buyers who used to come here have left. The market has been down by Rs 400 per box since,” he added.

One of the buyers who decided to stay is Nazeer from Bihar. Although he had concerns about his safety, he decided to stay after he got assurances from the locals and from the Sopore Fruit Mandi President himself.

“I would be lying if I say that I do not feel scared,” Nazeer said. “I do, but seeing locals comforting you is reassuring. But I have become paranoid ever since. When we sleep, even a slight noise forces us to wake up and our heart starts pounding.”

Money is another motivation for Nazeer to stay. He said this is the peak season for him to earn money. He must make as much money as he can during this season.

Construction Sector

Despite all the adverse contributions over the last few years, Kashmir continues to have a booming construction sector. The construction works, whether public or private, are going on on a massive scale. For the majority of these works, the workforce, skilled as well unskilled, is mainly drawn from among the non-locals.

The exit of non-locals from Kashmir could impact the construction and other developmental works, ranging from the construction of bridges and flyovers to new residential buildings.

Since the labour market in Kashmir is overwhelmingly controlled by the outside labour force, the new situation can create an imbalance in the labour market. By all estimates, there are only 30-40 days still left in the season. The labour work has already gone costlier.

Farooq Ahmad Dar, president of the All Jammu and Kashmir Contractors Coordination Committee, said that they hired nearly 80 per cent of their labour force from non-locals. Rest of the labour used to be Kashmiris. Now that they have gone, most of the developmental projects run the risk of being delayed, if not halted.

“We expect nearly 70 per cent of work to stop,” Dar said. “We fear funds might lapse. And its impact might be felt on the budget allocation in the next fiscal year.”

Brick Kilns

Another important sector that could face the brunt is the brick industry. Brick kilns mostly employ non-local labourers. They are the bedrock of the local brick industry. However, with them having fled, it is expected that the brick prices would also shoot up.

During the first wave of Covid-19 in India, in March 2020, when the lockdown was imposed, the prices of bricks had shot up considerably.

Haji Rajab, a brick kiln owner, said that all his labour has fled. “They are not willing to come back and this will have a direct bearing on the prices,” Haji said.

Another brick kiln owner said that the police want us to give these people security, indirectly holding us responsible if something untoward happens. “How can we guarantee all these things when we can’t guarantee our own safety,” he asked.

The construction material has already become costly post the reading down of Article 370 in August 2019. The sand and boulder mining contracts were mostly bagged by outsiders following which the prices spiked.

Political Cost

The exit of no locals has political costs also. It has exposed the security narrative that everything was all right in Kashmir. The government’s inability to guarantee safety to these people has punctured their claims of having brought an end to the militancy in the region.

The central government has been claiming that it was able to throttle militancy with the reading down of Article 370. They read their narrative in the fall of incidents of stone-throwing and militant attacks and the gradual increase in visitor footfalls as a direct consequence of the August 5 decision.

A Conspiracy?

Farooq Abdullah, a five-time Chief of Jammu and Kashmir, termed these attacks as a conspiracy to defame Kashmiris. “These killings are unfortunate and done under a conspiracy. Kashmiris are not involved in these killings. It is an attempt to defame Kashmiris,” Dr Abdullah said.

Lt Governor, Manoj Sinha on the other hand vowed to avenge the killings, adding that “security forces would give a befitting reply.”

These killings, however, have gradually become an issue in various states outside Jammu and Kashmir. Bihar’s former Chief Minister, Jitin Ram Manjhi while lashing out at the killings tweeted that if the situation in Kashmir cannot be changed, then Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Amit Shah should hand over Kashmir to Biharis. “They would improve the situation in 15 days,” he said.

Interestingly, he did not know that Bihar has a major presence in the Jammu and Kashmir administration in civil and police administration.

Security Situation

In the aftermath of these civilian attacks, police launched a massive crackdown and have reportedly detained more than 900 people. Though nobody has been formally charged, most of these people have been either kept at police stations or are shuttling between home and the investigators. This was despite the fact that police have said they killed a number of militants who were involved in these killings.

Coupled with the arrival of the Home Minister, Amit Shah, on his maiden post-2019 visit, the entire security grid is tenter-hooks. The frisking of civilians has increased across Kashmir, with a heightened security presence visible on the roads. Overnight, security bunkers have been set up throughout the city in the same manner as was being done in the early nineties. Another fall out of the attack has been that two-wheelers are being seized by the police.

As a consequence, apart from the inconvenience that is caused to the general public due to the seizure of their two-wheelers, the livelihood of delivery boys whose work depends on their bikes is impacted.

Sami Ullah, co-founder of the Fast Beetle, a valley-based specialised delivery service startup recognized under the Government of India while voicing his concerns on Twitter wrote, “Our operations continue to be at a halt due to incessant seizing of our delivery bikes in the city. Just when the businesses in Kashmir were trying to recover from the losses caused during article 370 and global pandemic, our law and order is crumbling us again and again (sic).”

“More than 500 delivery executives are making their livelihoods from the delivery jobs in Kashmir, where would they go now? @OfficeOfLGJanK @GreaterKashmir @KAshmirLife@Sandeep_IPS_JKP @rjnasirkashmir,” he tweeted.

Possible Repercussions

The killings of non-locals in Kashmir could also have repercussions for tens of thousands of Kashmiris living outside for business or education. In the aftermath of the Pulwama attack in the 2008 winter, Kashmiris living outside became targets of hate crimes and targeted violence from the Indian right-wing. Hundreds had to be rescued by the social groups, mostly in the north of India.

So far, the entire debate was restricted to the political class. However, an escalation could push things out of hands especially at a time when elections in UP are round the corner.